Most of the London that Shakespeare knew disappeared in the Great Fire of London in 1666. As the city was rebuilt the original street pattern was re-established, and today we still find places with medieval names: Cheapside, Newgate, Bishopsgate and many others. But among the glossy modern buildings it’s rare to get more than a glimpse of what Shakespeare’s London was really like.

It’s not, though, completely lost as documentary evidence for the appearance of the city still exists in museums, libraries and archives. And these sources are providing information with which digital reconstructions of the City are being created using skills usually associated with video game production.

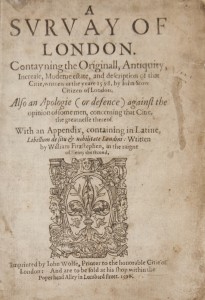

Elizabethan London was fortunate in having residents who spent their lives documenting the city’s history and appearance. One of these was John Stow, a Londoner by birth whose father had supplied churches in the pre-reformation city with lamp-oil and candles. Stow was born in 1525 and initially became a tailor. His first literary work was an edition of Chaucer but he soon became preoccupied with historical studies. His most famous work, The Survey of London, was published in 1598 after decades of research, and was so popular that it was reprinted with additions in 1603. It has since been printed dozens of times. The 1603 edition is reproduced on the website British History Online, a digital library that makes available many of the most important primary and secondary sources for the history of the UK.

The book contains information about the city’s water supply, customs and schools as well as describing the city divided into wards. Having lived through the destructiveness of the Reformation, Stow was aware of the importance of keeping a historical record.

The most important building destroyed in the Fire of London was St Paul’s, and Stow’s book contains a great deal of information about this great medieval church. The churchyard was an area Shakespeare knew well. It contained the booksellers’ stalls where he would have consulted books on offer, and where quarto editions of his own plays were sold. It was also the place where outdoor sermons were preached. Here is part of a modernised version of Stow’s description:

About the midst of this churchyard is a pulpit cross of timber mounted upon steps of stone, and covered with lead, in which are sermons preached by learned divines every Sunday, in the forenoon; the very antiquity of which cross is to me unknown. I read that, in the year 1259, King Henry III commanded a general assembly to be made at this cross… Also, in the year 1262, the same king caused to be read at Paul’s cross a bull, obtained from Pope Urban IV, as an absolution for him …This pulpit cross was by tempest of lightning and thunder defaced. Thomas Kempe, Bishop of London, new built it in form as it now standeth.

Stow’s description is brought to life by the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, based on a digital re-creation of John Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon preached in Paul’s Churchyard on 5 November 1622. The 1605 Gunpowder Plot was still a vivid memory and the subject of the sermon was the need for good citizens to be obedient to their monarch. The King asked for a copy of Donne’s sermon: this manuscript still exists and has been used in the Project.

The Project is to be officially launched at North Carolina State University on 5 November 2013, to be followed by a symposium at the University on Preaching, Performance and Public Space in Medieval and Early Modern England. The website already contains lots of material, the most exciting of which is a fly-around view of the visual model of Paul’s Churchyard and Paul’s Cross.

Here we can imagine what it might have been like to stand in and move around the Churchyard. There’s also an audio performance of the sermon, delivered by actor Ben Crystal, which has been given an audio soundscape to suggest what it might have been like to hear it within the space.

This is an exceptionally detailed and well-researched website. It includes a link to the London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage, set up to establish standards for visualisations like those for conventional publications. The preamble notes that ‘a set of principles is needed that will ensure that digital heritage visualization is, and is seen to be, at least as intellectually and technically rigorous as longer established cultural heritage research and communication methods’.

In the last week another project has been launched that provides a 3D representation of Shakespeare’s London. This too has been put together by University students, this time from De Montfort University’s Pudding Lane Productions. They have taken historic maps and engravings from the British Library and created a flythrough, with musical accompaniment, that takes the viewer along the streets of seventeenth century London. Tom Harper, curator of cartographic materials at the BL, suggests: “Some of these vistas would not look at all out of place as special effects in a Hollywood studio production” and goes on to praise their use of original materials: “I’m really pleased that the Pudding Lane team was able to repurpose some of the maps from the British Library’s amazing map collection…in such a considered way.”

Both projects make inventive use of original source material, and both illustrate the importance of cross-disciplinary work. The Pudding Lane Production site suggests the fly-through could be the foundation of another video game, but it’s also likely to be used to interest and engage students of the period.

PS Heather Knight has sent me a link to another visualisation, this time of The Theatre, the very first purpose-built theatre in London. It gives a lovely impression of being a member of the audience in this very early building. Here’s the link.