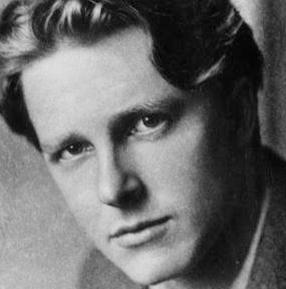

Exactly 100 years ago, on 23 April 1915, the poet Rupert Brooke died aged 27 in the Aegean en route to battle in Gallipoli. He’s often described as a World War 1 poet, but he was already an established poet destined for great things when war was declared in August 1914. He came from a privileged background, educated at Rugby School and Cambridge University. He was charming and attractive, and when he died “all England mourned the poet-soldier’s death”

Exactly 100 years ago, on 23 April 1915, the poet Rupert Brooke died aged 27 in the Aegean en route to battle in Gallipoli. He’s often described as a World War 1 poet, but he was already an established poet destined for great things when war was declared in August 1914. He came from a privileged background, educated at Rugby School and Cambridge University. He was charming and attractive, and when he died “all England mourned the poet-soldier’s death”

Brooke’s poems reflect the prevailing mood before the war. His most famous poem The Old Vicarage, Grantchester was written while abroad in 1912 and is full of yearning nostalgia for a life already past.

After the outbreak of war Brooke enlisted in the Navy, and at the end of the year he wrote a series of five sonnets about war under the title Nineteen-Fourteen. The first of these is Peace, in which Brooke suggests, as the Poetry Foundation says, “war is a welcome relief to a generation for whom life had been empty and void of meaning”. Going to war is seen as a cleansing act, with death bringing a peaceful release.

Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary,

Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love!

Oh! we, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there’s no ill, no grief, but sleep has mending,

Naught broken save this body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.

His poems have been condemned as naive, but this is more than a little unfair since he died before the awful slaughter on the battlefields of France. Again on the Poetry Foundation’s website, John Lehmann is quoted: “What soldier, who had experienced the meaningless horror and foulness of the Western Front stalemate in 1916 and 1917, could think of it as a place to greet ‘as swimmers into cleanness leaping’ or as a welcome relief ‘from a world grown old and cold and weary’?” The great poets of World War 1, including Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, are rightly revered, but they wrote after experiencing the realities of war.

It seems appropriate that Rupert Brooke died on the same day of the year as Shakespeare. Both men shared an attitude to the country for which soldiers were fighting that was romantic and nostalgic. Think of the scenes in the Gloucestershire orchard in Henry IV part 2. The fifth and most famous of the Nineteen-Fourteen sonnets is The Soldier:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

The sonnet entitled The Dead is the one that references Shakespeare most directly. Before Agincourt, Henry V declares:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

Brooke’s poem is a tribute to the ordinary soldiers who by their sacrifices have made themselves noble and brought honour to their country:

Blow out, you bugles, over the rich Dead!

There’s none of these so lonely and poor of old,

But, dying, has made us rarer gifts than gold.

These laid the world away; poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be

Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene,

That men call age; and those who would have been,

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.

Blow, bugles, blow! They brought us, for our dearth,

Holiness, lacked so long, and Love, and Pain.

Honour has come back, as a king, to earth,

And paid his subjects with a royal wage;

And Nobleness walks in our ways again;

And we have come into our heritage.

The battle of Agincourt is six hundred years ago this year, and on Saturday in Stratford-upon-Avon the celebrations for Shakespeare’s birthday are taking Agincourt as their theme, recalling this famous victory and inevitably making the link with events of 1915. On Sunday 26 April The Rupert Brooke Society will also be marking the anniversary of Brooke’s death with events in Grantchester and Cambridge.