When visiting other people’s houses, I always enjoy looking at their bookshelves to see what they like to read, and to keep. All my Shakespeare books are in the room where I work, while books on other favourite subjects are elsewhere in the house. Here are shelves of novels, mostly Victorian, books on gardening, art, walking guides, photography, history and the natural world. And there are two shelves of maps, mostly covering scenic areas of the UK. So it’s not surprising that I loved the British Library’s current exhibition Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands.

The exhibition’s divided into six sections: Rural Dreams, Dark Satanic Mills, Wild Places, Beyond the City, Cockney Visions and Waterlands. Within each section is a fantastic range of items from author’s first drafts, fair copies, printed books, dustjackets, and illustrated editions. Apart from giving a sense of the importance of Britainas a concept, it showcases the sheer range of the Library’s holdings combined with glorious items loaned from other collections and from living authors. It’s a tribute to the work of those organisations that collect and preserve these items. For a full review of the exhibition click here, and for a podcast, click here.

Books and manuscripts may not appear to be exciting exhibition objects, but here we have a celebration of the power of the imagination and of words, that conjure up a time, a place, or an emotion, or sometimes as with Matthew Arnold’s poem On Dover Beach, all three. Here, in pencil, biro, or the felt-tipped pen that John Lennon used for the draft of In My Life, are magical words written in notebooks or on sheets of bog-standard A4 notepaper. If only someone had collected up the contents of Shakespeare’s litter bin.

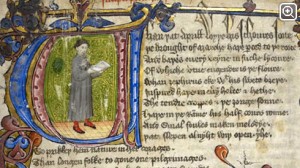

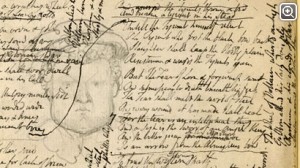

The ancient illuminated manuscripts would always have been of value. The glorious version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales has been treasured since the day it was created. But what about one of my favourite objects in the exhibition, the little notebook that originally belonged to William Blake’s brother? After his brother’s death, Blake kept the book and wrote in it for two decades, including the text of his poem The Tyger.

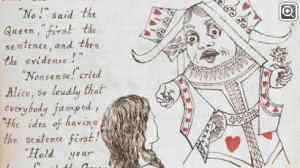

I was excited to see pages of manuscripts from some of my favourite novelists: Charles Dickens, Charlotte Bronte, Jane Austen, and of children’s books like The Wind in the Willows and Alice’s Adventures Underground. The most extraordinary ones are the first drafts of poems and novels where you see the author’s mind in action, like Stella Gibbons’ book Cold Comfort Farm, written in an unsophisticated hand, and the manuscript of Edward Thomas’s Adlestrop, voted the nation’s favourite poem. But there are surprises too: who has ever heard of Mary Collier, the eighteenth-century “washerwoman poetess”, and who would have guessed that Arthur Conan Doyle, the inventor of Sherlock Holmes, himself lived in the suburbs?

Shakespeare takes a bit of a back seat in the exhibition, though several contemporaries (Michael Drayton, Edmund Spenser, John Taylor) are represented. Although some of Shakespeare’s most memorable lines conjure up feelings of nostalgia for the loss of a rural past he rarely describes actual places. The film of Richard II screened only on Sunday treated us to sumptuous locations including St David’s Cathedral, a beach in Pembrokeshire, the garden of Packwood House in Warwickshire and several castles. Standing in for Coventry (which has changed rather a lot) was a lush green field backed by a richly wooded hillside.

The Rural Dreams section covers the rustic vision of England, already mythologised by the legends of King Arthur and represented by a manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, right up to a twentieth-century recruitment poster reminding men what they were fighting for: a landscape of green valleys and thatched cottages. Shakespeare’s Arden is represented by a single volume of the 1709 edition of his plays showing the illustration for As You Like It.

He’s there too in the Wild Places section along with those depicters of wild scenes, Thomas Hardy and the Brontes, a modern edition of King Lear illustrating the storm-beaten heath, where the savagery of the landscape mirrors the King’s mental torment.

More surprising are early reminders that industrialisation was not always seen as an evil. The mock-heroic poem The Fleece was published in 1757 by John Dyer. It celebrates the early mechanisation of rural industry, tracking the progress of wool from the farming of sheep to exporting of the cloth. Within a few decades industry had turned Britain’s landscapes into the nightmare world made notorious by writers like Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell, though George Eliot in Middlemarch optimistically welcomed the coming of the railways to rural areas.

I was fortunate to be part of a curator’s tour led by Jamie Andrews. A podcast is available from his appearance on Radio 4’s Open Book on 24 June, just follow this link.

