Our fascination with the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods shows no sign of abating. Lives of the monarch and courtiers have always been recorded but in recent years it’s apparent that there is much evidence for the lives of ordinary citizens too if you look for it. The new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London, running until 5 January is significantly entitled Elizabeth 1 and her People. The exhibition focuses not only on the wearers of conspicuously expensive consumer goods like clothes and jewellery, but also on those who created them.

Our fascination with the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods shows no sign of abating. Lives of the monarch and courtiers have always been recorded but in recent years it’s apparent that there is much evidence for the lives of ordinary citizens too if you look for it. The new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London, running until 5 January is significantly entitled Elizabeth 1 and her People. The exhibition focuses not only on the wearers of conspicuously expensive consumer goods like clothes and jewellery, but also on those who created them.

The exhibition publicity claims that it “includes many outstanding paintings of Elizabeth I and her courtiers including explorers, and soldiers, and enchanting portraits of her female courtiers. Visitors will also come face-to-face with lesser-known Elizabethans including butchers, goldsmiths, brewers, merchants, writers and artists. These will be shown alongside artefacts from the period including exquisite jewellery, books and coins, which give a fascinating glimpse into their way of life.”

One notable item, that makes the link between these sumptuous paintings and everyday life is an inventory of a London haberdasher’s stock dating from 1582, an extraordinary survival held in the National Archives. The NPG’s Chief Curator Tarnya Cooper explains all in her blog post.

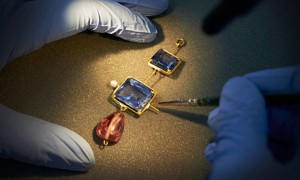

Also, at the Museum of London is another exhibition that shows off a hoard of jewels, the Cheapside Hoard, which was discovered by chance in 1912. The Guardian article explains its importance: “The hoard of almost 500 pieces was a 17th-century goldsmith’s stock – worth a king’s ransom then and priceless now…Nothing in the world comes close,” said Museum of London curator Hazel Forsyth, who has spent years studying the brooches and necklaces, rings and chains, pearls and rubies, scent bottles and fan holders, two carved gems which date back 1,300 years to Byzantium – and a watch set into a hollow carved out of one stupendous emerald which was originally the size of an apple.” Most of the jewellery dates back to the late 16th and early 17th century. The Museum’s website claims

“Through new research and state-of-the-art technology, the exhibition will showcase the wealth of insights the Hoard offers on Elizabethan and Jacobean London – as a centre of craftsmanship and conspicuous consumption, at the crossroads of the Old and New Worlds.” The exhibition The Cheapside Hoard: London’s Lost Jewels runs at the Museum of London until 27 April 2014.

Elsewhere there has been another reminder of how, in late medieval times, British embroiderers were producing some of the best work being produced. The BBC4 documentary Fabric of Britain: The Wonder of Embroidery was screened on 2 October. It’s not currently available on I-Player, though I’m including links to a clip, a piece on the Victoria and Albert Museum’s website, and an article on the subject.

Shakespeare and all theatre professionals would have needed to employ skilled craftspeople. His own father was a maker of leather gloves, and in London he chose to lodge for a while with Christopher and Marie Mountjoy, makers of elaborate and costly head-dresses whose apprentice Stephen Belott courted their daughter. His plays often call for special costumes, like the costume painted with tongues for Rumour in Henry IV Part 2, the fairies of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Prospero’s magic cloak in The Tempest.

Skilled musicians were also essential to theatre performances. I recently attended a concert entitled The Queene’s Speech, part of the Stratford on Avon Music Festival, performed by the wonderful early music group Charivari Agreable,. Their programme included instrumental music, played on treble and bass viols and virginals, poetry and song. It centred on Queen Elizabeth’s life and loves, including several well-chosen Shakespeare’s sonnets such as Sonnet 11, “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow”.

The central point of the evening was Isobel Collyer’s delivery of Elizabeth I’s great speech given at Tilbury in 1588 anticipating the attack by the Spanish Armada. Elizabeth repeatedly appeals to the people, her subjects, the source of her power. Here is the speech as it appears on the Luminarium website:

The central point of the evening was Isobel Collyer’s delivery of Elizabeth I’s great speech given at Tilbury in 1588 anticipating the attack by the Spanish Armada. Elizabeth repeatedly appeals to the people, her subjects, the source of her power. Here is the speech as it appears on the Luminarium website:

My loving people,

We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear, I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you in the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general2 shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.