On the 10th February 1616 Shakespeare’s younger daughter Judith married a local man, Thomas Quiney. At the start of 1616 her impending marriage must have been the cause of celebration in the family. Shakespeare first saw his lawyer to draft his will in January 1616. This is often taken to mean he was already ill, but with his daughters married or betrothed it was also a good time to ensure they would be provided for.

Things started to go wrong soon after that first session with the lawyer. In the first drafting of the will, he is mentioned specifically with a bequest “vnto my sonne in L[aw]”. The marriage occurred outside the usual period for marriages (as Shakespeare’s own had been). In Shakespeare’s case it’s generally thought this was because Anne Hathaway was already pregnant. This wasn’t the case with Judith, so why was there such a hurry? Shakespeare’s marriage had been arranged by license from Worcester, but in Judith’s case no license was granted. Marrying without going through the proper procedures was frowned on, and both Judith and Thomas were excommunicated. None of this sounds like respectable behaviour, but worse was to come. Thomas might well have been in a hurry to marry Judith, because after the marriage it soon came out that he had previously had a mistress, Margaret Wheeler, who was pregnant with his child. To make matters worse, both Margaret and her baby died. Thomas was tried by the church court and sentenced to stand in front of the congregation of Holy Trinity church clad in a white sheet, for three Sundays.

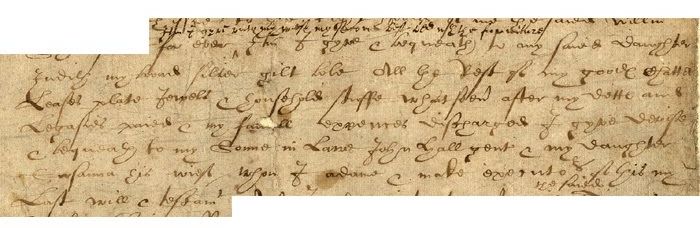

Shakespeare saw his lawyer again on 25 March. One of the significant changes is that the reference to Thomas Quiney was struck out and Judith’s name was inserted instead. Judith was to inherit £100, a cottage, and if she or her children were alive after three years a further £150 of which she should receive the interest, giving her and any children she might have an independent income. She also received Shakespeare’s “broad silver gilt bole”.

Part of Shakespeare’s will in which he mentions Susanna and John Hall who inherited most of his estate

Very little is known about Judith, but her life seems to have been full of disappointments. As far as we know she received no education, and lived in Stratford all her life. She and her twin brother Hamnet were born in 1585, but Hamnet died in August 1596. His death must have affected the whole family profoundly, not least Judith herself. This was the first of many sad events in her life, the next of which was the humiliation surrounding her marriage. She can not have been unaware of the comparison with her older sister Susanna who had already made a successful marriage to a highly-respected doctor and had a daughter. In Shakespeare’s will, it’s Susanna who inherits most of Shakespeare’s wealth including his house New Place.

Shakespeare himself died in April 1616, only a few weeks after Judith’s marriage and humiliation. In November Judith herself had a baby son, who was christened “Shakespeare”, after her father. The baby lived for only six months, dying in May 1617. Infant mortality was high, and several of Shakespeare’s own siblings had died as babies. Later, in 1618 and 1620, Judith had two more sons, Richard and Thomas. These two boys survived childhood but died within weeks of each other in 1639, aged 19 and 21, probably of plague. So Judith outlived all of her children, being buried on 9 February 1662 aged 77, while her husband died in 1662 or 1663. Thomas Quiney was by profession a vintner and tobacconist, and later became a leading member of the town’s governing council, holding its highest office, Chamberlain, in 1621 and 1622. But unlike her sister and brother-in-law who had graves in the chancel of the church, Judith and Thomas were buried in the churchyard, the site is now unknown.

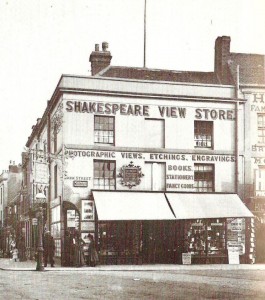

The house in which Judith and Thomas Quiney lived still stands, but unlike Susannah’s house Hall’s Croft Shakespeare’s Birthplace or the site of his grand house New Place it isn’t a museum. It used to be known as “The Cage”, and stands in the very centre of town at the junction of High Street and Bridge Street. In its time this building has been a prison, the “Shakespeare View Store”, the town’s Tourist Information Centre and now, a shop selling Crabtree and Evelyn toiletries.

In 1662 the newly-appointed vicar of Stratford, John Ward, noted in his diary his intention to visit Mrs Quiney. There’s some debate about this because it seems Judith had already died by the time he took up his post, but since Ward elsewhere noted his interest in Shakespeare it can be assumed that he had hoped to find out more about her father. This is without doubt one of the biggest lost opportunities in the history of Shakespeare biography. Judith was 31 when her father died and even at the great age of 77 would surely have had memories she could have shared. It’s just another of the factors that makes Judith Shakespeare’s story so intriguing.

Thank you Sylvia. Judith was indeed an unfortunate lady, but much of the accepted knowledge about her much-maligned husband is, in my opinion, false. The affair between Thomas and Margaret Wheeler never took place in my view. The entry in the ACTS book is a fabrication, probably made in the first half of the 20th century, as a means of ‘finding’ a reason for the changes to the will. A more likely practical reason for the changes, is that Thomas lost his case suing his wine supplier, and it was necessary and urgent, that the bailiffs could not get their hands on part of the Shakespeare estate willed to him and his wife. Shakespeare and his father before him, knew only too well the problems with bailiffs from their own experiences!

If you want to learn more about my research, I can send you a copy of my paper ‘Thos: Quiney – Gent’, which sets out my reasons for making these comments.

Dear Reg

Thank you for your unconventional view of the controversy surrounding Thomas Quiney, which I’ve never heard before. My information source is the book I’m sure you know, Shakespeare and the Bawdy Court of Stratford written by E R C Brinkworth who was a recognised authority on the Ecclesiastical Courts.

Hello Sylvia

Yes, I have a copy, and have read it from cover to cover. But, after much thought and research in the archives, (some with the help of Mairi Macdonald) I have finally reached the conclusion that the entry about Thomas Quiney is false, for a number of reasons.

Thank you Sylvia

Yes, I have a copy, and have read it from cover to cover. But,after much thought and research in the archives, (some with the help of Mairi MacDonald) I have finally reached the conclusion that the entry about Thomas Quiney is false, for a number of reasons.