About a week ago I wrote about the extraordinary playwright, poet, prose writer and actor Thomas Heywood whose work is being investigated at the Shakespeare Institute’s Heywood Marathon. This reaches its conclusion on Saturday with Love’s Mistress, Amphrisa, the forsaken shepherdess, and A challenge for beauty. Just from these titles it’s clear that Heywood took a great interest in the virtues and roles of women in society.

Elizabeth 1 was a great inspiration. His play If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody: A play in two parts, chronicles the Queen’s life and reign only two years after her death.. It was unusual for Heywood’s plays to be printed, but perhaps an exception was made for this popular subject that ended up being reprinted many times.

His enthusiasm for Queen Elizabeth is apparent in his poem celebrating the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1613, A marriage triumph. On the nuptialls of the Prince Palatine and the Princess Elizabeth, daughter of James I. 1613. He reminds the Princess of the power of the name Elizabeth:

Could a fairer saint be shrin’d

Worthier to be divin’d?

You equall her in vertues fame

From whom you received your name.

…..

As you enjoy her name,

Likewise possess her fame;

For that alone lives after death,

So shall the name Elizabeth.

In 1631 an anonymous life of Queen Elizabeth, thought to be by Heywood, was published under the title England‘s Elizabeth, her life and troubles, that harks back to “the Greatness, Magnanimity, Constancy, Clemency, and other the incomparable Vertues of our late Queen”.

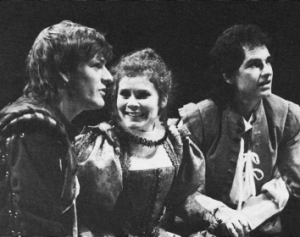

Sean Bean, Imelda Staunton and Paul Greenwood in the RSC 1986 production of The Fair Maid of the West

Heywood may never have written a character of the dramatic power of Lady Macbeth, but his women are capable of speaking for themselves and sometimes propel the action of the play in a way that Shakespeare’s women don’t. One of these is Bess Bridges, the heroine of The Fair Maid of the West, whose name is also inspired by Queen Elizabeth. Bess begins the play a lowly barmaid in a tavern, wooed by the genteel Spencer who accidentally kills a man in a brawl and flees the country. Her plight superficially resembles Juliet’s in Romeo and Juliet, but Bess refuses to stay at home and mope. After being told (wrongly) of Spencer’s death she captains a ship, setting sail to search for his body and bring it home.

I vividly remember Imelda Staunton’s funny, feisty and touching performance in the production that officially opened the RSC’s Swan Theatre in 1986. Although an adaptation of the original to which several songs were added much of Heywood’s original survived. Bess’s lover seemed to have little to do except look dashing and fight an endless stream of battles (ably done by Sean Bean who was also playing Romeo in the RST), while the plot focused on Bess’s trials and tribulations before the two were eventually reunited.

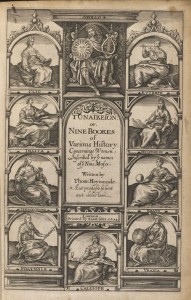

Heywood’s most extensive consideration of women comes in his major prose work,[Gynaikeion], or Nine Bookes of various History concerninge Women, inscribed by ye names of ye Nine Muses. I went to look at the original 1624 copy which is held at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. It’s a substantial and impressive volume.

Its title page sets out the book’s serious intent. The Greek God Apollo is surrounded by the nine classical muses, daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne. In Greek mythology the muses sang and danced at the festivities of the Olympians, and brought to humanity the purifying power of music, the inspiration of poetry and divine wisdom.

Each of the nine books is under the name of one of the muses, and the book tells stories of women from classical antiquity, including Greek and Roman myths, intended particularly for women to learn from. In his address to the reader, he calls the book “a collection of Histories, which touch the generalitie of women” – some with “Vertues, and Noble Actions”, some Vices”, and by women of “all Estates, Conditions, and qualities whatsoever”.

Heywood was obviously aware that such seriousness might be indigestible, so he constructs the book very much along the lines of a play: “I have…imitated our Historicall and Comicall Poets, that write to the Stage: who lest the Auditorie should be dulled with serious courses… present some Zanie… to breed in the less capable, mirth and laughter”. So there is light relief among the serious and worthy stories.

Some of these read like tabloid headlines: Of women Contentious, and Bloodie”, “Of Clamorous Women commonly called Scolds”, “Of mothers that have slaine their children, or wives their husbands”. Others illustrate women’s virtues “Of women everie way learned”, Of women poets” and some show that women could step outside their conventional roles within the home: “Of women orators, that have pleaded their own Causes”. A major section is on Witches, concluding that women “are more addicted to this divellish Art than men”.

Heywood’s book was so popular that it was plagiarised. After his death at least two books were published that lifted material straight from these pages without acknowledgement. His championing of women and issues that affect them must have touched a nerve.

Here is a full description of the magnificent title page of Gynaikeion:

Above: Apollo – God of Music and the Sun – [with a Lyre and a radiant sun]

The Nine Muses as follows:

Left:

Clio – Muse of History [with her books and a pen, a beetle on the ground in front of her]

Thalia – Muse of Comedy [smiling, with a fool’s distaff]

Terpsechore – Muse of Choral Song and Dance [ holding a lute, with a harp beside her]

Polyhymnia – Muse of Sacred Hymns [In a thoughtful pose, holding the staff entwined with snakes, traditionally associated with medicine]

Right:

Euterpe- Muse of Lyric Poetry [playing a flute, with a recorder by her side]

Melpomene – Muse of Tragedy [with a scroll, and inkhorn and books]

Erato – Muse of Erotic Poetry [with a globe, mathematical instruments and books at her feet]

Urania – Muse of Astronomy [a celestial globe on her knee and an astrolabe at her side]Below

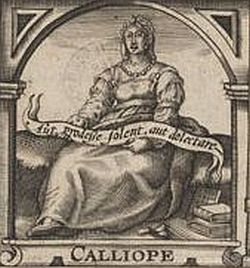

Calliope – Muse of Heroic Epic [holding the Latin verse – Aut prodesse solent aut delectare (“Let them be either of use or delight”) = the same verse as is printed below the author’s name in the title area of the page