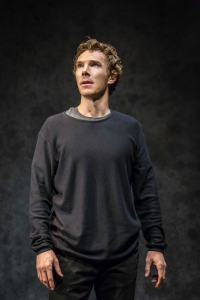

So Benedict Cumberbatch, playing Hamlet in Lyndsey Turner’s production of the play at the Barbican Theatre in London, has bowed to pressure by moving “To be or not to be” from the beginning of the play to its usual place. It’s not unusual for changes to be made in preview, but it’s a pity that a decision made for artistic reasons has been changed because of pressure from those who have seen the play before its official opening next week.

Theatre practitioners have now criticised the media for “hysteria” and “contempt”. Every comment on the play I’ve seen has focused on either the placing of this speech or on Cumberbatch’s plea for the audience not to photograph or record the live performance, which was itself shown on TV news. Nobody seems very interested in the performance itself.

As I understand it, the idea of placing the speech at the start of the play was to explain Hamlet’s state of mind at the beginning of the play, though his first soliloquy “Oh that this too too sullied flesh would melt” actually expresses his desperation and loneliness pretty fully.

Most journalists and audiences haven’t spotted the irony of the decision to move this speech around, but one of the many textual questions academics have discussed is where Shakespeare originally meant this speech to appear. In the first printed edition, the 1603 “Bad Quarto”, thought to be based on early theatrical practise, the speech appears in Act 2 Scene 2. Claudius and Gertrude have offered to pay Rosencrantz and Guildenstern for information about Hamlet, and Claudius and Polonius have also plotted to “loose” Ophelia to Hamlet while the two of them “mark the encounter” from behind an arras. With Hamlet being so comprehensively spied on, the speech shows him at his most vulnerable.

The conventional place for the speech is in Act 3 Scene 1, after Rosencrantz and Guildenstern have reported their failure to get anything out of Hamlet, and immediately before the nunnery scene with Ophelia. As well as getting the better of his old friends, Hamlet has by this time encountered the players and come up with the scheme to make Claudius give himself away by presenting on stage a scene like the murder of his father. After this, the speech about suicide seems out of place, but this is where the second Quarto, published in 1604 and thought to be a kind of official version, puts it.

In her commentary on the play in the Penguin Edition, Anne Barton commented that the Q1 placement “may well indicate stage practice in early productions. Some modern directors have found that placing the soliloquy there, at a low point in Hamlet’s despair, is more effective than it is here, just after his vigorous decision to test Claudius. The placing of the soliloquy here may indicate an afterthought – not altogether successful – influenced by the fact that including it in II.2 gives the actor a very long period on stage.”. As she suggests, sometimes these decisions are made for purely practical reasons.

Moving the speech around, and experimenting with the opening of the play, is therefore nothing new. Apparently the Lyndsey Thomas production has also toyed with the idea of Hamlet sitting on stage alone at the beginning of the play, listening to (presumably melancholy) music. In the RSC’s 1997 production, directed by Matthew Warchus, the play opened with a black and white home movie of a young boy playing with his father in the snow. Alex Jennings, as Hamlet, stood at the front of the stage holding a casket, from which he emptied his father’s ashes. The scene moved immediately to a noisy party and the court scene, at which Hamlet seemed even more out of place than usual. The whole of the first scene, in which the ghost appears, was cut so the opening of the play focused not on the avenging of a murder but on the tragedy of a son losing his father. This was a much more radical opening than the one that has been seen in London: the first scene in Hamlet is one of Shakespeare’s most dramatic opening and contains speeches which it’s thought he might have written for himself as the Ghost. This piece by Andrew Dickson looks at some of the many changes that have been made to Hamlet over the years, and asks “Does it matter?”

Collectors of Hamlets in all their variety may then be disappointed to miss this unusual and much-discussed bit of staging, but it’s likely that we’ll see it again. Now let’s hope that on the 25th the critics will concentrate on the quality of the production and the performances.