We only have a few examples of Shakespeare’s handwriting, but those that we have suggest that he wasn’t a particularly neat writer. I always like that section in Hamlet where the Prince explains how he had to remember his lessons in penmanship in order to replace the commission that was to condemn him to die:

I sat me down,

Devised a new commission, wrote it fair –

I once did hold it, as our statists do,

A baseness to write fair, and laboured much

How to forget that learning, but, sir, now

It did me yeoman’s service.

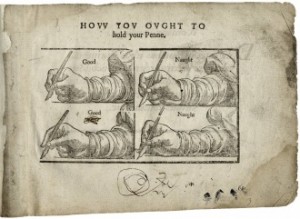

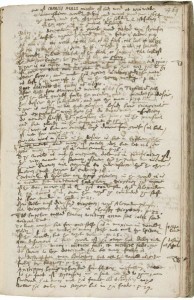

A new project has just been launched that will allow anyone, from any country in the world, to have a go at learning how to decipher handwriting of Shakespeare’s period. It’s a crowdsourcing project in which people are being asked to help transcribe early handwritten documents. Many manuscripts were written in what was called secretary hand, which can be fiendishly difficult to read, but don’t be put off if palaeography isn’t your thing. First of all users can take a tutorial to get them started, and then they’ll be able to try to puzzle out the document or letter.

On 8 December, just before the project launched, the Guardian published an article Where there’s a Quill, in which Dr Victoria Van Hyning, part of the Zooniverse team explained “Most manuscript material isn’t machine readable – you can’t have a computer pick out words or make it word searchable”. The transcripts will be searchable online just as many printed sources are already. Entitled Shakespeare’s World, the project is based on the many thousands of documents in the care of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. Here is a description from the website of how it will work:

The process is simple: Register for an account, view a manuscript, and begin transcribing. All contributions are welcome and transcribers can go at their own pace. The first phase of the project will focus on ‘receipt’ (recipe) books and letters. Later, the project will add miscellanies, family papers, legal, and literary documents.

Once the manuscript images are fully transcribed and vetted, they will be entered into the Early Modern Manuscripts Online, or EMMO, database. EMMO is a multi-faceted project at the Folger that is funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). Once the database is implemented in late 2016, scholars will be able to search the transcriptions and associated metadata in the free EMMO database for any word or phrase from these manuscripts, greatly expanding our capacity for understanding the world in which Shakespeare lived.

“We look forward to building and connecting with new communities of transcribers and creating new forms of access to the Folger’s incredible collection of manuscripts,” says Heather Wolfe, curator of manuscripts and the principal investigator for EMMO.

The project brings together organisations on both sides of the Atlantic: the Folger Shakespeare Library’s Early Modern Manuscripts Online project, Zooniverse.org at Oxford University, and the Oxford English Dictionary of Oxford University Press. If you’re interested in the nuts and bolts about how the project has been set up, here’s a post that was put up back in Spring 2015 while it was still being developed.

Here too is a link to a page about manuscripts that accompanied a Folger exhibition on letterwriting in 2004.

The fun for people doing the transcribing will be go get closer to how people really lived in early modern England. Although many are from Shakespeare’s lifetime, it’s unlikely that any will relate to the man himself, but many will be personal documents relating to his contemporaries, so transcribers will probably discover details of daily life they wouldn’t get by simply reading descriptions. Dr Van Hyning explains that the increased knowledge of the content of the manuscripts is not just for academics: . “This would definitely be one of the more complete resources for shedding light on what was it like to prepare a meal in this period, to balance the accounts for your household, to try to co-ordinate the education of your children, to get on the wrong side of the law, arrange a marriage – you name it.”

Other benefits will be that additional elements of the documents will be noted such as wax seals and drawings, and the OED people are hoping that people will discover new words and variants that will get added to the dictionary.

Those who join in will know they’ve helped a major project that will be used for decades to come and learnt a new skill that could easily be transferable, for instance if investigating their own family tree or doing historical research. Definitely worth a try, I’d say.