In his latest blog post, Stanley Wells has picked up on Michael Billington’s tweet about The Taming of the Shrew. Was he right, the critic asked, to suggest some thirty years ago that this play should be banned?

How time has moved on. The audience for the current RSC production, which is about to go on tour, express their enjoyment noisily. It’s a confident, brash production that makes the most of the play’s potential for slapstick, and of the attractiveness of Kate and Petruchio. On first seeing Kate, Petruchio turns to the audience and mouths “wow”. He strips to the waist for his wedding. Their onstage wrestling will inevitably lead them under the stage-size duvet, and it’s just a question of how long it takes them to get there. As Professor Wells notes, the production is made more palateable by the relish brought to the extended induction, the play becoming Christopher Sly’s vulgar dream.

More seriously, the play provides directors of Shakespeare with a tricky challenge. How can it be explained that the man who wrote with such tenderness in Romeo and Juliet could write a scene where a man humiliates his new wife in front of her own family?

She is my goods, my chattels, she is my house,

My household stuff, my field, my barn,

My horse, my ox, my ass, my any thing.

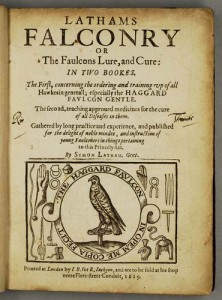

Petruchio’s sentiments are appalling, but in the second he explains his plan. He will tame Kate by following the advice of books like Latham’s Falconry, depriving her of sleep and food as he would a bird of prey. This also sounds distasteful, but in the many other versions of this story the husband always resorts to wife-beating. Kate and Petruchio often fight in productions, but Shakespeare doesn’t require Petruchio to strike Kate. He may be violent to his servant, but it’s Kate who ties up her sister, who strikes her tutor, and who hits Petruchio.

In Shakespeare’s own time there were debates about whether it was lawful for a man to beat his wife, and W Whately, in The Bride Bush, 1617, suggested women should accept that “mine husband is my superior, my better: he hath authority and rule over me; nature hath given it to him… God hath given it to him”.

In 1978/9 Michael Bogdanov, in a landark RSC production, still saw Petruchio wrestle his Kate to the ground in their first scene together. Perhaps it was this that made Billington label the play “totally offensive” on his first viewing. Another critic, Benedict Nightingale, saw that Bogdanov had uncovered a “secret play” which Shakespeare had hidden “inside the official one”, the production attempting to decode Shakespeare’s subversive message about sexual equality. This may be endowing Shakespeare with too much modern sensitivity, but Bogdanov certainly ensured that Katherina’s final speech was highly charged.

David Suchet as Grumio, Paola Dionisotti as Kate, Jonathan Pryce as Petruchio admiring the sun (or the moon)

Let’s rewind a bit, to Act 4 Scene 5, the scene where Petruchio insists the sun is the moon, and vice-versa, and their next scene, in which he asks her for a kiss. Kate has learned that life is not just easier, but more fun, if she is in Petruchio’s team. She calls him “love”. Paola Dionisotti, in Carol Rutter’s book Clamorous Voices says “Suddenly, everything was possible. I used to feel, ‘I think I know what game I’m playing. I think it will be all right. I think I can actually enjoy this’. ” But what about Petruchio?

When the production got to London, it was reviewed again, and Billington saw it differently. “Before, it looked as if a brutal Petruchio was gratuitously tormenting a high-spirited but not unamiable Kate. I now see that this production is entirely about the taming of Petruchio”.

The master stroke of the final scene was indeed about Petruchio, who had failed to learn when to stop. By making her obedience the subject of a conventional bet with other men, he had gone too far. Paola Dionisotti again: “He makes the mistake of encouraging me to say something. So I say it all”. During her lengthy speech, Jonathan Pryce exhibited more and more discomfort. Billington: “Confronted with the logic of his own actions, he quails: and when she ventures to kiss his shoe, he instantly withdraws his foot”.

Paola Dionisotti describes the same moment: “My Kate was kneeling and I reached over to kiss his foot and he gasped, recoiled, jumped back, because somehow he’s completely blown it. He’s as trapped now by society as she was in the beginning. Somewhere he’s an okay guy, but it’s too late. “

Instead of the passionate coupling of the current production, the two protagonists left the stage as lonely individuals. There was little whooping, but it was a production the audience did not forget.

Just a comment on Latham’s Falconry. I’ve spent a lot of time studying Shakespeare and falconry references (as a passionate lover of both) and have recently completed a commentary upon, and facsimile of, Latham’s works for the edification of falconers (we’re mostly an unlettered lot). Latham would have found starvation and “waking” pretty poor practices for training a hawk – indeed much of his first book details how to condition a falcon for strong flight (essential for successful hawking) by provoking a robust digestive system without reducing her will or strength: a starved hawk of falcon was, and is, a terrible indictment of a second rate keeper who doesn’t deserve to be called “falconer.”

I mention this not so much to defend my 400 year-old “co-author” but since I believe that Shakespeare was sufficiently well acquainted with the intricacies of falconry to have realised that the successful falconer would not resort to such coarse and primitive methods, even in the case of the “haggard” falcon like Kate. Falconry has always made such a good analogy for love because of the contradiction that one must take a wild creature (at least, back then, when wild-taken falcons were the norm unlike modern day British practice) and confine her, but then release her to return if she so wished, or return to her former lifestyle otherwise. The falconer knows that a falcon deprived of her freedom isn’t really a falcon: a case of “if you love someone, set them free”?

It may well be that in showing Petruchio resorting to such tactics (and his pun on “Kate” and “Kites” – the latter an ignoble species to the contemporary practitioner, and as carrion eaters totally useless for falconry – underlines this) Shakespeare is showing him to be an unsuitable candidate for the sport – a hawk keeper, yes, but not a falconer. Might this then tally with the idea that Shakespeare had more modern-leaning sensibilities? I suspect so, based on his use of falconry here. Indeed, the “sequel” to “Taming of the Shrew” (“The Woman’s Prize, or the Tamer Tamed”) by Beaumont and Fletcher makes clever use of detailed falconry knowledge to show the falcon’s viewpoint, as I explore in “Falconry in Literature” which covers references in Renaissance literature. Interesting that Sir Henry Herbert (Master of Revels under Charles I) clamped down on the latter play for its “offensive” nature which reflected a world turned upside down to patriarchal views of society – as in Brome’s “The Antipodes” which similarly uses hawking imagery where the quarry chases the hawks, and women go out to work whilst men stay at home.

“Taming” is perhaps one in a long list of literary allusions to falconry which demonstrate something of a role reversal to the contemporary views of society. Lovelace’s “A Lady wth a Falcon on Her Fist” similarly challenges male stereotypes. Perhaps an aside in the greater picture of literary/stage criticism, but one which I’d recommend scholars and lovers of Shakespeare to look into: it gives a fascinating insight into the contemporary mindset where those “in the know” regarding the subtleties of hawks and hawking (and perhaps of human relationships?) maybe saw things somewhat differently to the way in which 21st century commentators, based on misconceptions of falconry, might expect.