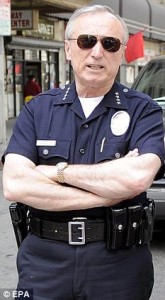

Bill Bratton, the supercop who’s credited with successfully cutting gang crime in New York and Los Angeles, is going to be consulted by the UK prime minister about how to solve the issue of the recent riots in English cities.

Bill Bratton, the supercop who’s credited with successfully cutting gang crime in New York and Los Angeles, is going to be consulted by the UK prime minister about how to solve the issue of the recent riots in English cities.

Probably without realising it, he made a very Shakespearian statement in an interview reported by the Daily Mail:

In a country that loves gardening, you fully appreciate the idea if you don’t weed a garden, that garden is going to be destroyed – the weeds are going to overrun it.

Similarly for social disorder: if you don’t deal with those minor crimes, they’re going to grow. What also grows is fear, the most destructive element in any civilised society.

Shakespeare often used the metaphor of the garden when talking about disorder and unrest. In despair at the beginning of the play, Hamlet can’t see any good in the world:

Shakespeare often used the metaphor of the garden when talking about disorder and unrest. In despair at the beginning of the play, Hamlet can’t see any good in the world:

‘Tis an unweeded garden

That grows to seed, things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

In Richard II it’s no surprise that it’s the gardeners, who come to keep the King’s garden orderly, who make the most direct link between their world and what happens in the country as a whole.

Why should we …

Keep law and form and due proportion,

Showing as in a model our firm estate,

When our sea-walled garden, the whole land,

Is full of weeds, her fairest flowers choked up,

Her fruit trees all unpruned, her hedges, ruined,

Her knots disordered, and her wholesome herbs

Swarming with caterpillars.

The ideal garden in Shakespeare’s time was a model of order, the knot garden, a formal geometrical construction. The whole point of this style of garden is that it is under control. Vigilant gardeners had to clip the box hedges regularly, scrupulously remove weeds and rake the gravel, or the garden ceased to be a garden at all, and they required so much maintenance that they can only ever have been popular with the wealthy. There are several modern examples of modern knot gardens, including the one at Nash’s House and New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon and the recently restored and controversial gardens at Kenilworth Castle. If you’d like to read more click here for an excellent description of Elizabethan gardening.

Gardens have long been used as a metaphor, mankind trying to impose order on nature in the hope this will represent society. The idea of Paradise originates from the Middle East and probably came back with the crusaders. As you say Elizabethan knott gardens were very formal and I think indicates a need to impose order on a disordered society. Ironically modern gardeners are more relaxed about weeds as they provide habitat for wildlife.

Some people like the idea of anonymity of a large city but equally think this anonymity makes them worthless, so rioting is somehow getting back at society for this lack of recognition (not to mention opportunist criminality). In a small town like Stratford it would be more difficult to get away with this as someone will know you and your family. As a boy growing up in the 1950s my mother seemed to related to half of Stratford.

Family and parentage are of course constant themes in Shakespeare’s plays, where reputation of family is much more important than today.

Interesting discussion now on the many and varied causes of the riots. It’s no surprise that they went on in cities, but the riots seem to have been often within the communities, not so much in the city centres. See this article about possible use of local libraries to help social cohesion. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/boyd-tonkin-not-one-more-library-must-close-2335952.html