![9781137401991[1]](https://theshakespeareblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/97811374019911.jpg) Over the past few weeks we have been remembering the battle of the Somme that began on 1 July 1916 and continued for five long and bloody months. On the first day alone 19,240 men lost their lives. Even before the start of this battle, the country, that had been at war with Germany for nearly two years must have found it difficult to celebrate anything, though in his recent essay on “Art and English Commemorations of Shakespeare”, * Alan Young notes that “Shakespeare was seen to represent the crowning glory of English culture currently under attack” He goes on to note the irony that in Germany, which Shakespeare had long been feted, there were also plans for elaborate celebrations including theatre performances.

Over the past few weeks we have been remembering the battle of the Somme that began on 1 July 1916 and continued for five long and bloody months. On the first day alone 19,240 men lost their lives. Even before the start of this battle, the country, that had been at war with Germany for nearly two years must have found it difficult to celebrate anything, though in his recent essay on “Art and English Commemorations of Shakespeare”, * Alan Young notes that “Shakespeare was seen to represent the crowning glory of English culture currently under attack” He goes on to note the irony that in Germany, which Shakespeare had long been feted, there were also plans for elaborate celebrations including theatre performances.

In England the main event was a celebratory theatre performance, a tribute to Shakespeare “humbly offered by the players, and their fellow-workers in the kindred arts of music and painting”. This was held on 2 May at Drury Lane Theatre, consisting of Julius Caesar, along with a theatrical pageant. The programme reproduced dozens of works of art “clearly designed as a celebration of British culture at its best”. It was entirely appropriate that during this event the veteran Shakespeare actor-manager Frank Benson, playing Caesar, should be knighted by the King in the Royal Box. It was arranged at the last minute: they borrowed a sword (importantly a real one, not a theatrical prop). In Benson and the Bensonians, J C Trewin described the scene: “There he knelt before the King, still with the bloodstained robes, the painted white face, the sunken eyes, the blue lips and lines of pain, and the half-bald wig of the dead Caesar. That day, lacking enough grease-paint, he had smeared the hollows of his face with dust and dirt”. The news was met, both at Drury Lane and, later in Stratford where Benson’s Company were performing A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with huge acclamation. It was an acknowledgement that theatre, even during wartime, was of significant value.

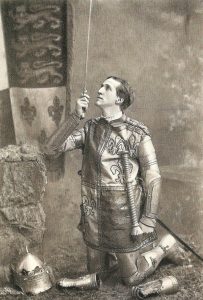

Andrew Maunder’s new book British Theatre and the Great War, published by Palgrave Macmillan, examines the role of theatre during this conflict. In his introduction he quotes the King, who praised “the handsome way in which a popular entertainment industry has helped the war with great sums of money, untiring service, and many sad sacrifices”. Events like the Tercentenary performance reinforced a sense of patriotism, but plays were also used as ways of recruiting soldiers. Henry V is always a popular play in times of war and it’s easy to see why: Henry is reassured by his advisers that war is justified, rallies his troops, and wins the day. In recent years, particularly post-Iraq, the play has been given an anti-war slant, but it would be hard not to be stirred by Henry’s speeches before and during battles. Not long after the declaration of war Benson had performed as Henry V at the Shaftesbury Theatre, and afterwards come out in front of the curtain in costume to dedicate his performance to soldiers, who he said would respond to their country’s call to arms “writing a new and magnificent history in their life’s blood”.

Andrew Maunder’s new book British Theatre and the Great War, published by Palgrave Macmillan, examines the role of theatre during this conflict. In his introduction he quotes the King, who praised “the handsome way in which a popular entertainment industry has helped the war with great sums of money, untiring service, and many sad sacrifices”. Events like the Tercentenary performance reinforced a sense of patriotism, but plays were also used as ways of recruiting soldiers. Henry V is always a popular play in times of war and it’s easy to see why: Henry is reassured by his advisers that war is justified, rallies his troops, and wins the day. In recent years, particularly post-Iraq, the play has been given an anti-war slant, but it would be hard not to be stirred by Henry’s speeches before and during battles. Not long after the declaration of war Benson had performed as Henry V at the Shaftesbury Theatre, and afterwards come out in front of the curtain in costume to dedicate his performance to soldiers, who he said would respond to their country’s call to arms “writing a new and magnificent history in their life’s blood”.

After the war, theatre was accused of being out of touch and trivial, its role in the war disregarded. Light entertainment, rather than serious stuff like Shakespeare, was all that people had wanted to see. Maunder’s book suggests that it was much more complicated than this: during World War 1 theatre was “cheerleader, propagandist and profiteer” all at the same time. In his essay in the book, Reclaiming Shakespeare 1914-1918, Anself Heinrich also begs to differ. He recalls how Benson’s performances as Henry V were used in order to recruit troops. On one occasion his performance “made so deep an impression on the audience, that some three hundred…had given their names for enlistment”. In spite of being heavily associated with the Stratford Festivals, Benson and his company spent most of their year on tour. One piece that was performed all over the country was a series of short pieces called Shakespeare’s War Cry, specially written “to stir up patriotic sentiment and reinforce his nationalist credentials”. Heinrich catalogues a whole series of places that staged Shakespeare for themselves: Edinburgh, Birmingham, Manchester, and, in Worcester an extravaganza entitled Shakespeare for Merrie England.

Actors also did their bit for the war in more practical ways. Frank Benson drove ambulances while his wife ran canteens, both in France. And companies provided entertainment to troops abroad that was far from mindless. Lena Ashwell presented Shakespeare to soldiers in Rouen, including Macbeth, Much Ado About Nothing and The Taming of the Shrew, and commented that it was “always the deeper…dramas [that drew] the largest and most appreciative audiences”.

Back in London Lilian Baylis began her focus on Shakespeare at the Old Vic in London in 1914, producing twenty-five different Shakespeare plays before the end of the war in 1918. It was said that she had taken on “the task of looking after Shakespeare”. The wartime productions of Shakespeare helped to fix the status of the Old Vic as a serious theatre with educational and patriotic aims, that ultimately led, albeit in a very roundabout way, to the foundation of the National Theatre.

Maunder’s book contains a number of terrific chapters that, as the title promises, bring new perspectives on theatre a hundred years ago.

*(In Christa Jansohn, Dieter Mehl (Eds.): Shakespeare Jubilees: 1769-2014 (Studien zur englischen Literatur, 27). Münster: LIT, 2015.