In an earlier post on the subject of Juliet’s balcony, I talked about the original staging of this scene, and how the scene came to be known as “the balcony scene” even though in Elizabethan England the word balcony was not used, let alone by Shakespeare.

It made me think about how many ways I’ve seen this scene staged, and how many pitfalls it can present. Some of these relate to the space in which the scene is staged: in Shakespeare’s theatres the option to use a balcony at the back of the stage could have made it difficult for those at the sides or high up in an upper gallery to see. In nineteenth century theatres built with a proscenium arch upper galleries tend to over-hang the stalls resulting in the effect which I remember well from the Aldwych Theatre where the view from the rear stalls was like looking through a letter box. Anything high up was invisible unless it was way upstage. This theatre took transfers from Stratford and sets designed for the RST stage often had to be cut down to fit the smaller theatre with its difficult sightlines. Thrust stages or fan-shaped auditoria can have their own problems: the National Theatre’s Olivier stage offers unobstructed views from all over the house, but the audience can feel distant from the stage and being able to see from three sides makes designing a balcony tricky if it’s to be anywhere near the front of the stage.

Russell Jackson’s book Romeo and Juliet, in the Shakespeare at Stratford series published by the Arden Shakespeare, documents in detail performances of the play from 1947 to 2000. Fifteen productions and fifteen solutions to staging the balcony. He points out: “Despite the scene’s customary name – and a well-established theatrical and pictorial tradition – the lines nowhere refer to a “balcony”, and the action does not necessarily require one: but simply appearing at a window allows Juliet little scope for movement”.

Directors and designers have to ensure the lovers can be seen and heard, so there’s a tendency to bring them forward. Every production finds its own solutions, but there are many questions: Where should the balcony be: in the centre or to one side where it’s easier to see both Romeo and Juliet? How high should it be? Should it be part of the permanent set, or a structure moved into position specially for the scene? Should Juliet be remote and unattainable, or is Romeo able to get to her on her balcony? Jackson again:

“No stage direction, actual or implicit, required him to climb up to it, but, as we shall see, many productions have been unable to resist the temptation”. Re-reading Russell Jackson’s authoriative book reminded me of some of the best and worst solutions I’ve seen, and I searched the internet for some visual examples.

I was delighted to find the whole scene from the RSC’s 2010 production at the Courtyard Theatre filmed. Sam Troughton and Mariah Gale are both excellent though filming from several angles makes it easy to forget it was a stage performance, and to me she looks awkward with nothing to lean on or stand behind. And why the intimidating metal railings when he is able to get round them? In his book Jackson asks “Should Romeo and Juliet touch hands at any point?” but this pair, in modern dress, do far more than just hold hands.

There is some great material on this production on BBC Shakespeare Unlocked

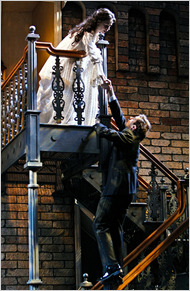

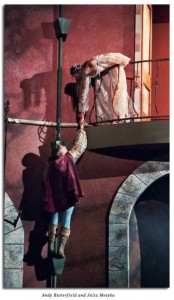

At least Troughton has to make an effort to reach Juliet: in the photograph here, Sonny Valichti could easily reach his Juliet if he used the stairs just to the right (one of the drawbacks of a permanent set is that the balcony serves other purposes and can usually be accessed by a staircase which kind of spoils the illusion).

In Terry Hands’ romantic Italianate production in 1989 Juliet was positioned on the top level of the Swan stage, much too far away for her Romeo, Mark Rylance, to reach her, so they really did have nothing but the words. The scene, after all, is about promise, not fulfilment.

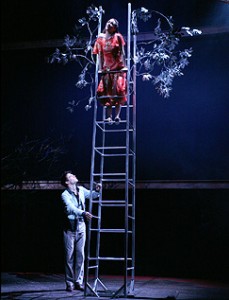

And I know the audience is expected to use its imagination but the bare metal ladder that came up through the stage floor in the 2006 RSC production really didn’t do it for me, with Juliet having to balance precariously on its rungs.

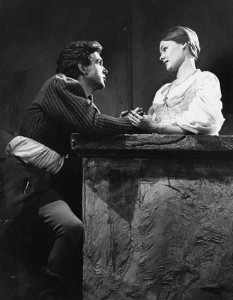

I thought the 1980 production at the RST got the balance about right. Judy Buxton appeared above a plain white wall that had swung downstage to bring her closer to the audience, enough to keep her separate from her Romeo but not so high that they couldn’t touch hands briefly.

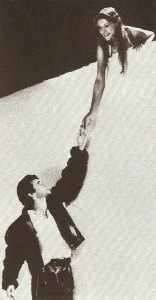

I also like the one from the Marin Shakespeare Company, though seen just as a still photograph the drainpipe looks as if it could have comic potential.