On Saturday 11 July 2015 it was announced that the actor and director Roger Rees had died aged 71. Better known for his more recent TV and film work in the USA, he spent many years in his early career with the Royal Shakespeare Company. I first saw him play Malcolm in the RSC’s Macbeth, then Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet at the Aldwych in 1977, but it was Trevor Nunn’s The Comedy of Errors a few weeks later that made me a real RSC convert. Roger Rees took the leading role of Antipholus of Syracuse, a performance that in his contribution to the Guardian obituary, David Edgar described as “unmatchably brilliant”.

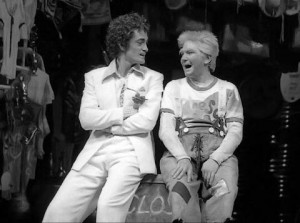

A few years later Edgar was invited to adapt Nicholas Nickleby and Rees was cast in the leading role. After a slow start, the production became a triumphant success. It remains a high point in the history of the RSC, not least because of his “electrifying” performance.

In between, though, Rees had impressed in both Shakespeare and other plays. In 1979 he had played Posthumus in Cymbeline, Semyon in Erdman’s farcical satire on Stalineque bureaucracy The Suicide and Tusenbach in Chekhov’s Three Sisters. His versatility was apparent: Michael Billington described his Posthumus as “not the usual romantic stick but a knotted junior Leontes, driven into a lather of sexual frenzy by the thought that Imogen had been false to him”, whereas in the Erdman play he was “Chaplinesque” and a “Hamlet-like ditherer in outsize jacket and Buster Keaton hat.” Then his awkward, doomed Tusenbach, hopelessly in love with Emily Richard’s Irina.

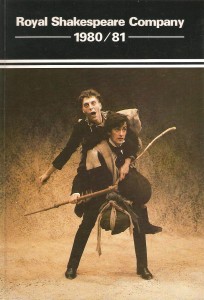

Rees could always be charming, engaging and witty in performance, but these roles increased his emotional range, and demonstrated a growing interest in psychology. Later the same year he took part in the unconventional rehearsal process for Nicholas Nickleby, an experience which affected his view of acting as collaboration. In the RSC’s 1980-81 Yearbook he described how “We started to recognise and make friends with compromise, and to understand it as a strengthening and forceful arbiter in our work.”

Edgar’s adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby allowed Rees “to chart the growth of an angry young man into a moral hero”, rescuing the part from the priggishness which Dickens’ Nicholas has been accused of. He also wrote the play with the idea that ” the actors would shift effortlessly from narrating the story to commenting on their character to playing it”. Rees proved adept at these shifts, allowing him to be both the leading actor in the play and to step outside it, addressing the audience with Dickens’ own comments. Edgar notes that Rees used this to great comic effect. In his review, James Fenton noted ” It was a good move to cast such an engaging actor in the part of young Nickleby, not because his personality closely resembles that of the Dickens hero, but because a striking character was required to add savour to the original”.

It’s hard to define Roger Rees’s on-stage personality, but those who have tried agreed on the energy of his performances. Michael Coveney, in his Obituary, calls it “vibrancy and emotional fizz”, Irving Wardle said he was “feverishly restless”, and Ros Asquith said he had “towering nervous energy”. This sounds exhausting, but Rees’s performances were also emotionally rich. James Fenton again “The nervous activity of face and limbs is evidence of an extreme attentiveness to whatever may be happening around him. Experience has taught him that all is not going to be well. Indeed, I can think of few actors who are better of conveying, through facial expressions alone, a frank acquaintance with grief.”, and Coveney defined it as “a quickness and charm that could move an audience to tears or laughter, often both, at the speed of light”.

This serious connection with the audience was used most effectively at the end of Nicholas Nickleby. The death of Smike was the heartbreaking climax of the play, but in the final moments of the production Rees encountered the curled-up body of another abandoned boy. He stooped and picked him up, and fixing the audience with a sternly challenging stare.

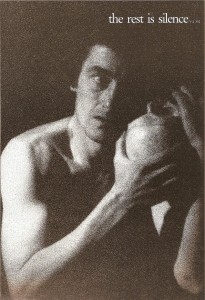

Rees’s last season with the RSC was 1984-5, when he played Berowne in Love’s Labour’s Lost and Hamlet. While making the most of the comic opportunities of Berowne, it was noted by Irving Wardle that “nothing is more memorable in the show than the sight of …Roger Rees… coming to rest among his silent companions and launching with sober passion into the great speeches on the inspiration of women, and the renunciation of artificial language”. The Hamlet was not a star vehicle but a study of troubled families. Frances Barber as Ophelia, Kenneth Branagh as Laertes and Nicholas Farrell as Horatio, each had their own weight. Meanwhile Rees gave a study in psychology: “A Hamlet who plausibly enough was in retreat from strong emotion as well as a Hamlet possessed of this actor’s air of boyish, fretful bafflement… he also brings intelligence and profound melancholy to the part” plus “mercurial quickness and sweet-souled delicacy”. “Good night, sweet prince”, indeed.