In my last post I looked at how Shakespeare acquired his family’s coat of arms. It is set down in two drafts made on 20 October 1596, described as follows:

In my last post I looked at how Shakespeare acquired his family’s coat of arms. It is set down in two drafts made on 20 October 1596, described as follows:

The arms are blazoned. “Gold, on a bend sable, a spear of the first, steeled argent [a gold spear tipped with silver on a black diagonal bar]; and for his crest, or cognizaunce a falcon his wings displayed argent, standing on a wreath of his colours, and supporting a spear gold steeled as aforesaid, set upon a helmet with mantles and tassels as hath been accustomed”

Heraldry has its own language: Silver is argent, sable is black, and so on. Coats of arms often included witty visual references to people’s names, as in Shakespeare’s case where the spear is an obvious reference to the family name.

The College of Arms also had its own rules about who was and was not fit to be granted arms, hence the 1602 disagreement about Shakespeare’s arms. When two of the Heralds replied to the complaint, they stated that the spear was a “patible difference”, making the coat of arms unique. To the suggestion that the family was unworthy, they wrote that John Shakespeare had “borne magistracy and was Justice of the Peace at Stratford-upon-Avon,”, had married “the daughter and heir of Arden” and “was able to maintain that estate”.

I confess to knowing little about the subject and am grateful to heraldry expert William Collins for these details. He also comments that “In a period when many grants were of complicated coats of arms, the Shakespeare arms were simple, beautiful, and a good example of canting arms”. His work detailing all the heraldry to be found in Holy Trinity Church can be found in the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Once granted, how was the coat of arms used? The most prominent use is on the monument to Shakespeare above his grave in Holy Trinity Church. It’s worth noticing that while William Dugdale, in his 1656 History of Warwickshire, gets some of the details of the figure of Shakespeare wrong, the coat of arms is accurate. It also appears, quartered with other arms, on some of the family gravestones: John and Susanna Hall, and their son-in-law Thomas Nash. None of these show the quartering with the arms of the Arden family.

Shakespeare’s coat of arms is also carved on a chair which has a fascinating history. Traditionally known as Shakespeare’s Courting Chair it was in Anne Hathaway’s Cottage in 1792 when it was purchased by Samuel Ireland from descendants of the original Hathaway family. He was told that the chair had been passed down to Shakespeare’s grand-daughter who passed it to them. Ireland published an illustration of the chair showing the coat of arms but not the carved initials WAS (William and Anne Shakespeare). After its purchase the chair disappeared for over 200 years, unexpectedly turning up in an auction in 2002 when it was returned to Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, where it can still be seen. I’m indebted to Ann Donnelly, former Museum Curator for the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, for the following: “we had the layers of patina, taken from strategic points on the chair and carvings, analysed microscopically. It wasn’t conclusive, but it was suggestive that the two elements of the arms, the shield and falcon, were roughly contemporaneous with the making of the chair itself. They are cruder than the cresting and carving on the stiles of the back of the chair, and were maybe added slightly later”.

Furniture expert Victor Chinnery suggested the style of the chair was appropriate for a date in the early to mid 1600s. We can’t know if it was Shakespeare’s chair but it certainly dates from his own lifetime or soon afterwards.

Ben Jonson was obviously amused by Shakespeare’s enthusiasm to join the gentry. A motto accompanied the coat of arms, “Non sanz droict” or “Not without Right” and in Jonson’s 1599 play Every Man Out of his Humour, the character Sogliardo’s motto is “Not without Mustard”. I wonder if Shakespeare saw the joke. He doesn’t ever seem to have used the motto.

Pericles presenting his arms to Thaisa in the Shakespeare Theatre Company's 2007 production of Pericles

It seems though that he wrote other mottos. It’s recorded that in 1613 Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland, ordered an “impresa”, an allegorical device, with a motto, from Shakespeare, which the actor Richard Burbage painted onto a paper shield. The record of the payment, 44 shillings, still exists, but rather typically the design itself is lost. The Earl then carried the shield at a tournament to celebrate the anniversary of the King’s Accession on 24 March. This sort of occasion is described in Pericles, where several knights appear bearing heraldic emblems and devices, including:

A burning torch that’s turned upside down:

The word: “Qui me alit me entinguit”.

Which shows that Beauty hath his power and will,

Which can as well enflame as it can kill.

The scene was probably written by George Wilkins, the play’s co-author, but Shakespeare would have known it.

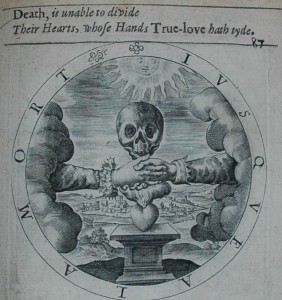

The devices are reminiscent of the puzzling images that accompany verses in emblems books like Wither’s Emblemes, published in 1635 but using illustrations from 1610-1613. Like the art of heraldry itself these mysterious but beautiful images demand special knowledge in order to unlock their meaning.

Hi Sylvia,

I found this article today. DO you know of any evidence for the Hart family moving to Australia?

http://www.themercury.com.au/article/2011/11/08/274941_tasmania-news.html

yours

William

Hi William,

Descendants of Joan Hart are certainly alive today. I believe that some of them did emigrate many years ago, but off the top of the head I don’t know where they went, though Australia sounds right. I haven’t been able to access the webpage, unfortunately. If you contact the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive at http://www.shakespeare.org.com and ask them to check an item in their holdings, DR1185 this family tree shows all the branches of the family.

Best wishes and keep enjoying the blog!