It’s always claimed that Shakespeare must have been fascinated by British history because he wrote so many plays about it. I make the play count thirteen. But was this fascination with the history itself, or did he see it as a source for stories which he went on to turn into plays?

In Andrew Marr’s Start the Week this week on Radio 4, he took the subject of the representation of history in books, in particular its relationship with fiction. His guests included Boris Johnson, who has just published a book on the history of London, and Alison Weir. It was fascinating to hear how these authors approach the writing of fiction as opposed to fact, though I couldn’t help thinking that Alison Weir protested too much about how readers confuse the two. She’s written factual biographies and novels about the same person, as in her biography of Eleanor of Acquitaine and a novel based on her life called The Captive Queen, so it’s hardly surprising that readers get them mixed up.

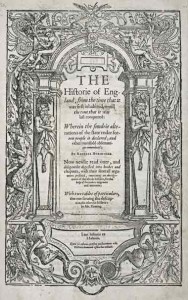

Shakespeare was limited in the resources he could use, and often relied on one or two source books. Liz Dollimore is currently writing a series of blogs about the sources for Shakespeare’s plays and has just posted one about King John, in which Holinshed’s Chronicles are used as the unmistakeable source for part of the plot.

The boundaries between fact and fiction are always fuzzy to say the least, and if Holinshed gets the facts wrong, then Shakespeare will repeat the error. The murderous figure of Richard III with his hunch back was not invented by Shakespeare. He was merely repeating the Tudor myth that the last of the Plantagenet kings was evil through and through, and the Richard III Society and other advocates of the real Richard know they are fighting a losing battle against one of Shakespeare’s most compelling villains and best stories.

In his introduction to the now rather elderly Penguin edition of Henry IV Part 1, P H Davison comments on “the difference between Elizabethan and modern conceptions of the use of history”. History was thought to be educational, but not by teaching lists of dates: “By holding up a mirror to the past it was thought possible to learn how to amend one’s own life and how to anticipate events”. He goes on to explain how Shakespeare’s perceived political conservatism can be seen as a result of his, and of his countrymen’s fear of the consequences of rebellion and disorder, though we’re now much more aware of the subversive elements in Shakespeare’s writing.

In the two parts of Henry IV, Shakespeare juggles material from a large number of sources, giving any modern editor the difficult job of disentangling them. Some elements of the plays are straightforwardly from source books like Holinshed, some are from earlier plays. The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth covers Prince Hal’s “pranks” as well as his conversion on the death of his father, and it’s thought that there may have been an earlier play on the same subject. Then some of the evidence for Hal’s wildness comes from accounts that were circulating during his lifetime, so it’s likely there is some truth in them. The story that Prince Hal boxed the Lord Chief Justice on the ears appears in one of the early plays written before Shakespeare’s, but Shakespeare tones it down by having Falstaff merely refer to it in passing.

Falstaff himself is one of Shakespeare’s great inventions, as are the scenes in Gloucestershire. These scenes have a purpose in the structure of the play, comic relief between the serious political scenes, but also serve to remind the audience of the truly national significance of the accession of the new king, with repercussions felt as far away as Justice Shallow’s peaceful orchard in Gloucestershire.

Falstaff himself is one of Shakespeare’s great inventions, as are the scenes in Gloucestershire. These scenes have a purpose in the structure of the play, comic relief between the serious political scenes, but also serve to remind the audience of the truly national significance of the accession of the new king, with repercussions felt as far away as Justice Shallow’s peaceful orchard in Gloucestershire.

In Henry IV Part 2 Shakespeare was also setting the scene for what he knew would be his great story of national celebration in Henry V. The awareness of history is everywhere in the play, but especially in Henry’s speech before Agincourt.

Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words,

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remembered.

This story shall the good man teach his son,

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by

From this day to the ending of the world

But we in it shall be remembered.

Holinshed’s Chronicles report what King Henry really said to his troops before this battle, and Shakespeare pretty much ignored it to write his own incomparable speech. Samuel Johnson wrote “no good story is ever wholly true”, and thankfully Shakespeare always went for the story.

