Away on holiday last week, but still in touch with email and twitter, I spotted lots of Shakespeare and Stratford-related stories in the press and online. My post on the Market House coincidentally went live on the same day that a new book was published on the whole of what’s called Stratford’s Historic Spine. The spine begins at the Bridge Street end of High Street, as it happens at the Market House itself and continues along Chapel Street, Church Street and Old Town towards Holy Trinity Church. This is the route which is followed by many thousands of tourists, but in a piece for the Stratford Herald Robert Bearman suggests that the book provides “the opportunity to bring home the fact that the true value of the spine lies not just in its well-known showpiece but in the many other attractive buildings which provide the links between them.”

Away on holiday last week, but still in touch with email and twitter, I spotted lots of Shakespeare and Stratford-related stories in the press and online. My post on the Market House coincidentally went live on the same day that a new book was published on the whole of what’s called Stratford’s Historic Spine. The spine begins at the Bridge Street end of High Street, as it happens at the Market House itself and continues along Chapel Street, Church Street and Old Town towards Holy Trinity Church. This is the route which is followed by many thousands of tourists, but in a piece for the Stratford Herald Robert Bearman suggests that the book provides “the opportunity to bring home the fact that the true value of the spine lies not just in its well-known showpiece but in the many other attractive buildings which provide the links between them.”

The Stratford Society describes how ” two members of the Society, Paul Burley, retired architect and practising artist, and Bob Bearman, formerly Head of Archives at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, have spent the last three years working on a project to get the story of the Spine into book form. Paul has drawn every building along it in the form of eight continuous friezes and underneath each building Bob has provided notes of its historical and/or architectural interest.” The book is priced at £7 and can be obtained from the Society or local bookshops.

One of the most important clusters of buildings on the Historic Spine is the Guild Chapel/Guild Hall/King Edward VI School. On April 1 the school put out a lovely April Fools joke declaring that among a recently-discovered bundle of documents had been found some that mentioned Shakespeare, and indicated that he had not only been at the school (there are no records of the pupils from the time) but that he had been punished for bad behaviour several times while there. Documents had indeed been found a few weeks before, but they were all of relatively recent date. This time the aim of the good-natured jest was to draw attention to the school’s bid for funding to restore the schoolroom and Guild hall.

Forgery hasn’t always been so easy to uncover, or so well-intentioned. Back in the eighteenth century there were many people obsessed with trying to find out all they could about Shakespeare’s life. Samuel Ireland was one of these who collected all kinds of Shakespeariana, but it was his son, William Henry Ireland who in 1794 claimed to have found documents that related to Shakespeare. Former Head of Local Collections for the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Mairi Macdonald, in a piece written for the Stratford Herald back in June 2009, described the documents that included ” a sequence of legal and personal documents from the same supposed source, designed to cast Shakespeare in the light of a punctual and efficient businessman and well-regarded man of the world: a letter to the earl of Southampton (with a reply), a confession of faith proving the bard to be a good protestant, theatrical contracts, a love letter and poem to ‘Anna Hatherrewaye’ with a lock of hair (proving the poet to be an affectionate husband), and a remarkably friendly letter from Queen Elizabeth. Shakespeare’s library, with marginalia, was discovered; an original manuscript of King Lear showed that all the bawdy talk had been interpolated by actors. ”

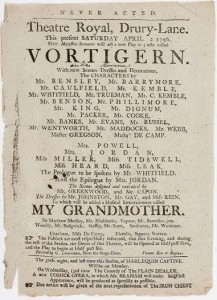

The item that provoked the most attention, though, was the manuscript of a play “Vortigern”. Last week I found this site that includes a video telling the story of this notorious play which was given a single performance at Drury Lane Theatre in 1795.

It was after this that the story of the whole manuscript discovery began to unravel, led by historian Edmund Malone. It’s easy now to scoff at the gullibility of, among others, James Boswell, but the success of many April Fools jokes reminds us that we’re easy to deceive. And how much we would all love to find a document that showed us more of Shakespeare’s life or a new play. The KES story, like that of the Charlecote poaching incident, suggest that Shakespeare was a boy of spirit, a bit like Prince Hal in the Henry IV plays, the bad boy who reformed.

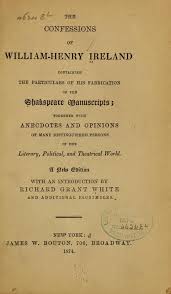

The story of William Henry Ireland is ultimately a bit sad: apparently he only began forging documents to impress his father, and after the truth came out he wrote The Confessions of William-Henry Ireland in which he explained how had created his forgeries. One method was to take an original document of the right period and write a Shakespeare signature into a gap. Ireland forgeries of this type have found their way into many major collections including that of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, and an Ireland document is in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s current exhibition Shakespeare’s the thing.