At the end of the week I’m going to the British Shakespeare Association’s Conference at Lancaster University. The three-day conference runs from 24-26 February and is on the theme of Shakespeare Inside-Out: Depth/Surface/Meaning. A host of lectures, seminars and practical sessions will be looking at the ways in which we are drawn into Shakespeare’s plays and poems through external surfaces: books, screens, images and so on, while the texts of the plays turn our deepest human experiences and emotions outwards through speech and performance. I’m really looking forward to three days of stimulating discussion on this theme, with a healthy dose of entertainment mixed in.

At the end of the week I’m going to the British Shakespeare Association’s Conference at Lancaster University. The three-day conference runs from 24-26 February and is on the theme of Shakespeare Inside-Out: Depth/Surface/Meaning. A host of lectures, seminars and practical sessions will be looking at the ways in which we are drawn into Shakespeare’s plays and poems through external surfaces: books, screens, images and so on, while the texts of the plays turn our deepest human experiences and emotions outwards through speech and performance. I’m really looking forward to three days of stimulating discussion on this theme, with a healthy dose of entertainment mixed in.

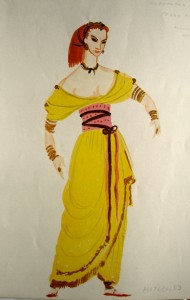

My own contribution will be a presentation looking at the subject of theatre costume design. I believe that the text of Shakespeare’s plays is fundamental to any engagement with his work, but I’m interested in how costume design can improve the audience’s understanding of the play, and how the designer uses his non-verbal responses to the characters to communicate with those involved in the production, including director and actors.

I’ve been interested in this since I saw the end of the RSC’s production of Henry IV part 2 in 1975/6. Having spent much time larking around with Falstaff in two plays, Prince Hal, Alan Howard, inherits the throne. This is the moment when he has to signal publicly that he has turned his back on his past life. It’s always a powerful moment in the play, but in this production is was electric. He appears, as Henry V, appeared far upstage, dressed from head to toe in a suit of golden metal. Even his face was covered. Walking slowly and stiffly, like a robot, he moved downstage towards Falstaff who was kneeling.

Falstaff addressed the King familiarly, as “royal Hal, and “my sweet boy”. When the king arrived downstage, he removed his mask and spoke:

Falstaff addressed the King familiarly, as “royal Hal, and “my sweet boy”. When the king arrived downstage, he removed his mask and spoke:

I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers.

How ill white hairs becomes a fool and jester!

I have long dreamt of such a kind of man…

But being awak’d I do despise my dream.

Even before he had spoken, everyone in the audience understood how completely the new king was separating himself from his past. The suit of armour also sent out signals about the state of monarchy, both repelling outside attack, and imprisoning the occupant. This costume, designed by the great designer Farrah, was a revelation to me. Up to that point, I’d always thought of costumes as complementing Shakespeare’s words, but this one was far more than mere decoration, adding an extra dimension to this key scene.

When I came to work with the RSC’s archives at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, I continued to be intrigued by the several thousand costume and set designs in the collection. The costume designer is a creative artist who has to take into account and sometimes contribute to the director’s overall concept for the production, also taking into account that the costumes have to be worn onstage by individuals who are themselves artists, and they need to be happy with the result. He has also to think about the practicalities of costume construction, collaborating with the costume department.

Jessica Risser-Milne, a costume designer, writes a blog in which she explains:

How can we as designers engage actors in an appropriate dialogue about character, when we have already created a design with the director? How do we encourage them to share and collaborate, without overriding the design choices we have already made? How can we create WITH actors (who don’t fully finalize a character until well into the rehearsal process … and for many, until they put on that costume we’ve designed for them.)?

And Jim Miller, from the University of Missouri, a practicing designer and director, explains the process in this engaging video.

You might also be interested in the RSC’s Spotlight on the Costume Department which explains the practical side of costume production.

Finally, if you’re interested in the design of Shakespeare onstage, you should look at the Designing Shakespeare website created by Christie Carson of Royal Holloway College, University of London. It covers the period 1960-2000. Just click on the Explore Collection button at the top left of the screen.