I am a psychoanalyst/journalist, writing mainly about cinema, media, and popular culture. Also an amateur Shakespearean studies guy. For many years, I’ve been studying and working on the dramaturgy of the oration given by the Archbishop of Canterbury before King and court in Act I, Sc. 2 of HENRY V. Shakespeare essentially translated the speech set down in the Holinshed chronicles into blank verse. I wont go into the central arguments favoring a French invasion. My concern is that the actual Archbishop, Henry Chichele, one spelling, accoring to some sources, never in fact gave the speech, never attended the ‘Great Parliament” at Leicester at which the speech was alledgedly given, and that in fact Holinshed’s sources are to put it mildly doubtful. It’s supposed, and I don’t know the documentation’s reliability, that sometime in the 1540’s, a ‘pseudo-historian’ (or -historians) involved in furbishing the “Tudor Myth”,

created the speech or the basis for the speech, along with other particulars of Henry V’s life, essentially out of whole cloth, in aid of emphasizing the legitimacy of the Tudor line. Do you have any information on any of these scores. The oration itself is very much concerned with the legitimacy or non-legitimacy of dynastic lines, the Archbishop’s most powerful argument for Henry’s claim upon the French throne being that, since both Henry and Charles the Sixth derive their respective thrones through the feminine, the question is which line is ‘purer’ — of course Henry’s.

I’ve heard that the central character in re-inventing Henry’s history was one Campion or Champion or somesuch, and that this gent was writing or rewriting Henry’s life around 1540. Can you enlighten me on any of these matters?

My own work here is essentially dramaturgical. It would be useful to know if Shakespeare ‘swallowed’ Holinshed’s account whole, indeed if the Chronicles themselves, being partly fictional, were considered truthful by Holinshed and his associates. Of course, we can only speculate. From a purely dramatic point of view, I’m mainly interested in what ‘works’ as far as putting the oration, with all its prolixity and arcane subject matter, into some kind of shape a contemporary audience can understand, without doing violence to it. The internal consistency of the play’s arguments are the thing, so to speak. But in aid of good scholarship — and I emphasize I am no Shakespearean scholarship, I do think it would be useful to provide the reader with the alternate readings of the history behind Henry’s reign, and the Archbishop’s speech. Thanks in advance. Harvey Roy Greneberg MD

Thanks for your interesting comment on Henry V. My understanding, backed up by T W Craik’s Arden edition of the play, is that Shakespeare used as his exclusive sources for the play Holinshed’s Chronicles and the earlier play The Famous Victories of Henry V. Both include the Archbishop’s speech justifying the English invasion of France, and you can see by looking at Holinshed that Shakespeare pretty much took it as read, turning it into poetry and adding a few flourishes. Shakespeare’s concern was to write a play, rather than to be accurate about the history and you can find many examples where he got the details wrong. Apparently there are mistakes in Holinshed’s account that Shakespeare simply repeated.

Of course it’s interesting to speculate why Holinshed got his facts about the Archbishop so wrong, perhaps to the extent of making up the speech for political reasons, but it’s my feeling that Shakespeare adopted this official version without much question. I’m not a historian but I’m sure there must be publications which consider this subject in depth.

Good luck with your search for the truth!

Several years down the line, still working on the paper,and have yet to find the contemporary Elizabethan or post-Elizabethan chroniclers/historians who opposed the ‘Tudor myth’, and claimed the Canterbury’s oration was never given at all, but made up out of whole cloth. Once again, does anyone out there know who these dissenters were? Thanks much — Harvey Roy Greenberg MD

Several years down the line, still looking for the anti-Tudor historian or chronicles who disputed that the Canterbury oration was never given in the first place. References would be appreciated. Thanks much. HRG

Hello Harvey, I’m one of Sylvia’s former colleagues at the library & archive of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

The Campion you refer to could be Edmund Campion, Jesuit priest and martyr, who was executed in 1581. He was born in 1540 so would seem unlikely to be your Tudor-myth historian writing in the 1540’s. However he did write a history of Ireland which was revised and incorporated in the second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles by one of its contributors, Richard Stanihurst, who had been one of Campion’s students. I have no idea if this in any way covered the reign of Henry V.

If you are not already aware of it, a handbook to Holinshed’s Chronicles was published last December as part of the Holinshed Project (which is aiming to eventually publish a 15-volume edition of the Chronicles – see the project’s website http://www.cems.ox.ac.uk/holinshed/index.shtml). You can also see the project’s online full text of both editions at http://www.english.ox.ac.uk/holinshed/index.php . The section on Henry V’s Leicester parliament from the 1587 edition (which is the edition used by Shakespeare) is here – http://www.english.ox.ac.uk/holinshed/texts.php?text1=1587_5106 (scroll down). The handbook details are here – http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780199565757.do#.UdA_CTvMBJs . Perhaps one of the editors could help you further – Dr Paulina Kewes has contact details here – http://www.jesus.ox.ac.uk/fellows-and-staff/fellows/dr-paulina-kewes.

I presume you are aware of Edward Hall, lawyer and apparently pro-Tudor historian. His Chronicle (full title The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancaster and York), published in 1547 and which Holinshed drew on, also includes Chichele’s speech at Leicester. Shakespeare also used Hall as a source for his history plays.