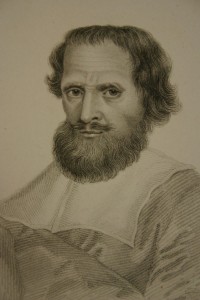

12 September 2011 is the 400th anniversary of the death of the colourful astrologer-cum-physician Simon Forman – or perhaps it was 11 September, or even 5 September, accounts vary. Whichever is correct, Forman was a well-known, even notorious figure in Shakespeare’s London, said to be the inspiration for Ben Jonson’s play The Alchemist, and a great example of the vibrancy of English life.

Simon Forman was born in 1552 in a hamlet outside Salisbury. Following a grammar school education he attempted to study at Oxford but was forced to cut short his formal education due to lack of money. He did most of his studying while working as a teacher. He was found with magical books and imprisoned, but despite his lack of training in 1592 he still managed to set himself up as an astrologer and physician in London. His casebooks, now at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, give details of 10,000 consultations. They show that he dealt with a wide range of matters, and began each consultation with an astrological reading. One common question was whether a man or his wife would die first. There’s a transcript of Forman’s formula for working this out here

Here’s an example using a fictional couple:

Mary & Jhone being man & wife which shall die first. Mary the number of her letters are 4 & the number of the letters of Jhone are 5 & Jhone is the elder & she was a mayd & he a bacheler & neyther of them was contracted to any other before, & the number of boath of the names being added togeather make 9 then because Jhone is the elder I begin with Jhone & say Jhone mary Jhone mary 9 times & the number doth end on Jhone. Therfore dico quod Jhoanna prius morietur.

The Casebook Project is currently under way to digitise and transcribe Forman’s casebooks as well as those of his follower Richard Napier, aiming to make available a huge amount of information about the preoccupations and beliefs of the people who consulted these men. Here’s a link to an article by expert Lauren Kassell about Forman and the project.

The Royal College of Physicians fined Forman for practising medicine without a licence, and in 1601 they complained that he was the worst of the “unlearned and unlawful practitioners, lurking in many corners of the City”. We’d find the methods of most of the scientists of this period hard to take seriously today. Queen Elizabeth’s astrologer, John Dee, was a famous, learned and highly regarded mathematician, but was better known for practising alchemy and being associated with the occult. Even the highly-regarded physician John Hall, Shakespeare’s son in law, prescribed alarming-sounding remedies to his patients.

It wasn’t just the workings of the human body that fascinated the Elizabethans and Jacobeans. They strove to document and explain the world around them, but were defeated by the complexity of the world that was opening up to them. Myth and fact sat side by side: Topsell’s 1607 History of Four-Footed Beasts contains information about domesticated animals like horses and goats as well as the mythical unicorn.

Forman was a compulsive record keeper, describing performances he attended at the theatre. He went to see Macbeth, and was impressed by the medical and magical elements of the play, especially the presence of a doctor making notes of Lady Macbeth’s words as she sleep-walked. You can find the full description here , but this is an extract:

In Macbeth at the Globe, 1610, the 20 of April, Saturday, there was to be observed, first, how Macbeth and Banquo, two noble men of Scotland, riding through a wood, there stood before them three women fairies or nymphs, and saluted Macbeth, saying three times unto him, “Hail, Macbeth, King of Codon; for thou shall be a King, but shall beget no kings,” etc. Then said Banquo, “what all to Macbeth, and nothing to me?” “Yes”, said the nymphs, “hail to thee, Banquo, thou shall beget kings, yet be no king”; and so they departed …

In Macbeth at the Globe, 1610, the 20 of April, Saturday, there was to be observed, first, how Macbeth and Banquo, two noble men of Scotland, riding through a wood, there stood before them three women fairies or nymphs, and saluted Macbeth, saying three times unto him, “Hail, Macbeth, King of Codon; for thou shall be a King, but shall beget no kings,” etc. Then said Banquo, “what all to Macbeth, and nothing to me?” “Yes”, said the nymphs, “hail to thee, Banquo, thou shall beget kings, yet be no king”; and so they departed …

And Macbeth…through the persuasion of his wife did that night murder the King in his own castle, being his guest; and there were many prodigies seen that night and the day before. …

Then was Macbeth crowned kings; and then he…contrived the death of Banquo…. The next night…the ghost of Banquo came and sat down in his chair behind him. And he…saw the ghost of Banquo, which fronted him so, that he fell into a great passion of fear and fury, uttering many words about his murder, by which, when they heard that Banquo was murdered, they suspected Macbeth. …

Observe also how Macbeth’s queen did rise in the night in her sleep, and walked and talked and confessed all, and the doctor noted her words.

Forman is supposed to have predicted the date of his own death, and it’s somehow appropriate that the exact date and circumstances aren’t clear. The Casebook Project should throw light on many areas of life in Shakespeare’s London.