Back in July 2012 I wondered what the impact of having a young woman, Erica Whyman, as Deputy Artistic Director would be on the RSC. Earlier this week I got the chance to find out when Erica spoke to the Stratford Shakespeare Club about her role and plans for the future.

She’s been given special responsibility for new work and the redevelopment and re-opening of the RSC’s studio theatre, The Other Place, and I was particularly keen to hear what she had to say about this: like many people whose memories stretch back to the 70s or 80s (and there are quite a lot of us), I have a special place in my heart for The Other Place.

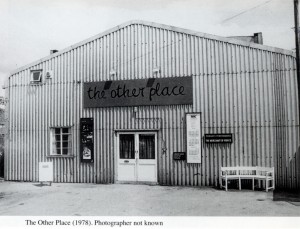

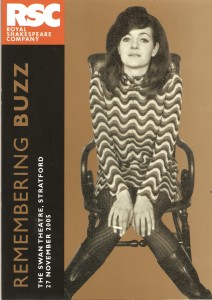

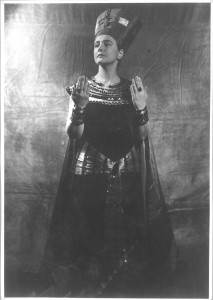

The first Other Place was a corrugated iron building that had first been erected in the 1960s as a rehearsal space. It began to be used for performances in 1973 as the Studio Theatre, but was renamed The Other Place under the leadership of Buzz Goodbody in 1974. Erica referred back to this, and to the manifesto in which Buzz set out her aims for the theatre. She had wanted this space to have a real influence on the RSC, allowing actors and directors the chance to experiment, the company to broaden the scope of their work, and new audiences to be attracted to it.

Buzz Goodbody’s manifesto was in part a political statement based on her socialist and feminist ideals. Forty years on, it’s interesting to see how another young woman defines what she sees at the function of TOP. Erica talked about good theatre: immersive, intimate, challenging, provocative, joyful. All words that could easily be applied to performances at TOP, and to the works of Shakespeare. She quoted the final scene of The Winter’s Tale: “It is required you do awake your faith”. At its most basic, and its most effective, theatre requires simply actors and an audience willing to believe in them. The original TOP had little or no budget, and neither it seems will the new theatre.

Erica Whyman calls her own aim “radical mischief”. Radical because she intends to revive the idea of using the theatre to question current events, and mischief because theatre is meant to be enjoyed, not endured. But like Buzz, she and Gregory Doran want to ask what kind of plays Shakespeare would be writing if he was here now. In the seventies Shakespeare was sometimes seen as part of the mainstream establishment, an enemy to the new. But Buzz disagreed when she wrote for the RSC Membership magazine:

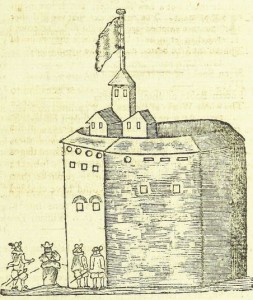

Shakespeare’s own theatre was a popular art form. Its strength and its richness derived from the social range of its audience as much as from the participants themselves. No one wants to reproduce the conditions of 1599, even if it were possible, but the challenge of closing the gap between the serious theatre and the bulk of society has to be faced.

Erica agreed: Shakespeare was a new writer, writing quickly and sometimes collaboratively. He wrote about the concerns of people of his time, but for political reasons had to disguise references to current events by setting them in the past, or in distant locations.

Buzz’s death could have dealt The Other Place a major setback, but the Artistic Director, Trevor Nunn, thought TOP’s work so important that he took personal charge. Sadly, it was her suicide that ensured her production of Hamlet got major press attention, as did subsequent work at TOP. The trademark no frills staging of The Other Place came to be often reflected on the RSC’s main stage, notably in one of the company’s triumphs, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby.

The hardships of the first Other Place were part of its charm: the first audiences had to sit on mattresses, later replaced by hard wooden seats and eventually padded benches. Some actors had to make entrances through the gents toilets, and there was no foyer, no refreshments, no reserved seating, and no showers for the actors. The repertoire included everything from Shakespeare and his contemporaries to new plays by Edward Bond, David Rudkin and Pam Gems. In 1989 after more than 15 productive years, the little hut had reached the end of its life, and was rebuilt. The 1991 auditorium was larger and more comfortable, but although still popular it was now competing with the charms of the Swan Theatre and its role seemed less well-defined. In 2006 auditorium of TOP became the foyer to the newly-built Courtyard Theatre.

Now a new Other Place is to be built within part of what is currently The Courtyard Theatre, and the best news is that during the summer of 2014 the space will be used for a short festival, and at the end of the year three plays will be staged marking the centenary of World War 1.

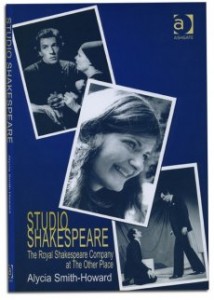

Alycia Smith-Howard’s book Studio Shakespeare gives an excellent account of the first TOP, in particular the Shakespeare productions. And in 2013 she wrote an article reassessing the subject for the online Early Modern Studies Journal in which she commented:

Artistic truth, emotional honesty, engaging audiences in acts of direct discovery, unencumbered by the proscenium or superfluous scenic detail – these are the lessons of The Other Place, lessons which are poignant and important for artists today, particularly given our current theatrical preoccupations with kitsch, gimmickry, and well-meaning gestures toward making Shakespeare more accessible. The Royal Shakespeare Company would be wise to cherish and remember the ideals of Buzz Goodbody and the ethos of The Other Place as they move forward into the next era of their history.

As Erica Whyman spoke, it seemed to me that although it’s nearly forty years since her tragic death Buzz Goodbody’s time may be about to come again.