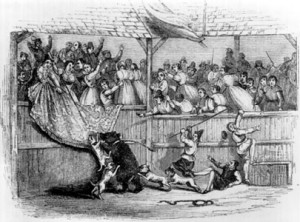

On Sunday 13 January 1583 one of the bear-baiting arenas that had stood on the Thames’s south bank collapsed. Bear-baiting was a popular spectacle for all kinds of people: both Henry VIII and Elizabeth 1 enjoyed the “sport” in which the bear was chained to a post to defend itself against the attack of mastiff dogs. Since around 1540 purpose-built arenas were put up on the south bank of London where locals and visitors could enjoy this recreation. In 1587 playhouses began to be built in the same area instead of to the north of the city.

The Reverend John Field’s account of the collapse is quoted in Julian Bowsher’s book Shakespeare’s London Theatreland. Here’s an extract:

“the yeard, standings and galleries being ful fraught, being now amidest their joilty, when the dogs and Bear were in the chiefest Batel, Lo the mighty hand of God uppon them. This gallery that was double, and compassed the yeard round about was so shaken at the foundation, that it fell (as it were in a moment) flat to the ground, without post of peere, that was left standing, so high as the stake whereunto the Beare was tied”.

Seven people were killed and many injured: Field reckons that over a thousand people were in the Bear Garden sat the time. He makes the connection with the early playhouses: “For surely it is to be feared, beesides the distruction bothe of bodye and soule, that many are brought unto, by frequenting the Theater, the Curtin and such like”. It’s ironic that the reports of the destruction of the building, as with the burning of the Globe Theatre in 1613, give us so much information about the building and what went on in it.

Although not identical, the early playhouses obviously shared similar floor plans and construction methods: perhaps when they came to build playhouses south of the river they took note and made them more robust.

Not everyone approved of animal-bating, as both Field and Phillip Stubbes thought the destruction of the arena was a punishment from God, “to show how grievously he is offended with those that spend the sabbath in such wicked exercises”.

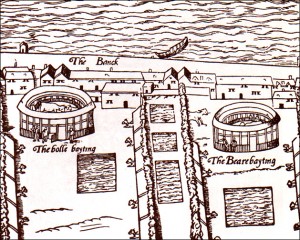

Dave Saxby of Museum of London Archaeology has made a special study of the animal-baiting arenas, and back in November gave a presentation on the subject to the University of Reading conference on Shakespearean theatres. These arenas feature on the early maps of the city, so detailed that they even show the kennels with tied up dogs as well as the ponds where the animals were washed after their bloody battles.

Dave Saxby of Museum of London Archaeology has made a special study of the animal-baiting arenas, and back in November gave a presentation on the subject to the University of Reading conference on Shakespearean theatres. These arenas feature on the early maps of the city, so detailed that they even show the kennels with tied up dogs as well as the ponds where the animals were washed after their bloody battles.

Shakespeare was fully aware of these shows. In The Merry Wives of Windsor there are a number of references, the fullest being Shallow’s attempt to chat up Anne Page by bragging: “I have seen Sackerson loose twenty times, and have taken him by the chain”. It was common for bears to be given names and they could live for many years: one list from 1638 mentions two white bears which it’s thought could be the two bear cubs from Greenland given to James 1 in 1609.

Another possible connection between Shakespeare and the animal-baiting arenas is that most famous of stage directions: “Exit, pursued by a bear”, in The Winter’s Tale. Did they bring in a real bear from the Bear Garden nearby? The audience would have been used to seeing real bears and wouldn’t have been impressed by a man in a bear skin.

There were other entertainments too: a jackanapes can be an impudent or mischievous person, especially a child, and Doctor Caius in The Merry Wives of Windsor uses the word in this sense. But the jackanapes was also a monkey on horseback chased around the arena by dogs. It was said to be “very laughable” to witness ” the screaming of the ape, beholding the curs hanging from the ears and neck of the pony”. Shakespeare knew this too: when Henry V uncomfortably tries to woo the French princess he compares himself with a jack-an-apes monkey, bound to his horse.

Like the Globe, the bear-baiting arena was quickly rebuilt after its collapse. It’s an uncomfortable thought that these brutal entertainments were competing with the performance of Shakespeare’s plays taking place close by. At the end of Macbeth, the king compares himself with a bear:

Like the Globe, the bear-baiting arena was quickly rebuilt after its collapse. It’s an uncomfortable thought that these brutal entertainments were competing with the performance of Shakespeare’s plays taking place close by. At the end of Macbeth, the king compares himself with a bear:

They have tied me to a stake; I cannot fly,

But bear-like I must fight the course.

Bear-baiting was finally banned in England in 1835, but exploiting animals for entertainment still continues. The photograph shows a dancing bear which my father photographed in Athens in 1936.

… not forgetting Fabian’s words in Twelfth Night: …’ you know he brought me out of faith with my lady about a bear baiting…’; indicating that such entertainments, as with (e.g.) football today were disapproved of as a characteristically ‘popular’ diversion- and which also, in a titular sense, links aspects of Tudor entertainment to the celebration of popular festivals.