It’s been a good many years since I looked at Anthony Burgess’s 1970 biography Shakespeare. While working in the library at the Shakespeare Centre I always favoured Samuel Schoenbaum’s Documentary Life, so safely based on verifiable facts. Burgess was a great writer, but like Shakespeare he sometimes wasn’t very respectful of his sources when they got in the way of a good story. Nowadays it’s much easier to lay your hands on those documents (virtually or in print), so it’s exactly the right moment for the Folio Society to bring out a new edition of Burgess’s “speculative biography“.

Unlike the more scholarly biographies, Burgess’s book is highly personal, and eloquently written. He claims “the right of every Shakespeare lover who has ever lived to paint his own portrait of the man”. Although based on the facts where they exist, Burgess also uses his own inventive imagination to fill in the gaps, charmingly disarming potential criticism with his honesty. “The reader will recognise the fiction writer at work and, I hope, will make due allowance”.

In his chapter on Marriage he comments on the lack of evidence before writing “I propose to indulge myself in an onomastic fancy that the hard-headed reader is welcome to ignore”. After a digression on the subject of the names of Shakespeare’s children he writes “The whole of this paragraph is very unsound”.

Frustrated by the lack of descriptions of Shakespeare on stage, Burgess writes his own. Chapter 15 imagines the first performance of Hamlet, with Shakespeare, naturally, appearing as the Ghost. As you would expect from Burgess, it’s masterfully-written. He sets the scene: “It is broad daylight and the autumn sun is warm, but words quickly paint the time of night and the intense northern cold…Then the ghost appears, Will Shakespeare, the creator of all these words but himself, as yet, speaking no words”. The chapter on Drama eloquently digresses into a consideration of the history of theatre and plays from the Greek and Roman period onwards.

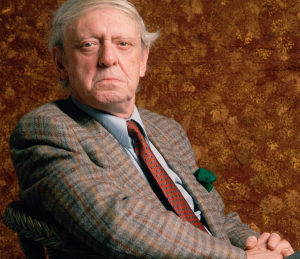

Since at least the early 1970s Burgess has been best known as the author of the disturbingly violent novel A Clockwork Orange, published in 1962 and turned into a cult movie by Stanley Kubrick in 1971. Sandwiched between these two events Burgess spent much of his time thinking and writing about Shakespeare. He first wrote a novel, Nothing Like The Sun: A Story of Shakespeare’s Love Life, published on 23 April 1964, bang on the quatercentenary. As a result he was commissioned to write a musical on the same subject, intended to become a Hollywood film. When the idea was dropped Burgess instead recycled the music into a ballet suite, Mr WS, that was broadcast on BBC Radio. Then he wrote his biography Shakespeare.

Later on he continued to write about him. Shakespeare appeared as a character in two short stories and in A Dead Man in Deptford, a novel about Christopher Marlowe, published in 1993, the year Burgess died of lung cancer.

There is much information about Burgess’s prolific career on the International Anthony Burgess Foundation site. This page includes a link to an early recording of Burgess talking about Shakespeare.

He identified himself with Shakespeare. In an essay on the IABF website Victoria Brazier notes that “where many writers would seek inspiration for their work from Shakespeare’s plays, Burgess rather makes assumptions about Shakespeare’s life by examining his own”. She also notes that Burgess, whose real name was John Burgess Wilson, harboured a hope that he was related to an actor in Shakespeare’s company. “Jack Wilson was one of the company of players to which Shakespeare belonged, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. (Jack being what Oscar Wilde’s Gwendolen would call dismissively ‘a notorious domesticity for John’.) Through some mistake of printing or transcription, Jack Wilson’s real name is inserted into the First Folio’s version of Much Ado About Nothing rather than that of his character, Balthazar. A stage direction in the second act reads, ‘Enter Prince, Leonato and Jacke Wilson’.

The final words of the book illustrate how for Burgess, Shakespeare was everywhere: “We need not repine at the lack of a satisfactory Shakespeare portrait. To see his face we need only look in the mirror. He is ourselves, ordinary suffering humanity, fired by moderate ambitions, concerned with money, the victim of desire, all too mortal. To his back, like a hump, was strapped a miraculous but somehow irrelevant talent. It is a talent which, more than any other that the world has seen, reconciles us to being human beings, unsatisfactory hybrids, not good enough for gods and not good enough for animals. We are all Will.”

Like all books published by the Folio Society, the book is a pleasure to hold, and handsomely produced. It also features a new introduction by Professor Stanley Wells who notes that the book has stood the test of time and will continue to do so “because of its interaction between the imagination of a major novelist and the life and work of the greatest of poetic dramatists”. The book may not be a sober assessment of all the facts about Shakespeare’s life, but it’ll tell you more than most biographies about Shakespeare the human being.

Fully agree. Not that scholarly, but homologous nevertheless………enjoyed Schoenbaum’s more – similarly Sir Frank Kermode’s concise work of 2004.

I bought this book because Stanley Wells endorsed it……..enough for me.

Read two chapters so far…….so far so good.

Thanks for the reminder, I just pulled this out off my library shelf, its a first North American edition but it has some water staining unfortunately. I found it at a garage sale needing a home. The Folio Society edition looks lovely. Must say I enjoyed his “A Dead Man in Deptford”.