The Who Invented the “Shakespearean Theatre”? conference held recently at the University of Reading ended with a round table discussion between senior academics Andrew Gurr, Stanley Wells and Reg Foakes. Over the past fifty years these three have probably written more about Shakespeare, his contemporaries, and the theatres of the time than any other trio.

The session gave them the opportunity to reflect on the issues that had been raised during the day and to talk about how the developments of the past 25 years have affected thinking about Shakespearean theatres. All began their careers before the key events of the founding of the Globe Trust and the archaeological excavations of the theatres by Museum of London Archaeology.

The type of evidence now available to theatre historians has undergone huge changes. Instead of searching for clues in the plays and sources like Henslowe’s diary at least some of their questions such as how large were the theatres and their stages, seem to have been answered by the MOLA archaeologists.

Andrew Gurr commented on the fact that the early theatres have been found to be fourteen-sided, not sixteen-sided as predicted. A fourteen-sided structure has been shown to be easy to construct using the traditional method of pole and rope.

Reg Foakes, whose work on the Elizabethan theatre goes back to the 1961 publication of Henslowe’s Diary, also talked about the size of the theatres, several of which are now known to have had a diameter of 72 feet. The Globe was built larger than the Rose, but it’s still difficult to be precise as so little of the Globe has been excavated: 85 feet is the current estimate, while the reconstructed Globe has a diameter of 102 feet. It’s now thought that the Globe was sixteen-sided, whereas it was previously thought to have eighteen sides.

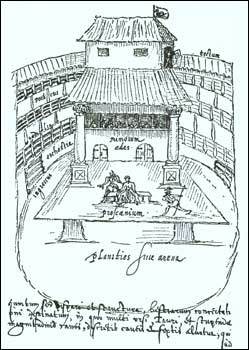

The digs have also forced a rethink about the internal arrangements of the theatres. The only evidence for this in Shakespeare’s period was the so-called “De Witt” drawing of the Swan Theatre, actually a copy made by Buchel, who did not visit it. For years this was a key piece of evidence, showing the galleried seating, the entrances, and, crucially, the shape of the stage. Reg Foakes commented that Buchel may have interpreted the drawing wrongly, and drew a theatre that was aligned more closely with what he expected to see. He commented that in the same period the gothic arches of Notre Dame in Paris were drawn as rounded Roman arches because of the fashion for Vitruvius’s book on classical architecture.

The De Witt drawing shows a rectangular thrust stage, but the archaeologists have uncovered evidence that the early stages were tapered, wider at the back than the front, and relatively shallow. The Rose stage was tapered, 30′ wide at the back, 20′ wide at the front, and 15′ deep. How, Andrew Gurr wondered, did they stage Henry VI or Tamburlaine in such a small area? Perhaps we have trouble with this because we’re used to seeing theatres built to give enough room for up to 200 extras, or we’ve grown used to seeing films using computer-generated armies going into battle, while people in Shakespeare’s time had only experienced stages erected in inn-yards or chambers, when a 30-foot wide stage might have seemed spacious.

I’m sure I don’t need to remind you of the Chorus’s first speech in Henry V when he invites us to:

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts.

Into a thousand parts divide one man

And make imaginary puissance.

In response to a question about the investigative use of the reconstructed Globe, it was agreed that although there had been a number of experiments using original practices there was much still to be done to satisfy academics in working out exactly how theatres were used in Shakespeare’s day. There had for instance not yet been an all-male production in which the female roles were taken by boys. And although the Globe stage had been adjusted by the building of catwalks, they had not experimented with altering the shape or size of the stage itself.

Stanley Wells concluded by reminding us that no matter how closely we try to revive plays as staged by Shakespeare’s company, we ourselves are not Elizabethans. Exciting as it is to see walls, pavements and finds appearing during archaeological explorations, the digs can answer only some of the questions about the players, audience and the playhouses. Finding out how the acting companies evolved, what the relationships were between Alleyn and Henslowe, and Burbage and Shakespeare, is beyond archaeology and it’s to be hoped further information will come to light. The work done on documents like the Bridewell court records analysed by Duncan Salkeld has added much to what we know about life in London during this period when the theatres were surrounded by brothels, inns and bear-baiting rings.

Archaeology is providing the key to unlocking many mysteries of the Shakespearean playhouses, but the answers to many questions are still tantalisingly undiscovered.

Sylvia.. really appreciate the fine writing and research on all your blogs. One question about this most recent. What do you mean that there had not yet been an all -male production in which female roles were taken by boys? I had thought this was standard Elizabethan theatre practice.

Thanks, Corisa

Dear Corisa,

Thanks for your comment. Apologies, I obviously haven’t expressed myself clearly! The combination of boys and men was indeed standard Elizabethan practice, but in the reconstructed Globe they haven’t put on a production with this combination of actors. I imagine the shortage of trained boys might be responsible, but it could be done with some extra training. Edward’s Boys, composed of boys at Shakespeare’s School in Stratford have staged several plays of the period with all-boy casts to great success. And of course there are many excellent child actors attending stage schools in the capital! I hope it won’t be too long before the Globe does a really authentic production.