Last time I looked at the suffrage movement in Stratford, and its connections with the Shakespeare festivals. Both in Stratford and elsewhere in the early twentieth century Shakespeare’s plays provoked discussion about the suffragette cause.

Not all of Shakespeare’s women are good role models, but in the nineteenth century many of them were seen as ideals of womanhood. Illustrations in The Graphic Gallery of Shakespeare’s Heroines, and books like Mary Cowden Clarke’s The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines (1850-52) concentrated on Shakespeare’s younger, modest heroines including Juliet, Ophelia and Miranda.

Later, it was Shakespeare’s more troubled women who became the focus of attention. In her posthumously-published lectures, Ellen Terry, who sympathised with the suffragettes, wrote “Have you ever thought how much we all, and women especially, owe to Shakespeare for his vindication of woman in his fearless, high-spirited, resolute and intelligent heroines?”

Lecturing to Shakespeare Club on 10 March, Sophie Duncan talked about some of these female characters and how the suffrage movement associated themselves with them. Here is a link to her podcast on the same subject.

Shakespeare was seen as a pillar of the establishment, enormously popular in the UK and a symbol of its values in the Empire. Being able to say that Shakespeare was on their side was a great plus for the suffragettes, struggling to be taken seriously by the political establishment.

One reason why Shakespeare’s women appealed to the suffrage movement was the strong bond of friendship that is portrayed between many of them: Rosalind and Celia, “whose loves /Are dearer than the natural bond of sisters.” Nerissa and Portia have a closer relationship with each other than with their husbands, and before they fall out even Helena and Hermia “grew together,/Like to a double cherry, seeming parted,/But yet an union in partition;/Two lovely berries moulded on one stem”. In Much Ado About Nothing the outspoken Beatrice stands up for Hero when she is wrongly accused, but needs the intervention of Benedick to challenge Claudio: “O that I were a man!”

In her essay Suffrage Critics and Political Action, Sheila Stowell documents how theatre became a focus for suffragette protests. They formed their own theatre groups, and here is a history of the Actresses Franchise League and biographies of many of its members.

In The Winter’s Tale in particular Shakespeare seemed to be firmly on the side of the suffragettes. Paulina takes matters into her own hands to preserve Hermione after she has been accused of infidelity. For the 1912 production of the play at the Savoy Theatre, directed by Harley Granville Barker, Lillah McCarthy played Hermione and Esme Beringer Paulina. All three were known suffragists, and the review in the The Suffragette noted:“the dauntless, potent, unflinching Paulina – the eternal Suffragette whom all the greatest geniuses of all ages have loved to portray. Paulina, penetrating to forbidden chambers and telling tyrants to their faces of the wronged woman and the helpless child; Paulina turning full on the unjust king the flood of her fierce eloquence, while his attendants fawn and cower for fear of his insane wrath… The real heroine of The Winter’s Tale is the woman who makes things happen – the militant Paulina, just as the real heroines of the twentieth century are the women who make things happen – the militant Suffragettes”.

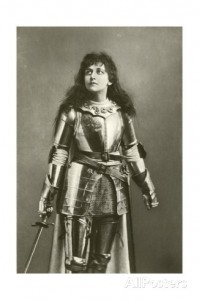

One of Shakespeare’s less popular women, Joan la Pucelle in Henry VI Part 1, became a symbol of the suffragette movement. According to Nick Walton in his blog for Blogging Shakespeare, “Joan’s clamorous voice sets Shakespeare’s play afire, and her commanding characterization made her a natural feminist icon for the women’s campaign for universal suffrage before the First World War.” Mary Kingsley, a professional actress and active suffragette, played Joan in Stratford in 1889, and a portrait was painted of her in the role at the height of suffragette activity in 1914. This photograph shows her as a warrior dressed in gleaming armour, holding a sword, her long hair flowing to her shoulders, an inspiration to other women.

Katherina, in The Taming of the Shrew, is a violent woman more difficult to reconcile with the view of Shakespeare as a supporter of votes for women. In Stratford, Constance and Frank Benson had established a long tradition of playing Kate and Petruchio. Their verbal sparring was accompanied by knockabout farce, with Kate being thrown unceremoniously over Petruchio’s shoulder and carried off stage. It was a wildly popular production performed at most of the Shakespeare Festivals. By 1912, though, changes were occurring at the Memorial Theatre and for the two performances of the play the well-like suffragist actress Violet Vanbrugh took the role of Kate. For the first performance Arthur Bourchier, Vanbrugh’s real-life husband, played Petruchio, but for the final performance of the Festival, she played the role opposite Benson himself. There’s a full account in Susan Carlson’s essay The Suffrage Shrew.

Vanbrugh’s performance was much lower in key than Constance’s, with Kate giving Petruchio no excuse for violence. Some of the critics noted that faced with this Kate, Petruchio came over as a loud-mouthed bully. It was certainly a view of the future.