For the next four months the subject of the UK’s relationship with Europe will be at the forefront of our minds. Shortly after the Prime Minister announced that an agreement had been reached for reform to the EU, the Folger Shakespeare Library wittily posted on Twitter a map published in 1588 from Sebastian Munster’s Cosmographia, showing Europe as a woman, her head Spain and, inevitably, England and Scotland only lightly attached to the rest of the continent.

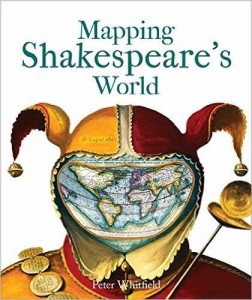

Maps that include representations of the human figure are surprisingly common. I’ve recently been enjoying Peter Whitfield’s new book Mapping Shakespeare’s World, published by the Bodleian Library in 2015. Its cover shows a map of the world enclosed inside a fool’s cap, taken from an anonymous 1590 work. As Whitfield points out, this is a reminder of the way the world descends into real madness in King Lear as we see a real fool standing before us, perhaps the sanest person on stage.

It also reminded me of the scene in King John, where the clear-sighted Bastard rails against the madness of a world governed by politicians who negotiate their rights away:

Mad world! Mad kings! Mad composition!

John, to stop Arthur’s title in the whole,

Hath willingly departed with a part.

And in the name of “commodity” they lose “all direction, purpose, course, intent”. He longs instead for “a resolved and honourable war”. The war in question is, naturally, between England and countries on the continent: France, Austria and Spain.

This image sets the tone for Whitfield’s gloriously illustrated book. It contains lots of information about how the physical world, including the cosmos, was perceived and recorded during Shakespeare’s time, but it goes much further, showing how knowledge about the world was developing and how it became a source of conflict, especially for the church. He moves on to consider the classical world, in which Shakespeare set several plays, and how ideas of Ancient Greece and Rome influenced the Elizabethans and Jacobeans.

He then moves on to look at maps of Europe from Shakespeare’s own times. Most of Shakespeare’s contemporaries would never set foot outside Britain so maps, descriptions and illustrations would have been enormously interesting. It’s hard not to be persuaded that Shakespeare must have seen some of these images: the map showing the travels of St Paul also, as Peter Whitfield indicates, includes both Ephesus and Syracuse, the outer limits of the Mediterranean explored by the family divided in The Comedy of Errors. Some of the views are stunningly beautiful: a 1500 perspective view of Venice, for instance, conveys the magnificence and mystery of this great city.

When he comes to Britain the illustrations tend to be less striking, but not always. Take the full-colour version of the title page of Michael Drayton’s great poem about England and Wales, Poly-Olbion, published in 1612. A symbolic figure of Britannia is clothed in a map and holds a horn of plenty while ships sail in the sea behind her. Around her are figures symbolising the rule and protection of the country. It’s a stunning image that can not have failed to impress people looking at it.

For Shakespeare, places are not just randomly chosen points on a map. Cymbeline is a play in which Shakespeare thinks hard about Britain’s place in a wider Europe. It’s set mostly in a fairy-tale, wild-west version of England, where it’s possible for a king’s sons to be spirited away and raised in the mountains, far from anywhere. Other scenes are set in a corrupt and sophisticated Rome. Rome demands tribute money, England refuses, and Rome attempts to invade. The Romans land and fight a battle at which they are defeated at Milford Haven (this always inspires mirth among a modern audience for whom it is known only as an oil terminal). It had never struck me, until watching a recent TV programme about Henry VII, that Shakespeare chose “this same blessed Milford” for the resolution of his play because this is where Henry VII, the ancestor of the Tudor monarchs, landed and began his campaign against Richard III. Peter Whitfield also notes this choice of locations, quoting from Camden’s Britannia:

Neither is this haven famous for the secure safeness thereof more than for the arrival therein of King Henry VII, a prince of most happy memory, who from hence gave forth unto England then hopeless, the first signal to hope well and raise itself up, when as it had now long languished in civil miseries and domestical calamities.

Cymbeline ends with the king proclaiming that for the sake of peace, England will pay the outstanding tribute and submit to Rome.

Publish we this peace

To all our subjects. Set we forward: let

A Roman, and a British ensign wave

Friendly together…

Our peace we’ll ratify: seal it with feasts.

Shakespeare picked this symbolic spot in order to remind his audience of the peace and prosperity brought about by the uniting of the country under the Tudor dynasty.

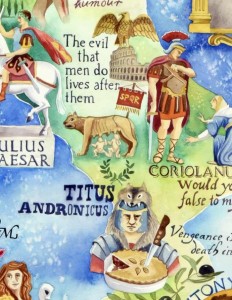

Many of the maps in Peter Whitfield’s book are things of beauty in their own right, and I wanted to finish by highlighting the work of a contemporary Oxfordshire artist Jane Tomlinson. She has created vibrantly-coloured, attractive and detailed maps of a variety of places: I like her weather map showing the Shipping Forecast areas, but she’s also painted a series of maps relating to Shakespeare. She’s done a delightfully quirky black and white map of Stratford, and more recently she’s created maps of the locations of Shakespeare’s plays, including quotations from the plays and scenes for you to spot. Following the European theme, I’ve included a detail of her map of Italy, but you can find many examples of her English maps on her website.

I love maps……four of Robert Morden’s sit proudly on my wall……they were used in later editions of Camden’s Britannia.

Perhaps Shakespeare didn’t study European maps THAT much though.

Was reading to my young one last night – The Winter’s Tale, from Lambs’ Tales. Hard to figure out how a ship from Sicily could land on the shores of Bohemia……..one of his ‘glitches’.

I don’t think Shakespeare cared for accuracy if it didn’t fit in with his dramatic vision.

I love looking at maps and it would be great to think of him being surrounded by maps.