The Royal Shakespeare Company has just announced its plans for the season September 2014-March 2015. In the main Royal Shakespeare Theatre a beautifully put-together programme will contribute to the commemoration of the centenary of the First World War. There will be two Shakespeare plays, Love’s Labour’s Lost and Much Ado About Nothing, and a new play by Phil Porter, The Christmas Truce. This is based around the real events of Christmas Eve 1914 when soldiers on the Western Front, both German and British, left their trenches to celebrate Christmas together. And on Christmas Day itself they played football. It’s going to illustrate how Shakespeare can be used to relate to historical events centuries after his own lifetime.

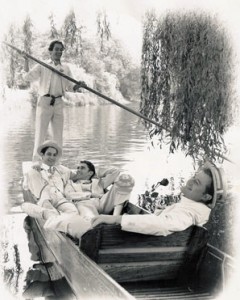

Robert Portal as Dumaine, Jeremy Northam as Berowne, Guy Henry as Longaville, Owen Teale as Navarre, RSC programme image 1993

Love’s Labour’s Lost is to be set in the summer of 1914, seen with hindsight as a golden time just before the beginning of “the war to end all wars”. This won’t be the first RSC production of the play to be set in this period. In 1993 Ian Judge directed what was often referred to as the “Brideshead Revisited” production. The programme cover showing the four young men lounging in a punt was shot on the Avon, but was intended to suggest Oxford. At the end of the play the sky darkened and the sound of distant explosions was heard in the theatre, a premonition that the elegant, witty world of the play was about to come to an unbearably violent end. Significantly, Christopher Luscombe, who is directing both the Shakespeares played Moth in this production.

Much Ado about Nothing is being set in 1920, as people are picking up their lives, broken by the war. The links between the plays are being emphasised by cross-casting so Edward Bennett plays both Berowne and Benedick and Michelle Terry plays both Rosaline and Beatrice. Booking for the public opens on 19 March, but members’ booking begins on 24 February.

Much Ado About Nothing is being billed as Love’s Labour’s Won, a mysterious play first mentioned in 1598 as an example of Shakespeare’s best work. Nobody can be sure which of Shakespeare’s plays is meant by this, or indeed if it’s a play that was lost. But Greg Doran feels the two plays belong together. In the season brochure he writes

So strong is my sense, that I am sticking my neck out to say that we have come to the conclusion that “Much Ado About Nothing” may have also been known during Shakespeare’s lifetime as “Love’s Labour’s Won”. We know Shakespeare wrote a play under this name, and scholars have debated whether this is indeed a “lost” work, or an alternative title to an existing play, just as “What You Will” is the alternative title to “Twelfth Night”. This pairing, cross-cast and with a single director Christopher Luscombe, will test out this theory.

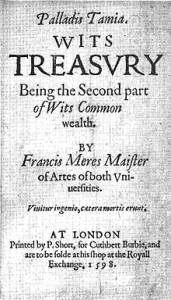

The reference to Love’s Labour’s Won came in a short section of a 700-page book by Francis Meres, Palladis Tamia: Wit’s Treasury. Being the second part of Wit’s Commonwealth. Meres had studied at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and was a student of Divinity who later went on to work as a rector and schoolmaster in Rutland. It’s a book full of comparisons taken from history and the arts that would probably have sunk without trace were it not for the famous section naming Shakespeare. This is his “Comparative discourse of our English poets, with the Greek, Latin and Italian poets”, designed to show that the culture of Elizabethan England stood comparison with the classics.

Meres’ book was published in 1598, also the year in which Shakespeare’s name appeared on the title page of one of his printed plays. It’s as if, suddenly, Shakespeare has arrived as a recognised playwright. Meres has the distinction of being the first person to praise Shakespeare unreservedly, and he coined a number of famous phrases relating to him. He speaks about his “sugar’d sonnets among his private friends”, describes him as “mellifluous and honey-tongued”, and one of “the most passionate among us to bewail and bemoan the perplexities of love”.

This passage helps confirm the dates of composition and the relative popularity of some of Shakespeare’s plays:

As Plautus and Seneca are accounted the best for comedy and tragedy among the Latins, so Shakespeare among the English is the most excellent in both kinds for the stage. For comedy, witness his Gentlemen of Verona, his Errors, his Love’s Labour’s Lost, his Love’s Labour’s Won, his Midsummer Night’s Dream, and his Merchant of Venice; for tragedy, his Richard the 2, Richard the 3, Henry the 4, King John, Titus Andronicus and his Romeo and Juliet.

With no other contemporary reference to Love’s Labour’s Won there have been several guesses as to which play it was. The Taming of the Shrew is one suggestion, All’s Well That Ends Well another, and Much Ado About Nothing. Much Ado is certainly a good fit: it’s very much a comedy, unlike All’s Well, and if anyone was to compile a list of Shakespeare’s best plays Much Ado would certainly be in there.

Is Greg Doran onto something? The only way to be sure is to see both plays, and the pairing is certain to get people talking. There’s a great opportunity to see Edward Bennett, the male lead in both plays, in action in Stratford this Sunday afternoon, 16 February, at the Shakespeare Institute. He and a number of other RSC actors past and present are doing rehearsed readings of several pieces including W S Gilbert’s Hamlet spoof Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as a charity benefit performance. If you’d like to find out more, look at the Gilbert benefit page.