On 27 July 1967 the Sexual Offences Act received Royal Approval in the UK, making private homosexual acts between men over the age of 21 legal. In the intervening fifty years attitudes have changed profoundly. Back in 1953 the newly-knighted John Gielgud, the greatest Shakespearean actor of his time, was arrested, charged and fined for soliciting. Within hours the story was on the front pages of the newspapers and Gielgud, in rehearsal for a play in the West End, faced terrible humiliation. Perhaps coincidentally, in 1954 the Wolfenden committee was set up to look at the law and when it reported announced, more or less, that what consenting adults did in private was not the law’s concern.

On 27 July 1967 the Sexual Offences Act received Royal Approval in the UK, making private homosexual acts between men over the age of 21 legal. In the intervening fifty years attitudes have changed profoundly. Back in 1953 the newly-knighted John Gielgud, the greatest Shakespearean actor of his time, was arrested, charged and fined for soliciting. Within hours the story was on the front pages of the newspapers and Gielgud, in rehearsal for a play in the West End, faced terrible humiliation. Perhaps coincidentally, in 1954 the Wolfenden committee was set up to look at the law and when it reported announced, more or less, that what consenting adults did in private was not the law’s concern.

That Gielgud’s career and reputation was not wrecked was due to the support he received from his professional colleagues and the tolerance of audiences who were more interested in his acting than his personal life. There have always been gay people in the arts, whether or not their sexuality has been discussed publicly.

In that relatively short period of fifty years changes have been massive. Now exuberant LGBT Gay Pride events are held around the world, under the rainbow flag symbolising diversity and peace.

In that relatively short period of fifty years changes have been massive. Now exuberant LGBT Gay Pride events are held around the world, under the rainbow flag symbolising diversity and peace.

The BBC’s current Gay Britannia season celebrates that diversity and the nation’s artistic success. The photographic exhibition Love Happens Here documents the LGBT community in London. There’s a celebration of E M Forster’s novel Maurice and a series of programmes by Simon Callow about the history of the representation of gay sexual relationships in the arts. He has already discussed how nineteenth century artists commented on male sexual relationships and in the episode on 24 July he will talk about how theatres and music halls across Britain endlessly explored sexuality, gender and difference while managing to avoid the censors.

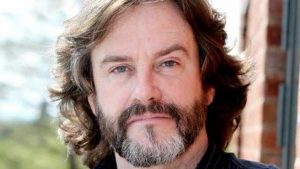

Inevitably Shakespeare is involved in this debate, and RSC Artistic Director Gregory Doran was invited onto Radio 4’sToday programme on 21 July to talk about whether Shakespeare was gay or not. There is an extract of the interview here, and the full five-minute interview can still be listened to as part of the Today programme. It begins at 1hr 43 minutes in. This article in the Telegraph is based on the interview.

Gregory Doran and Antony Sher were branded “Theatre’s leading gay power couple” in this 2015 article . They have been partners for thirty years, became civil partners in 2005 and married in 2015.

Actors and directors, particularly in the theatre, know Shakespeare’s plays more intimately than anyone else, committing them to memory and making sense of the words in order to speak them. Doran, first as an actor then as a director, has been doing this for over thirty years and his opinion has considerable weight. He finds that Shakespeare frequently writes from the point of view of the outsider, like the Jew Shylock and the Moor Othello, and suggests Shakespeare may have felt himself to be an outsider, perhaps as a result of his sexuality. He also points out, though, that as a gay man himself, he may be casting Shakespeare in his own image, just as every biographer has done.

With Shakespeare, of course, nothing is simple. When he wrote his plays, the actors performing them were men. Might Romeo and Juliet have been unconvincing, their sexuality ambiguous? Shakespeare solved the problem by keeping the would-be lovers apart in the balcony scene, making them declare their love in beautiful words rather than actions. And Shakespeare had no trouble writing about heterosexual desire in his long erotic poem Venus and Adonis.

Doran repeats the suggestion that Shakespeare’s sonnets, the most personal of poems, are overwhelmingly addressed to a man. Many editions have certainly heterosexualised them, replacing “he” with “she”, but there is always a question mark about them. The sonnets were published in 1609 without Shakespeare’s permission. When a selection was reprinted some thirty years later the then-publisher changed the order, giving sonnets titles and conflating some of them. The original publisher too might have rearranged them in order to provide a developing “story”. Read individually there is often nothing to indicate the sex of the addressee. In their edition, Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson recommend this approach. Rather than one young man and one dark lady there could be many addressees, of both genders.

The main point of Doran’s interview, though, was to insist that characters such as Antonio in The Merchant of Venice, desperately in love with Bassanio, should be played as gay, rather than toned down. And here he surely has a point. The Gay Britannia season also intends to reveal the discrimination still facing people today. We still have a long way to go before people are treated equally, and before Shakespeare’s words of love can be appreciated regardless of who they address. It’s the love that’s important after all.

I heard the Radio 4 interview and was surprised it wasn’t picked up more in the media. Very interesting and thank you for covering this!