Today there are few places where you will see the name of Flower in Stratford-upon-Avon apart from in a pub, but a hundred or even fifty years ago Flowers Brewery was one of the major employers in the town with a large building along the Birmingham Road, before being taken over, after which the making of beer ceased.

The brewery in Stratford was founded in 1831 by Edward Fordham Flower and by the 1860s two of Edward’s three sons, Charles and Edgar, were running the brewery in partnership with their father. It was a hugely successful business that made the Flower family wealthy. But the influence of the Flower family in the town has been much more wide-ranging, indeed without the Flower family the Royal Shakespeare Theatre would probably not exist.

I’m going to confine myself to Edward Fordham and his eldest son Charles Edward, the key figures in enlarging the Shakespeare industry in the town. Soon after founding the brewery Edward began to be involved in the running of the town. He must have been a man of extraordinary energy. He became Stratford’s mayor four times, the final time coinciding with the Tercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth in 1864, when the most magnificent of celebrations were planned including the building of a massive pavilion and over a week of events including performances of plays by Shakespeare featuring some of London’s famous actors.

Celebrations were also planned in London, with committees of well-known men behind them, and the Stratford organisers felt under pressure to put on a good show despite their inexperience in staging theatrical events. In the end they need not have worried. The Times, writing about the London committee commented “in various circulars which we have all seen the committee is described as made up of 400 persons, some of high status and repute. But these are mere names”. When it came down to it the London celebrations were greeted with “utter apathy”, with theatres merely putting on Shakespeare productions already in their repertoire, and a note that “even the proposed banquet has fallen through”.

For many in Stratford, the celebrations were seen as successful, but the jollifications came at a price. It had been hoped sufficient money would be raised to pay for a memorial to Shakespeare, but in fact Flower ended up having to cover the considerable deficit himself. James Cox, who followed Flower as the next mayor, wrote a retrospective complaining that the festival had been too ambitious, and should have limited its aims: “the erection of a monumental memorial was the one thing the committee should have striven for”. An additional aim had been to fund scholarships for worthy students, but this too had to be abandoned.

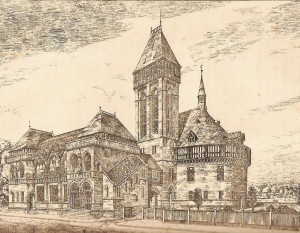

The Tercentenary also planted the seed of the idea for a permanent theatre for Shakespeare, not merely a temporary pavilion or the small theatre that stood, almost unused, in Chapel Lane. And it was Edward’s son Charles who took it upon himself to do something about it. The proposal to found a permanent theatre in such a provincial place was greeted with scorn. Just before the foundation stone of the theatre was laid in 1877 the Daily Telegraph wrote: “We beg distinctly and indignantly to protest against the whole paltry and impertinent business… They have no mandate to speak in the name of the public or to invest with the attribute of a national undertaking …[what is] to be half theatre and half mechanics institute… The Governors and Council are respectable nobodies”.

Flower kept silent, but he did not forget this insult. When he rose to speak at the ceremony for the opening of the theatre over two years later he referred directly to this article: ” A new line of criticism has been taken up by some who say we are presumptuous in undertaking it. They say we do not represent literature, science, scholarship, clergy or law; they say we are not inhabitants of that great metropolis which ought to monopolise such great works. They say, in fact, we are a set of Respectable Nobodies! All I can say is that, the “Nobodies”, having waited three hundred years for the “Somebodies” to do something, surely blame ought not to attach to us; rather let criticism be given to those great social and literary “Somebodies” who have done nothing.”

He continued: “It is quite true we are nobodies. We know that, and therefore do not despair because we cannot accomplish great things at a single effort. We shall be ready to go on quietly and patiently with our work, knowing that we do so in a true spirit of love and reverence for the great man for whose memory we do it”.

“Many of the great somebodies would have been willing enough to have joined our ranks, only that we desired to admit those only who were willing and able to give some real assistance: we don’t want names only. How many similar projects have been started, with long lists of committees, and patrons, and presidents – great and illustrious names, and names only – which have collapsed because the real hard-working element has been overwhelmed by the ornamental superstructure”.

Anybody who feels for the underdog couldn’t help but cheer at this dignified but powerful speech. But even this did not stop the comments. Flower himself had to dip his hand into his own pocket again to ensure the theatre was completed, and the it became known, again disparagingly towards the business in which Flower had made his money, as “The theatre built on beer”.

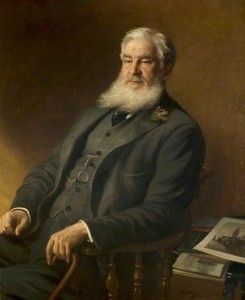

Today, we are likely to feel rather differently about someone with such philanthropic aims. Flower was true to his word. although he contributed massively to the theatre, it was always for Shakespeare’s benefit, not for Flower’s. I particularly like the way that in the portrait of Charles Flower above, just by his elbow on the right of the picture is part of an image of the 1879 building which he had been responsible for. Within the RST there are barely any references to the family that made it all happen. Without them Stratford might never have got anything more with which to celebrate its most famous son than a memorial statue. Instead Shakespeare got the memorial that he needed, a theatre devoted to the performance of his plays, a tradition that has carried on ever since 1879 and shows no sign of failing.

There is more about the history of the Flower family’s involvement with brewing in this blog .

It is sad that as Liz Flower has also pointed out, almost all references to the Flower family have been eradicated from the theatre.