As well as pointing out some of the gems of the exhibition he mentioned that changes in working methods means that materials like those on display are now rarely created. Instead of scratching with a pen or pencil on a piece of paper, or correct typescripts by hand, most do all the work on computers. So the exhibition also commemorates a way of working that is in decline.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of the wonderful exhibits, but I should mention the exhibition is a multi-media display containing film clips and sound recordings of readings of some items.

Entry to the exhibition is normally £9, and runs to 25 September. The British Library have offered a reader of this blog the chance to win a pair of free tickets. All you have to do is write a comment at the end of this post (subscribers should follow the link at the end of the email to The Shakespeare blog itself), about a place which you associate with a scene from one of Shakespeare’s plays. It could be a place Shakespeare mentions, or somewhere that makes you think of one of his speeches. You’ve got until Sunday 15 July, and I’m really looking forward to hearing from you!

A place which always makes me think of Shakespeare and ‘Macbeth’ is the area to the east of Inverness and, most especially Cawdor Castle. Although not the castle in which Duncan is murdered (that was Inverness, where a stone by a roundabout marks the traditional site of Duncan’s grave), Cawdor is indeed a place to which the line ‘this castle hath a pleasant seat’ truly applies, being a tall, yet beautiful, mediaeval keep , set in wonderful gardens beside a river gorge. Nearby, between Nairn and Forres is a small hill known as ‘Macbeth’s copse’ and I can never drive along that coast without thinking of the play. To give it a more personal link, my great-great-great-grandmother was Isabel Macbeth, from Nairn.

I go across Blackheath from time to time, and when I do I like to think of King Henry the Fifth in Shakespeare’s play returning victorious from France and being met there by the mayor of London and other dignitaries and a crowd of the common people who wanted him to

have borne

His bruisèd helmet and his bended sword

Before him through the city.

But King Henry ‘forbids it’ because he is ‘free from vainness and self-glorious pride’ and reckons that his victory was God’s doing alone.

I’m fond of Blackheath, the extent of it, the view over London and Canary Wharf, and its proximity to Greenwich Park and the Observatory, and the Maritime Museum down below. And now the Olympic Games are coming to the area, with equestrian events in Greenwich Park.

Returning to Shakespeare’s Henry V, I like to think too of Holinshed’s description of the mayor and the aldermen wearing scarlet and riding on horses ‘rejoicing in his return’. And what route, I wonder, would that cavalcade have taken from here into London?

It’s rather clichéd I suppose but whenever I’m on a particularly beautiful part of the coast I’m reminded of “this scepter’d isle…this fortress built by Nature for herself… this precious stone set in the silver sea….this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England”. Last year I was on the glorious Golden Cap estate in Dorset and also a little inland on the very atmospheric Eggardon Hill with its Iron Age hill fort which has one of the most spectacular views in England with the sea and Golden Cap in the distance. It’s long been one of my favourite Shakespeare speeches and seems to incorporate an essence of the longevity of English history – standing somewhere like Eggardon Hill makes me feel what a tiny part I have in that longevity.

In November 1989, I watched the last trilogy day of Adrian Noble’s production of “The Plantagenets” at the Barbican. It was the 8th time I’d seen the three of them. With the lines still ringing in my head, I made a Plantagenets pilgrimage around Yorkshire trying to get to as many of the places named in the Henry VIs plays as I could on my BritRail pass in a few days. I walked around York and imagined the three York brothers and their father, including the gruesome sight of Margaret’s sentence “Off with his head, and set it on York gates;

So York may overlook the town of York.”

Those lines were from the scene in which the Lancastrians defeated the Yorkists in the Battle of Wakefield. A short train journey away from York, I went to Wakefield and found the decrepit mounds of Sandal Castle and proceeded to utter Margaret’s speech – no doubt in some kind of imitation of Penny Downie (and which was one of my audition speeches at the time – perhaps I should revive the tradition now):

“Where are your mess of sons to back you now?

The wanton Edward, and the lusty George?

And where’s that valiant crook-back prodigy,

Dicky your boy, that with his grumbling voice

Was wont to cheer his dad in mutinies?

Or, with the rest, where is your darling Rutland?

Look, York: I stain’d this napkin with the blood

That valiant Clifford, with his rapier’s point,

Made issue from the bosom of the boy;

And if thine eyes can water for his death,

I give thee this to dry thy cheeks withal.

Alas poor York! but that I hate thee deadly,

I should lament thy miserable state.

I prithee, grieve, to make me merry, York.”

It was cold and bleak that day but Shakespeare’s lines for Margaret were invigorating but I was reliving in my mind’s eye one of the most compelling performances I have ever seen on the spot that the historical action depicted in the play actually happened. Theatre and history merging into one in Wakefield, Yorkshire.