I recently visited the British Museum’s exhibition, Shakespeare: staging the World. It’s an amazing display of objects relating to the world Shakespeare knew, seen alongside video extracts of actors performing speeches from the plays, all arranged around a number of themes.

I recently visited the British Museum’s exhibition, Shakespeare: staging the World. It’s an amazing display of objects relating to the world Shakespeare knew, seen alongside video extracts of actors performing speeches from the plays, all arranged around a number of themes.

The exhibition has been widely praised in reviews, here and here, and this link leads to a series of blog posts about creating the exhibition.

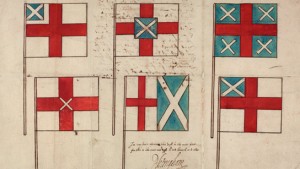

You can’t avoid the fascination with places in this exhibition. Views of London, of Venice, a pair of globes, Saxton’s map of Warwickshire, Laurence Nowell’s handy little 1564 map of England and Ireland made for William Cecil, and most impressive because of its huge size the Sheldon tapestry map of Warwickshire, made around 1588. This was one of four depicting counties in the English midlands, woven for Ralph Sheldon to hang in his house in Weston, Warwickshire. The maps specifically showed areas where Sheldon owned land.

Maps feature in a number of Shakespeare’s plays, notably King Lear and Henry IV Part 1. Nowadays maps are mostly used to get from A to B, but in Shakespeare they are to do with land ownership and management.

I’ve never been so aware before of the Shakespeare’s obsession with the idea of who controls the land and the people who live there. As well as the plays mentioned above and the other English history plays it’s a dominant theme in plays such as Hamlet, Macbeth, The Winter’s Tale and even comes into Love’s Labour’s Lost. The nature of government is discussed in Measure for Measure and Romeo and Juliet where rulers have difficulty controlling their subjects.

The exhibition makes the point that Shakespeare picks up the anxiety of the times about the effect that a change of ruler could have on the public. Monarchs had the power to control the religion and politics of the country using force. No wonder people were insecure. A recent book by Stephen Alford, The Watchers: a secret history of the reign of Elizabeth 1, looks at the subject.

But people couldn’t discuss the question that most concerned them: who would follow Elizabeth. Following the well-publicised plot to place Mary Queen of Scots on the throne the 1571 Treason Act had made it treason to discuss the question of the succession. This link takes you to a blog discussing a painting, The Allegory of the Tudor Succession which is in the exhibition.

To get round this difficulty Shakespeare and other writers set his plays in places or times remote from contemporary England, but it didn’t always work. The exhibition points out that Fulke Greville destroyed his own play on Antony and Cleopatra because the story was too reminiscent of Elizabeth’s attachment to the Earl of Essex. Shakespeare wrote his play on the subject only after the death of Elizabeth. And it also points out that although Shakespeare refers many times to England in his early plays it’s in Cymbeline, a play set in Roman times, that he repeatedly mentions Britain. The play was written after James 1’s attempts to unify Scotland and England, and to drive the point home in the First Folio the play is entitled Cymbeline, King of Britain.

In Shakespeare’s time London was not the world city is has since become, but was rapidly gaining in importance. The Folger Shakespeare Library has created some podcasts on early London, which can be downloaded here. And the British Library has just published a new book London: a history in maps.