Shakespeare and China was taken as the subject for this month’s meeting of the Shakespeare Club, at which the speaker was the President of the Club, Professor Michael Dobson, Head of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon.

He began by talking not about Shakespeare productions and translations in China, but about how China itself came to be represented in early versions of Shakespeare’s plays in the UK. He observed that at Hampton Court Palace in 1604, the night after a performance of “A Play of Robin Goodfellow” (perhaps A Midsummer Night’s Dream), a masque was performed that included a flying Chinese magician. This possible link with A Midsummer Night’s Dream continued with Purcell’s 1692 semi-opera The Fairy-Queen, the libretto of which is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play.

In spite of its supposed setting of Athens, Shakespeare’s play and its forest are quintessentially English, but in the first English stage depiction of China Purcell’s final scene takes the audience to a Chinese garden. It was seen as a flattering reference to Queen Mary’s famous collection of Chinese porcelain, objects which were becoming extraordinarily fashionable. And by the 1750s David Garrick counted on the popularity of China when he attempted to put on a show entitled “The Chinese Festival”.

For modern audiences, who know and love A Midsummer Night’s Dream, it’s not at all obvious why anyone would think that Shakespeare’s play might be improved by incorporating Chinese scenes and characters. But by the time of the Restoration, Shakespeare was seen as old-fashioned stuff, fit for plundering. England was becoming more European and cosmopolitan, and Shakespeare’s rustic drama was described by Pepys as “insipid and ridiculous”.

Professor Dobson, who had just returned from China, went on to talk about the history of Shakespeare in China and some current projects, in particular the Asian Shakespeare Intercultural Archive, an ambitious international project. It’s described on the website:

A S I A is a collaborative intersection between practitioners, individual scholars and three major Asian Shakespeare projects—the MIT Shakespeare Project, Relocating Intercultural Theatre (National University of Singapore) and A Web Archive of Asian Shakespeare Productions (JSPS Kaken/ Gunma-Doho Universities). A S I A is an extensive on-line archive of Asian Shakespeare productions dedicated to synergizing the field of Asian Shakespeare intercultural performance studies. This interactive, user-driven archive will feature new tools for use by scholars, teachers and audiences.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) also has a related site which contains video clips, information about major performers and companies, and commentaries as well as a catalogue of Asian Shakespeare productions. It is the brainchild of Alexander Huang who is an expert on the subject, having written the book Chinese Shakespeares.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) also has a related site which contains video clips, information about major performers and companies, and commentaries as well as a catalogue of Asian Shakespeare productions. It is the brainchild of Alexander Huang who is an expert on the subject, having written the book Chinese Shakespeares.

Alexander Huang also curated the Folger Shakespeare Library’s exhibition Imagining China in 2009-10, and material relating to the exhibition is still on the Library’s website.

Moving away from Dobson’s lecture, the Chinese real fascination with Shakespeare has resulted in a number of high-level visits of Chinese leaders to Stratford-upon-Avon.

Elsewhere, another collaborative project fronted by Stanford University, Shakespeare in China, includes information and photographs relating to five specific productions of Shakespeare in China between 1980 and 1990. The website has been created to help the “western scholar or student interested in finding out about a little-visited corner of the globalised culture of Shakespearean performance — Shakespeare in the Peoples’ Republic of China”

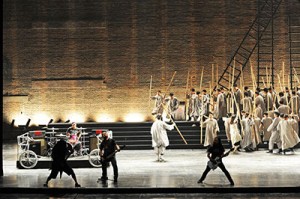

Earlier in 2013 one of the highlights of the Edinburgh International Festival was a Chinese production of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus from the Beijing People’s Art Theater.

Unusually, because it is seen as subversive in China, the production featured two of China’s most popular heavy metal bands, Miserable Faith and Suffocated. This article explains how this worked, and the following is a quotation from it:

Four thousand curious ticket holders came to see if this experiment would work. Under China’s avant-garde and often controversial director Lin Zhaohua, the pace of action was set by electric guitars and rock beats, rather than marching drums and trumpets. Pushing the boundaries, Lin used stylized heavy rock to punctuate heightened moments of conflict in the story of Coriolanus, the heroic general who joins forces with the enemy after being rejected by the “common people.”

Metal has long been germinating in China, often giving voice to a defiance of authority and expressing the teenage urge to rebel, as it does everywhere. The scene didn’t really kick off until bands such as heavy rockers Tang Dynasty and thrashers Overload ignited the scene following the bloody Tiananmen Square protests in 1989.

Shakespeare, it seems, is being embraced by both government and rebels in twenty-first century China just as it has been in so many other parts of the world.