James Fox’s three-part documentary series A Very British Renaissance has just finished on BBC 4. It was first shown in 2014, and having missed it first time I’m very pleased to have caught up with it. The presenter, an art historian, has found some wonderful and unfamiliar items representing the British Renaissance from 1500 to the 1640s that make the series very much worth watching.

Fox’s premise is that the British had its own Renaissance, and although the resulting arts were “a bit rough around the edges” they were significant and should be better recognised. Unfortunately his insistence on mentioning the Renaissance kept bringing to my mind visions of Michelangelo’s David, the Sistine Chapel, and Titian’s glorious paintings. I’d have preferred to celebrate the artistic achievements of this country and the wonderful collections documenting them.

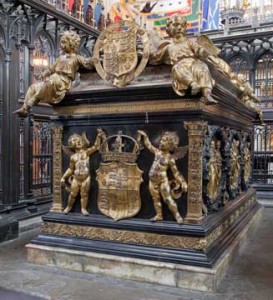

His first example was the tomb of Henry VII and his queen in Westminster Abbey, dating from after Henry’s death in 1509. The gilt bronze effigies, by Italian sculptor Pietro Torrigiano, are behind a grille, so it was a treat to see them and the chubby cherubs which Fox claims define this work as the first of the English Renaissance. In this programme he looked at how foreign artists imported Renaissance ideas, and examined the work of Hans Holbein, a real star of Henry VIII’s court, beginning with the immensely popular National Gallery painting, The Ambassadors, then moving on to stunning portrait sketches in the Royal Collection. It was worth watching the whole programme just for these. English artists took inspiration from the Europeans: Thomas Wyatt in poetry and Thomas Tallis in music. Tallis apparently wrote Spem in Alium, his choral work written in 40 parts in response to an Italian motet. It apparently beat the Italian piece hands down.

The second programme looked at “the development of artistic ideas in Elizabethan England. An age obsessed with secrets, with poets writing in code and artworks and buildings concealing hidden messages.” Many of these hidden messages related to the religious upheavals of the time, when the country moved from Catholic to Protestant, back to Catholic and finally back to Protestant within a few dizzying decades. With the consequences of being on the wrong side possibly being a horrific execution it is hardly surprising that people concealed their feelings. Architecturally he looked at the buildings created by Thomas Tresham, the triangular Lodge at Rushton and the unfinished Lyveden New Bield which subtly reveal their builder’s strong Catholic faith.

The programme also examined the British hunger for exploration and discovery. I’m not sure that mathematician, astrologer and mystic John Dee was really responsible for Queen Elizabeth’s decision to explore and conquer foreign countries and create a British Empire, but Fox combined the two elements of secrecy and exploration when talking, inevitably, about Shakespeare. In its energetic, emotional and hugely popular homegrown drama, Britain has no need to feel second-rate compared with Europe. Fox chose to focus, again, on John Dee, suggesting he might have been the model for Prospero in The Tempest. Aged over 80, Dee had died shortly before the play was written, but in his time he had been known throughout Europe. It’s not impossible, but Shakespeare needed no real-life inspiration for his god-like magician.

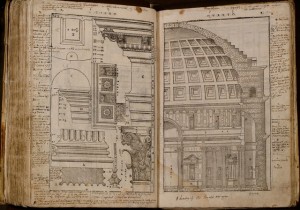

The third programme looked at how, around the time of Shakespeare’s death, tensions grew between the real world and the world of the royal court. The man whose work symbolised this split was architect Inigo Jones. Fox examined another amazing treasure kept at Oxford’s Bodleian Library, Jones’s own heavily annotated copy of Andrea Palladio’s The Four Books of Architecture. Jones’s first building in the Palladian style was the glorious Queen’s House in Greenwich, which promised much for the future. But while Robert Burton was unlocking the secrets of the mind in his Anatomy of Melancholy, and Gabriel Harvey was working out the circulation of the blood, the court commissioned the talented Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones to create vastly expensive court masques, entertainments that had nothing to do with the lives of ordinary people. In the end, this divergence led to the Civil War of the 1640s.

British culture went underground during the period of the Commonwealth, with every artistic activity banned. Fox’s point is that we tend to ascribe the artistic flowering of the country to the period after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660s. In the series, he’s demonstrated that, in fields other than drama, Britain had its own renaissance before that date, that “changed British culture forever”. For Shakespeare-lovers, it provides an insight into the culturally shifting world he inhabited.

A couple of reviews of the series from its first airing by The Guardian and the Telegraph. It’s now available to watch on the BBC IPlayer here , and even if you don’t watch the whole thing, do take a look at the clip of the Holbein sketches.