When Shakespeare wanted to conjure up a sense of foreboding he often used the image of the birds of the crow family: crows, magpies, ravens and rooks. Lady Macbeth chillingly predicts the King’s murder:

The raven himself is hoarse

That croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan

Under my battlements.

And at the beginning of the play scene in Hamlet, the prince links the idea of revenge with the same birds:

Begin, murderer. Pox, leave

thy damnable faces, and begin! Come, the croaking raven doth

bellow for revenge.

The crow or corvid family have been associated with doom-laden myths and legends for centuries, making Hallowe’en a particularly suitable time to be thinking about them. From Aesop in 6th century BC Greece up to Ted Hughes’ malevolent Crow, they have been renowned as messengers, mischief-makers, and bringers of bad luck, even death. It may be because of their habit of scavenging from dead bodies, or their distinctive calls, particularly the deep “pruk, pruk” of the raven or the cacophony of a rook colony. As a child I was told it was unlucky to see a single magpie, and taught to count them using the rhyme one for sorrow, two for joy, three for a girl, four for a boy, five for silver six for gold, seven for a secret never to be told.

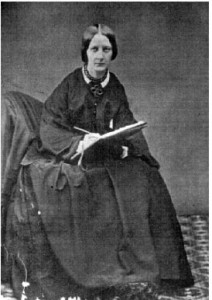

Lots of books have been written about Shakespeare’s birds, but back in 1899 Crows of Shakespeare was published. The author and illustrator was Jemima Blackburn (nee Wedderburn), who accompanied each image by the appropriate crow-related quotation. She was born in 1823, the daughter of the solicitor-general for Scotland, and her privileged family was connected to the most important people in the land. At 17 she spent three months in London where she met the Duke of Wellington, and she was later presented to Queen Victoria. In spite of her background, she was almost completely self-taught as an artist.

Her illustrations of birds and animals were highly regarded, and exhibited in London and New York. Her Dictionary of National Biography entry suggests that she was in the first rank of Victorian ornithological illustrators and describes her as one of Scotland’s first major modern women artists.

She was also an acute observer of bird behaviour. In the 1882 edition of The Origin of Species Charles Darwin acknowledged that she was the first to record how the baby cuckoo ejects its rivals from the nest. The great wildlife artist Landseer was so impressed with her work he gave her some lessons, and John Ruskin took a keen interest in her work.

It was after her marriage to Mathematics professor Hugh Blackburn in 1849 that she began to shine. Together they turned the Roshven estate on Moidart, a virtually inaccessible part of Scotland, into a summer destination for many of the most distinguished scientists and artists of the age. As well as drawing and painting birds she found inspiration in the life and landscapes she saw about her. She kept a visual journal in which she recorded her extensive travels and the daily activities of those living and working in rural Scotland.

Her illustrations appeared in books and magazine, and like Beatrix Potter she also wrote her own verses, usually with animal themes, and illustrated them for children. Some of the best-known are The History of Tom Thumb and The Cat’s Pilgrimage. In 1862 she produced her most esteemed book, Birds from Nature. Several examples of her work are included in the University of Rochester’s Robbins Library Digital Project. But from having been so well-known, she has since been almost forgotten.

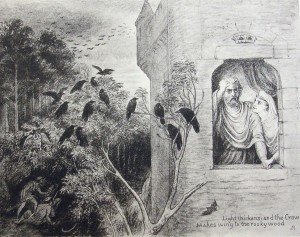

Crows of Shakespeare was one of her last works, and was obviously close to her heart. In her preface she mentions that a “favourite walk on the autumn afternoons was to the fir woods to see the rooks fly home, in a great column, after their day’s foraging in the fertile fields”, echoing Shakespeare’s lines from Macbeth, illustrated in the book:

Light thickens, and the crow

Makes wing to th’ rooky wood.

Her love of Shakespeare began early. During a visit to London she went to both the theatre and opera which sparked her interest in fairy tales and legends. She knew some of the most important literary figures of the day, corresponding with Ruskin and Thackeray, and co-writing an account of travels to Iceland with Anthony Trollope. She saw Fanny Kemble act, saw Charles Kean play Macbeth on tour, and met him. In 1848 she came to the Midlands, visiting Warwick, Stratford and Leamington, and it seems likely that she visited Shakespeare’s Birthplace. In spite of living largely in rural Scotland, Shakespeare remained in her mind. In her modest preface to Crows of Shakespeare she suggests that the book “may interest those who care for Crows, and induce young people to read Shakespeare”.

Jemima Blackburn did care for crows, and perhaps she also knew that early in his career Robert Greene had described Shakespeare himself as an “upstart crow”.