![william-shakespeare-portrait[1]](https://theshakespeareblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/william-shakespeare-portrait1-300x300.jpg) In writing posts for this blog I’ve looked at lots of the myths surrounding Shakespeare’s life. They cover almost every aspect of his life: who he married, and where, what he looked like, whether he was gay or straight, whether he took drugs.

In writing posts for this blog I’ve looked at lots of the myths surrounding Shakespeare’s life. They cover almost every aspect of his life: who he married, and where, what he looked like, whether he was gay or straight, whether he took drugs.

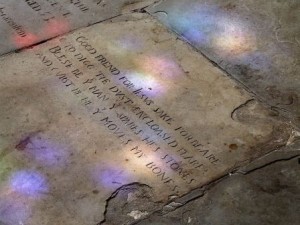

In the last couple of weeks one of the most obscure of these legends has hit the headlines. It’s suggested that Shakespeare’s skull was stolen from Holy Trinity Church as a bet, and has been discovered in a church in Beoley near Redditch. Over the centuries the rhyme on Shakespeare’s tomb cursing anyone who moves his bones has given many people the idea of doing just that, and the gravediggers’ scene in Hamlet has also inspired people to think about unearthing the dead.

For clarification about the story I went back to a favourite book, Samuel Schoenbaum’s Shakespeare’s Lives. This is his account: “After Garrick’s Jubilee, it was reported, Horace Walpole had promised George Selwyn three hundred pounds for Shakespeare’s skull, if he could come by it. Years later, in 1794, a young doctor named Frank Chambers took up this sporting offer; breaking into Stratford church by night, he procured the skull with the aid of local ruffians. But the master of Strawberry Hill declined to buy, and the memento mori found its way to the family burial vaults of the Sheldons, presumably hard by to the Beoley parish church in Worcestershire, where so many Sheldons were interred. So the story goes, but it was first published (in part) almost a century later, in the Argosy for October 1879, and five years later extended into a pamphlet, How Shakespeare’s skull was stolen and found, by “A Warwickshire Man”. The author, C L Langstone, happened to be the incumbent of Beoley Vicarage. His narrative reads like what it must surely be a lurid fiction”.

I took a look at the 1884 pamphlet. Here is the description of how Chambers and his companions broke into the church:

“I thought we never should get inside that church. The windows were far above our heads, and well protected by stout stanchions. Dyer, who had served in a smithy, worked with a will at the lock of the chancel door, using the tools I had brought; but then these confounded old locks have a way of keeping close, and it would not yield”….”I crept round towards the porch, and, resting on a mound, I plainly heard footsteps on the broad flags in the avenue. I crept nearer. The overhanging boughs, with remnants of leaves, made it too dark to distinguish any form. I doubt if I could have seen a ghost; but I was within a few feet of the heavy tread of a man… At length (it seemed an hour) he moved rapidly away; and having reassured my companions, we returned to the charge. The door was soon opened, and, tinder-box in hand, we groped our way to the great chancel, and with considerable difficulty, for the letters were much worn, I singled out the slab, then about three feet by seven feet, which covers the remains of Shakespeare. ”

Langston took care to get local details right, but to give him his due, I doubt if he expected the story to be seen as more than fiction. The story was published nearly a hundred years after the events are supposed to have taken place. The anonymous writer states that his main source of information is another anonymous man, Mr M, now conveniently dead. Mr M got the story from his uncle, who claimed he had opened the grave decades earlier. Not even the challenge said to have been made by Horace Walpole is documented.

Mr Langston in fact took a leaf in fact out of Horace Walpole’s own book The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764 and known as the first gothic novel. It was a hoax. Walpole published it anonymously, passing it off as a translation of a manuscript rediscovered in the library of “an ancient Catholic family in the north of England” and the story was supposed to date back to the middle ages. He invented the manuscript and its alleged author “Onophurio Muralto”, and took “William Marshal” as his pseudonym. Walpole was a Shakespeare fan and the story owes quite a lot to Hamlet, with its theme of incest, hauntings, mistaken identities and unhappy marriage. It was only with the second edition that Walpole owned up.

Langston’s first venture was published in 1879, by which time there were plenty of other similar novels. Take for instance Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, first published in 1868. This book begins with a prologue about the mysterious moonstone “extracted from a family paper” from 1799. The first part of the book is entitled The Loss of the diamond, the conclusion The Finding of the diamond”. The whole story is told as a series of witness statements in a legal case and is widely known as the first detective novel. Langston’s story is also based on statements by a number of different voices, and is divided into How Shakespeare’s skull was stolen and How Shakespeare’s skull was found.

No wonder barrister Charles Mynors, Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester, has ruled that there is nothing to link the unidentified Beoley skull to Shakespeare, and has thrown out the application for DNA testing. As a barrister he must have heard many an unlikely tale spun, though few can have been as odd as this one. Here is the link to Emily Gosden’s uncritical report from the Daily Telegraph.

It’s a great story, well-told by Langston, but I’m afraid it’s Much Ado About Nothing.

Yes Shakespeare academics must get really fed up with the seemingly endless conspiracy theories and myths conjured up by people who clearly have too much time on their hands. These are always given lots of publicity by the uncritical press.

It’s interesting that you should mention the “Moonstone” by Wilkie Collins as a diamond called the Blue Moon (apparently worth $35 million) is about to go on sale.