In the latest edition of Theatre Notebook, published by the Society for Theatre Research, June Schlueter* considers the connection between Hamlet’s “tables”, and the two exceedingly rare drawings that have come down to us showing us what the Elizabethan playhouse looked like, The De Witt drawing and the Peacham drawing.

She considers, first, what table-books were like, quoting an essay by Peter Stallybrass and others published in Shakespeare Quarterly in 2004. So completely have table-books disappeared from our world that the essay was necessary to explain how these once-common objects looked and were used. These were small pocket-sized notebooks, the pages waxed so that one could write or sketch using a stylus with a metal point. They were used for making notes while on the move – the contents would be transferred to a more permanent form later, when ink and paper, and something to lean on, were available. The wax surface could then be wiped over and made ready for re-use. Apparently one survives in the Folger Shakespeare Library, a rare survival.

A search for contemporary references yields many hits, including advice for a gentleman as he checked the state of his fields, to “take out his tables, and wryte the defautes” and an observation by John Aubrey that Sir Philip Sidney “was often wont, as he was hunting…to take his table-book out of his pocket, and write down his notions”. Hamlet, too, talks about how notes could be made in a table book and later erased once it had been copied:

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past

That youth and observation copied there…

O villain, villain, smiling, damned villain!

My tables! Meet it is I set it down

That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain.

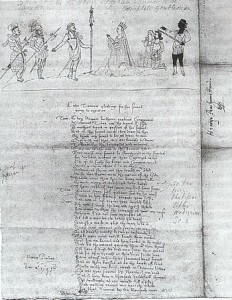

Hamlet’s is not the only mention of tables in drama: in Antonio’s Revenge for instance there is a stage direction “Balurdo drawes out his writing tables, and writes”. Schlueter considers the role of the table-book in the evolution of the two drawings of the theatres. It’s been noted that the Peacham drawing does not illustrate an exact moment in Titus Andronicus, but so rare is it that the depiction of people wearing a blend of Elizabethan and Roman dress is taken as firm evidence for how actors were costumed. There are mysteries about the manuscript: the image appears above a passage from the play which does not match up with the 1594 quarto. Was it added later? The image, in ink, must have been copied either from memory or from a sketch made on the spot in a table-book. Henry Peacham who made the book made many drawings and even wrote a guide to how to draw.

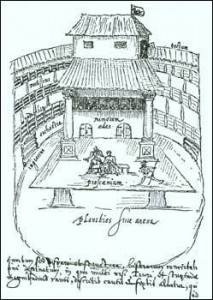

The De Witt drawing has a convoluted history. The original, now lost, was made by De Witt, and the image we now have is a copy of it made by Van Buchell. It shows the Swan Theatre and there has been much discussion about its accuracy. Schlueter suggests again that De Witt may have made his first sketch while in the theatre on his table-book, transcribing it when he had writing materials available. De Witt too spent much time making sketches of antiquities and from the evidence of those it seems likely that he made a further copy that he sent to Van Buchell which his friend re-copied. While this complexity of this process removes the sketch even further from the existing copy it could also remove the possibility of De Witt’s memory playing him false by ensuring he had an accurate image made on the spot.

There is far more in June Schlueter’s thoughtful essay* that may help to explain the process by which we are still able to see these two early sketches of the Elizabethan stage and if you’re interested it’s worth chasing it up. Their survival is indeed something of a miracle given the fragility of the images, particularly if the first version of both was made on a wax tablet to be erased.

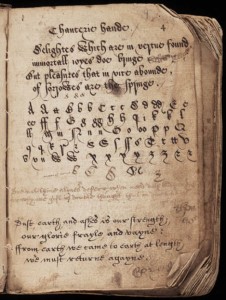

The notes made on a table-book would have been transcribed, probably into a commonplace book, used for keeping all kinds of writings. Schlueter quotes one in the British Library that contains “autographs and dedications… a miscellany of jottings…[and] instructions on making inks of various colours”. In the last few days the Beinecke Library at Yale University has posted on Twitter an image from a wonderful commonplace book in the Osborn collection compiled by Englishman William Hill in the 1570s. This link leads you to the digitised images of this amazing survivor, battered and heavily-used. Hill used it for practicing different kinds of handwriting as well as for keeping verses and mottoes. He seems to have favoured proverbs that reminded him of the transience of life. One reads “And whosoe withered is with yeares/ may not be yonge againe”, a sentiment that Shakespeare would have agreed with.

*June Schlueter. “Drawing in a Theatre: Peacham, De Witt, and the Table-book”. Theatre Notebook 68 (2014): 69-86.

Very interesting and useful. Thank you Sylvia.