BBC 2 is currently screening a season, Genius of Invention, accompanied by a listing of 50 Great British Inventions. But although these include the obvious (steam and jet engine) and the quirky (soda water, baby buggy), not one of these was invented before Jethro Tull’s 1701 seed drill. It was a landmark in the modernisation of agriculture: by dropping seeds at regular intervals at the right depth for optimum germination it increased crop yields eightfold, helping to increase the population and their life expectancy. And the freeing up of the agricultural population helped to set the scene for the industrial revolution.

But did British inventiveness really only start in 1701? Advances in scientific thinking are often dated back to the foundation of the Royal Society in 1660, when it became fashionable to devote one’s thinking to science. But surely, necessity had been the mother of invention, and Britons had found solutions to practical problems, before this date?

In his introduction to the magazine, Michael Mosley quotes James Dyson, the vacuum cleaner man, who believes that our inventiveness owes much to being an island race. Perhaps Jethro Tull, based in landlocked Oxfordshire, was just an exception because in the century before the foundation of the Royal Society many inventors were obsessed with all aspects of seagoing enterprise. Stephen Johnson, in his thesis, Making mathematical practice: gentlemen, practitioners and artisans in Elizabethan England (Ph.D. Cambridge, 1994), explains the pressures and opportunities: “All aspects of the industry were undergoing rapid development throughout Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. Commercially, there were the early voyages of discovery and the subsequent development of long-distance trade. Organisationally, there was the establishment of the first permanent, ocean-going navies. Technically, there were challenges such as the adoption of Mediterranean carvel construction techniques in Northern Europe and the development of 3- and 4-masted full-rigged ships. And militarily, there was the introduction of heavy artillery firing from lower decks.”

English inventors were among the best: Mathew Baker was a royal master shipwright responsible for the construction or rebuilding of many of the ships used to repel the Spanish Armada in 1588. His manuscript, known as Fragments of Ancient English Shipwrightry, explains the developments he made in the design of warships to made them less clumsy and more maneoeuverable than earlier ships.

His success is confirmed by Thomas Fuller’s comparison of Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare in his Worthies of Warwickshire, “which two I beheld like a great Spanish galleon and an English man-of-war. Master Jonson, like the former, was built far higher in learning, solid, but slow in his performances; Shakespeare, with the English man-of-war, lesser in bulk, but lighter in sailing, could turn with all tides, tack about and take advantage of all winds by the quickness of his wit and invention.”

On related subjects, William Bourne of Gravesend published a 1574 manual on navigation including tables to aid the calculation of latitude, and Christopher Saxton’s 1579 atlas covering all of England was the first national atlas to be published anywhere.

The science of astronomy suffered from often being confused with astrology. The Puritan writer Philip Stubbes condemned “astrologers, astronomers and prognosticators” who relied on “mere conjectures, supposals, likelihoods, guesses… conjunctions of signs, stars and planets, with their aspects and occurrents, and the like, and not upon any certain ground, knowledge or truth, either of God or of natural reason”. John Dee was a man of enormous learning and a brilliant mathematician, but his obsession with astrology and the search for the philosopher’s stone that would turn base metal into gold seriously damaged his reputation as a scientist.

The man who was the greatest influence on scientific thought and method was Francis Bacon, who encouraged practical applications of science, which should be “operative to the endowment and benefit of man’s life”. He called for a “spring of a progeny of inventions, which shall overcome, to some extent, and subdue our needs and miseries”.

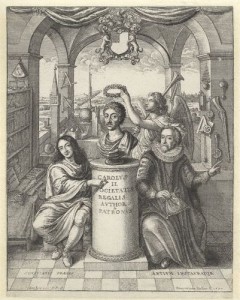

Bacon was so highly thought of that in the frontispiece to the History of the Royal Society he is pictured as one of its founding influences. His great interest in the theory and application of heat and cold was his undoing. In spring 1626 he was out driving through snow when he decided to conduct an impromptu experiment, buying and then stuffing a dead chicken with snow to find out more about the effect of cold on putrefaction. Sadly he caught a chill from which he died.

But if you’re looking for inventiveness in Shakespeare’s time you need look no further than the theatre itself. Julian Bowsher comments in his book Shakespeare’s London Theatreland “the iconic polygonal playhouses that sprang up …were unique buildings”. Roughly circular with three tiers of galleries, they were so unusual that they were commented on by many visiting foreigners. The Chorus in Henry V comments on their inadequacy, but these permanent buildings encouraged experimentation not possible when plays had to be adapted to inn yards or indoor halls. The inventiveness of the builders of the theatres literally set the scene for some of our greatest cultural achievements.

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

While it is true that the introduction of the seed drill by Jethro Tull helped the modernisation of agriculture in this country, such seed drills were by no means British inventions. They were used in China in the 3rd Century BC. and Jethro must have known this since his book ‘Horse-Hoeing Husbandry’ is copied from Chinese manuals from that time. The full story of the source in China of much of our science and technology has still to become widely known, despite Joseph Needham’s groundbreaking work ‘Science and Civilization in China’. ‘The Genius of China’ by Robert Temple is a good introduction to the subject. As Robert Temple said in 1986, “The technological world of today is a product of both East and West to an extent which until recently no one had ever imagined”. Your account of this BBC 2 Genius of Invention season makes me wonder how well we’re doing today!