A valuable aspect of the debate about the proposed new lifetime portrait of Shakespeare is the interest it has raised in John Gerarde’s Herball.

The previous Director of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Roger Pringle, and his wife Marian (Senior Librarian then Special Collections Librarian) built up the Trust’s already significant holdings of herbals. They reflect Shakespeare’s clear interest in gardening and plants as well as the professional expertise of his son in law Doctor John Hall, who used plants in many of his medicines. More than two dozen early herbals and books about gardening are now held in the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, including no fewer than five original copies of Gerarde’s Herball. After reading the articles by Mark Griffiths in Country Life, I went to look at some of them.*

The earliest is The Grete Herball from 1529, and although it’s in English it’s mostly a translation from the French Le Grand Herbier. Printed in Gothic or Black Letter, it’s (at least for us) difficult to read and its crude woodcuts don’t identify the plants, though the book has a lovely title page illustration showing an industrious couple harvesting their grapes while to the side Adam and Eve stand awkwardly before their banishment from Eden.

Gerarde has often been criticised for simply translating the Herbal written by Robert Dodoens. Dodoens published several books on plants and his work was made available in Dutch, French, Latin and English. The SCLA has a copy of the 1578 translation by Henry Lyte, and other books on plants from 1553, heavily annotated in Latin and English, perhaps by the Robertus Cockram who signed them in 1600. It’s interesting to see how much and for what the books were valued by their readers. Next to the entry for Wild Germander is the note that it “is good to be layd to the bytings of venemous beasts”.

The first Herbal to be written and published in England was by the Doctor of Physic, William Turner, in 1568, and dedicated to Queen Elizabeth. Turner’s book, including many illustrations, was a serious attempt to make information about plants and their uses more widely known.

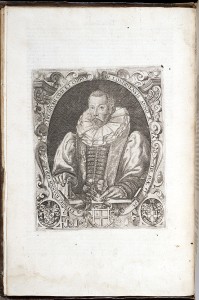

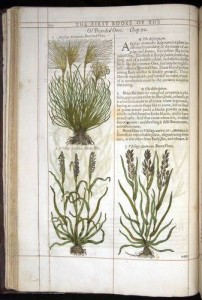

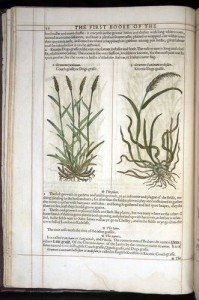

John Gerarde’s Herbal was published almost thirty years later, and in his introduction he acknowledges “that excellent Worke of Master Doctor Turner” as well as Lyte’s translation of Dodoens. But what a difference there is in the appearance of Gerarde’s book. Printed using a clear Roman font, with around 1800 high quality engravings that show what the plants look like, this book has much more immediate appeal than Turner’s. And although Gerarde may have taken details from Dodoens, his additions are readable and entertaining. For Gerarde, plants are to be enjoyed:

Talke of perfect happinesse or pleasure, and what place was so fit for that as the garden place wherein Adam was set to be the Herbarist? Whither did the Poets hunt for their sincere delights, but into the gardens of Alcinous, of Adonis, and the Orchards of the Hesperides?…Easie therefore is this treasure to be gained, and yet pretious…nothing can be confected, either delicate for the taste, dainty for smell, pleasant for sight, wholsome for body, conservative or restorative for health, but it borroweth the rellish of an herb, the savor of a flour, the colour of a leafe, the juice of a plant, or the decoction of a root.

Gerarde modestly acknowledges the book’s inaccuracies and hopes that others would improve it. And although I don’t go along with the idea that Shakespeare helped write it, there are phrases in the introduction reminiscent of his work:

Lastly my selfe, one of the least among many, have presumed to set forth unto the view of the World, the first fruits of these myne owne Labours, which if they be such as may content the Reader, I shall thinke my selfe well rewarded… The rather therefore accept this at my hands (loving Country-men) as a token of my goodwill, and I trust that the best and well minded will not rashly condemn me… But as for the slanderer or Envious I passe not for them, but return upon themselves any-thing they shall without cause either murmur in corners, or jangle in secret.

I particularly like the way that Gerarde gives as much room to weeds as to more refined garden plants. Walking last week along part of the Camel Trail in Cornwall where dozens of species of grasses and wild flowers flourish, I was reminded of Cordelia’s speech about how the mad Lear is found, crowned with the commonest of plants:

Alack, ’tis he!

Why, he was met even now

As mad as the vex’d sea, singing aloud,

Crown’d with rank fumiter and furrow weeds,

With harlocks, hemlock, nettles, cuckoo flow’rs,

Darnel, and all the idle weeds that grow

In our sustaining corn. A century send forth.

Search every acre in the high-grown field

And bring him to our eye.

*Microfiche copies are available to all readers, but access to the originals is restricted.