Of all the times for it to happen, on the day Andy Murray won Wimbledon my broadband connection failed, finally coming back to life about half an hour after he raised that trophy. I was painfully aware, all day, of how pathetically reliant I’ve become on the technology that lets me communicate with others around the world in seconds.

Of all the times for it to happen, on the day Andy Murray won Wimbledon my broadband connection failed, finally coming back to life about half an hour after he raised that trophy. I was painfully aware, all day, of how pathetically reliant I’ve become on the technology that lets me communicate with others around the world in seconds.

The nature and speed of travel and both real and online communication has been on my mind in the last few days. I’m very much looking forward to Ben Jonson’s Walk, a virtual walk that begins on 8 July. It follows Ben Jonson’s 1618 walk from London to Edinburgh, a leisurely journey that took him until September to complete. Jonson was in no rush, taking the opportunity to visit many of his genteel friends and admirers on the way. I wrote about it a week or two ago: the people in charge of the project at the University of Edinburgh are going to be tweeting and blogging as Ben travels, and it’s going to be a great reminder of just how difficult it used to be to get news from place to place.

The theatre group Handlebards are already on the way to doing the journey in reverse. I was sent information about this wonderfully inventive tour a couple of weeks ago and am full of admiration for the all-male group who are spending the summer taking two of Shakespeare’s plays, Twelfth Night and Romeo and Juliet, on tour on their bicycles. They describe it as 4 actors, 4 bicycles, 40 characters and a 926 mile adventure. All their costumes, props, and tents are carried on the bikes with them. Take a look at their itinerary, which ends up in Chelsea on 23 August, and give them your support. This is a great idea that combines Shakespeare with caring for the environment and I’m already looking forward to seeing them perform Twelfth Night on 11 August at the Dell in Stratford-upon-Avon.

The theatre group Handlebards are already on the way to doing the journey in reverse. I was sent information about this wonderfully inventive tour a couple of weeks ago and am full of admiration for the all-male group who are spending the summer taking two of Shakespeare’s plays, Twelfth Night and Romeo and Juliet, on tour on their bicycles. They describe it as 4 actors, 4 bicycles, 40 characters and a 926 mile adventure. All their costumes, props, and tents are carried on the bikes with them. Take a look at their itinerary, which ends up in Chelsea on 23 August, and give them your support. This is a great idea that combines Shakespeare with caring for the environment and I’m already looking forward to seeing them perform Twelfth Night on 11 August at the Dell in Stratford-upon-Avon.

The plots of both Twelfth Night and Romeo and Juliet turn on the delivery of letters, especially in Romeo and Juliet where the lack of a reliable postal service means that Romeo fails to receive Friar Laurence’s letter telling him that Juliet is not really dead.

I’ve recently discovered a fascinating new website, created by the University of Glasgow, Bess of Hardwick’s letters, which bring together all the known surviving letters written by or to this formidable woman. Although modestly born around 1521, Bess made herself a powerful matriarch and the founder of a substantial dynasty. She married four times, and her husbands brought her wealth and status. She is best remembered today for building some of the most impressive stately homes of the day, especially Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. To quote the site:

I’ve recently discovered a fascinating new website, created by the University of Glasgow, Bess of Hardwick’s letters, which bring together all the known surviving letters written by or to this formidable woman. Although modestly born around 1521, Bess made herself a powerful matriarch and the founder of a substantial dynasty. She married four times, and her husbands brought her wealth and status. She is best remembered today for building some of the most impressive stately homes of the day, especially Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. To quote the site:

Bess’s letters bring to life her extraordinary story and allow us to eavesdrop on her world. The letters allow us to reposition Bess as a complex woman of her times, immersed in the literacy and textual practices of everyday life as she weaves a web of correspondence that stretches from servants, friends and family, to queens and officers of state.

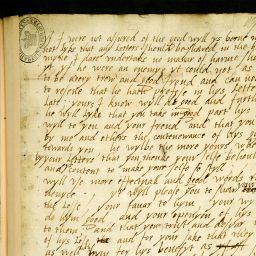

The site contains a lot more than just digitised images of the 234 letters. Many of them have been transcribed, allowing anyone to read them (though the original spelling has been retained), and they are searchable.

What I’ve particularly enjoyed though is the background information, commentaries that provide guides to the whole business of letterwriting from the preparation of paper and ink, handwriting, how letters were delivered, and the writing styles adopted by Bess herself and by those writing to her, depending on the circumstances. Many of the letters are written in what we would think a sycophantic style, but her extreme politeness and flattery obviously worked.

One of the letters, from 1573, offers guidance to an unknown recipient on how to write a persuasive letter, based on her own experience. There’s little punctuation to help, and the spelling is difficult, but you can almost hear her voice suggesting “the more earnest and plain it is the more good it will do”. She writes that the recipient of the letter

wylbe the more yours when he knows by your Letters that you thenke your selfe behoulding to hym and ys content to make your selfe so styll;/ your selfe wyll vse more effectuall and good words then I can deuyce./ … with promys that you wyll euer bethankfull to hym and hys and to requyt yt by all the good means that shall Ly in your powar, the more earnyst and playn yt ys the more good yt wyll doe.

Shakespeare was a master of persuasive writing, and it’s regrettable that we don’t have a single one of his own letters. But perhaps we’re better off with those within the plays, because Shakespeare’s letters home were probably like the one from actor Edward Alleyn to his wife from Bristol in which, instead of telling us how the plays have been going down he reminds her to dye his stockings black and to sow spinach in the garden.