I’ve been spending some time just recently re-reading James Shapiro’s great book 1599, which I strongly recommend if you haven’t already read it. It focuses on a single year, decisive in Shakespeare’s creative life as well being as the year when the Globe Theatre was built and opened.

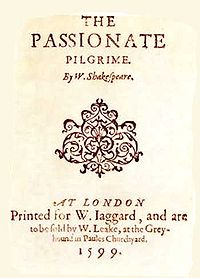

Shapiro admits that until he came to write the book he had little knowledge of one of the most successful, yet now most forgotten publications of 1599, The Passionate Pilgrim, and he’s not the only person recently to comment on this interesting little book. It gives an insight into how publication worked, and into Shakespeare’s growing standing as an author.

Shapiro admits that until he came to write the book he had little knowledge of one of the most successful, yet now most forgotten publications of 1599, The Passionate Pilgrim, and he’s not the only person recently to comment on this interesting little book. It gives an insight into how publication worked, and into Shakespeare’s growing standing as an author.

The title page of the book promises that it’s going to be a wonderful collection of poetry by that master of amorous verse, William Shakespeare. The title itself relates to those love poems for which Shakespeare was already well known, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, and to the play Romeo and Juliet. Remember Romeo and Juliet’s first meeting? Their first speeches make up a fourteen-line sonnet, in which Romeo characterises himself as a pilgrim, and Juliet joins in the game, becoming the saint to whom Romeo prays. Here are the first eight lines:

Romeo If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

Juliet Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands which pilgrims’ hands do touch

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.

The title page suggests that all the poems Shakespeare’s, but in fact only five of the twenty are by him. Two previously unpublished sonnets come first, doubtless to persuade would-be buyers to part with their cash, and the other three Shakespeare poems are those written by the lovers in Love’s Labour’s Lost. The quarto of this play had been published only the year before with Shakespeare’s name on the title page.

Even so in 1599 Shakespeare was better known as a love poet than as a writer of plays for the public playhouses. Authors had little power when it came to publication, especially with plays. He had seen the two long poems safely through the presses but this wouldn’t have been the case with the plays. Books were sold on the bookstalls in the churchyard of St Paul’s Cathedral, and The Passionate Pilgrim was sold at the sign of the Greyhound by W Leake. It must have annoyed Shakespeare. Not only was this unauthorised publication reproducing some of “his sugared sonnets among his private friends”, but his three others were intended to be laughed at as poorly-written love poems. The authors of some of the fifteen other poems have never been identified.

I recently stumbled on this fascinating blog from Adam G Hooks at the University of Iowa who examines the history of The Passionate Pilgrim and a mysterious copy that’s in their Special Collections. Do take a look.

The Passionate Pilgrim also gives us some clues about how Shakespeare wrote. The version of Sonnet 138 appears like this:

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her (though I know she lies),

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unskilful in the world’s false forgeries.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although I know my days are past the best,

I, smiling, credit her false-speaking tongue,

Outfacing faults in love with love’s ill rest.

But wherefore says my love that she is young?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O, love’s best habit is a soothing tongue,

And age (in love) loves not to have years told.

Therefore I’ll lie with love and love with me,

Since that our faults in love thus smothered be.

Shapiro points out that this is subtly, but effectively, different from how the same sonnet appeared when it was published in 1609 in another unauthorised publication.

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearned in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue:

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed.

But wherefore say she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love loves not to have years told:

Therefore I lie with her and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

It looks as if Shakespeare revised this poem between 1599 and 1609, and perhaps kept on reworking the other sonnets too over many years.