The Welsh are rightly proud of their national history and heritage, but they haven’t always been represented seriously in literature and the media. Even in Shakespeare’s day efforts were made to set the record straight by drawing attention to the admirable qualities and culture of the inhabitants of Wales.

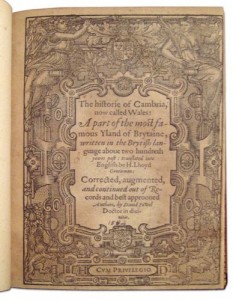

In 1584 an important book was published entitled The History of Cambria, now called Wales. The book has a complicated history. Texts detailing the history of the country back to the 7th century were collected by Caradoc, and copies of these documents were kept in a variety of places. Humphrey Lloyd, described as “a painful and a worthy searcher of British antiquities”, translated these documents into English, but on his death they were still only in manuscript. Sir Henry Sidney, father of Philip Sidney, was appointed Lord President of Wales during the 1570s and lived in LudlowCastle. To his great credit, Sidney was “desirous to have the same set out in print” and approached David Powell, his private chaplain, asking him to “peruse and correct it in such sort as it might be committed to the presse”. Powell was respected as an antiquarian and Lord Burghley allowed him privileged access to “records in the tower”, providing him with additional resources.

In his introduction to the book Powell used the opportunity, in which he must have been encouraged by Sidney, to correct the English prejudice against the Welsh. He wrote: “The inhabitants of England, favouring their countrymen and friends, reported not the best of Welshmen”.

The stereotypical Welshman was described as being proud, rebellious, fickle and unconstant. The rebellion headed by Owen Glendower which forms much of the plot of Henry IV Part 1 caused long-lasting distrust: “This hatred and disliking was so increased by the stir and rebellion of Owen Glendower, that it brought forth such greivous laws, as few Christian kings ever gave”.

At the beginning of Henry IV Part 1 Westmorland announces news from Wales. Lord Mortimer:

Against the irregular and wild Glendower –

Was by the rude hands of that Welshman taken,

A thousand of his people butchered,

Upon whose dead corpses there was such misuse,

Such beastly shameless transformation

By those Welshwomen done, as may not be

Without much shame retold or spoken of.

Powell argued though that all the Welsh were doing was defending their own land: “By what reason was it more lawful for those men to dispossess them of these countries with violence and wrong, than for them to defend and keep their own? Shall a man be charged with disobedience, because he seeketh to keep his purse from him that would rob him?”

Powell ends his introduction with a plea for a translation of “the Bible in their own language according to the godly laws already established”. Shakespeare doesn’t make jokes about the Welsh language, as he does with French in Henry V: in Henry IV Part 1 Lady Mortimer speaks and sings a song in Welsh, but Shakespeare doesn’t write an anglicised version of the language, relying on having a Welsh speaker in the company.

In his book Shakespeare and the Welsh, Frederick Harries suggests that Shakespeare dealt fairly, producing three finished portraits of Welshmen, “the soldier, the divine, and the feudal chieftain”. “In the character of Glendower we are presented with the mystical, idealistic, and the poetical side of the Celtic natures; Sir Hugh Evans is the shrewd, homely, Bible-loving Welshman; while Fluellen displays the war-like, chivalrous, and loyal attributes of the Welsh people.”

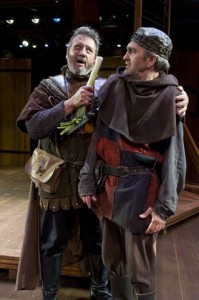

Roderick Peeples (left) as Fluellen and Will Zahrn as Pistol in the Utah Shakespeare Festival’s 2009 production of Henry V. (Photo by Karl Hugh. Copyright Utah Shakespeare Festival 2009.)

Fluellen in Henry V is my favourite among Shakespeare’s Welshmen. Although he’s sometimes a figure of fun, it’s an affectionate portrait of a man who puts duty, discipline and the rule of law first. He reminds the king of the brave history of his compatriots in the days of the Black Prince:

If your majesty is remembered of it, the Welshmen did good service in a garden when leeks did grow, wearing leeks in their Monmouth caps, which your majesty know to this hour is an honourable badge of the service…

The Welsh are renowned for their fine singing, and many distinguished actors have come from Wales, the best-known Richard Burton. There are many others, and I’ve recently heard from the Welsh actor Ian Hughes, for years a leading actor with the Royal Shakespeare Company, whose parts included Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale, the Fool in King Lear, Prince John in Henry IV and the Welsh parson Sir Hugh Evans in The Merry Wives of Windsor. Sadly he hasn’t played Fluellen, but as well as acting, Hughes has several other strings to his bow as teacher, lecturer and Business Performance Coach. He is currently developing a lecture “Shakespeare and the Story of Leadership” on the lessons contained in Shakespeare’s works. I’d be surprised if Henry V didn’t feature pretty heavily. I don’t have an online link, but if you’re interested in finding out more, let me know and I’ll forward the summaries and contact details.

Of course Burghley was a Welshman and Elizabeth’s Tudor line was Welsh. Sir Roger Williams, the great Welsh soldier who fought in the Low Countries is the basis for Fluellen and the pair share many verbal similarities. Roger Williams sardonic wit, wiles of warfare and thick Welsh accent made him a natural choice for several playwrights but it is in Henry V, first performed in 1599, that Fluellen takes to the stage as a fully formed ‘man of war’. Williams and his stage counter-part are identical, the rash bravado, impulsive action and strict adherence to military discipline are underlined by verbal similes. Williams and Fluellen speak alike, they were both born in Monmouthshire and became professional soldiers, and they have the same idiosyncratic reasoning, as Sir Sidney Lee and Dover Wilson have both pointed out.

The Welsh Jesuit, Father Hugh Owen is represented in The Merry Wives of Windsor as Father Hugh the Welshman. The poet Maurice Kyffin was at Elizabeth’s court, a student and friend of John Dee he was also a member of the literary circle that included John Harrington, Edmund Spenser, William Camden and William Morgan.

He published his magnum opus ‘Deffynniad Ffydd Eglwys Loegr’, a Welsh translation of John Jewel’s Apologia in 1595. This book was considered to be one of the greatest in the Welsh language, even though Kyffin spent very little of his life in his homeland.

I hope this is of interest,

William Corbett

Thanks for your interesting and informative comments!