At the beginning of the RSC’s current production of Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta a young man, unacknowledged in the programme, bounds on stage and reveals beneath his jacket a T-shirt bearing the logo Royal Marlowe Company in the RSC’s house style. He delivers the prologue to the play: this is Machevil, or is it Marlowe, getting his own back 400 years on? It’s a jokey start to this irreverent play and one that tells the audience not to take any of it too seriously.

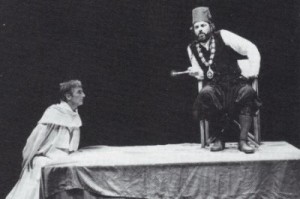

How different to the RSC’s previous production of the play on the same stage back in 1987 when the RSC veteran John Carlisle, gaunt, thin-faced and gravelly-voiced, delivered this speech, returning as the Governor of Malta who confiscates all Barabas’s goods, even his house, so the island can pay its outstanding tribute to the Turks. I don’t remember being struck by the injustices done to Barabas, only by his outrageous crimes, in particular the murder of his own daughter Abigail and her competing lovers. The play piles horror on horror until Barabas is killed by being plunged into a boiling cauldron. He dies unrepentant:

Had I but escaped this stratagem

I would have brought confusion on you all,

Damned Christian dogs, and Turkish infidels!

Alun Armstrong as Barabas turned in a fine comic performance, but I felt little sympathy with him: at the end he deserved everything he got.

The production is a reminder of how times have changed in other ways. At the beginning of the play Barabas is respectable, his only “crime” being his wealth. How far, Marlowe seems to ask, can we go in humiliating people before they fight back. The Daily Telegraph review of this production suggests that his persecution frees Barabas “from the shackles of convention and discovers what he’s made of…The production leaves it to us to decide when to part company with his amoral stratagem spree but defers that cut-off point by accentuating the way he’s part and parcel of a dirty, scheming world”.

For he that liveth in authority,

And neither gets him friends nor fills his bags,

Lives like the ass that Aesop speaketh of.

In the Guardian Charles Nicoll describes the timing of the production as “almost uncanny”. The play “seems tailor-made for more topical fears. It is a story of religious tensions and racist violence, of tangled motives and shifting sympathies, played out against the backdrop of a cynical society whose true creed is neither religion nor ideology but grasping materialist greed.. The eponymous Jew, Barabas, … Brutalised – or as we now say “radicalised” – by ill treatment, …goes on a spree of cold-blooded killings”.

Compassion, love, vain hope, and heartless fear;

Be moved at nothing; see thou pity none.

When I saw the play before, I found it uncomfortably anti-semitic, though the Jewish Chronicle noted “it is also anti-Christian and anti-Moslem. Indeed it is anti-everything except a good laugh”. In this production Jasper Britton as Barabas makes it clear we shouldn’t take what he says seriously. The much-quoted lines:

As for myself, I walk abroad o’nights,

And kill sick people groaning under walls;

Sometimes I go about and poison wells.

are spoken to test Ithamore, perhaps a challenge to see which is the tougher. The Daily Telegraph suggests Britton “has the ironic measure of the part, at times camply bored with his crimes, very much “playing” the villain”.

TS Eliot, writing around a century ago, suggested it should be seen “not as a tragedy … but as a farce”, written in a tone of “serious, even savage comic humour”. Post-holocaust, Lois Potter, writing in the Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe, asks “Is turning the play into a riotous comedy an evasion of responsibility?” It’s an awkward question, and there can be few members of the audience who have laughed at the play who feel entirely comfortable doing so. Charles Nicoll, again suggests that “Marlowe’s purpose in presenting us with this pantomime Jew is surely to satirise the crudity of the stereotype”. How appalled would the original audiences have been by it? Would the wrap-around stages on London’s first playhouses have enabled Barabas to engage his audience in the way Jasper Britton manages to do in the Swan?

Back in 1965, on the old RST stage, Eric Porter played both Shylock and Barabas in the same season, inviting comparisons between the plays. The reviewers disagree about Porter’s performance as Barabas: “subtle”, “ironic”, “intelligent”, with “a touch of hiss-the-villain burlesque”, though one reviewer complained “he does nothing to make the flesh creep”. Porter was an actor of real weight, not known for comedy. The Financial Times critic felt the whole thing was too close to farce, getting “far more laughs than Marlowe can ever have imagined”. We’ll never know what Marlowe might have imagined, but we do know, as Charles Nicoll puts it, he was “a trenchant critic of religious superstition” who bothered much less than Shakespeare did to conceal his real views. It’s hard to imagine that audiences didn’t find this savagely funny play just as entertaining as we do now. Productions of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, though, find themselves having to tread on eggshells to avoid the charge of anti-semitism. Marlowe would probably have been amused.