While browsing in Michael Wood’s book In Search of Shakespeare I found one of those possible Shakespeare references that you’d just love to be true.

It relates to the Jesuit Robert Southwell. Born and brought up in England, he first went to the continent to pursue his religious studies aged only 15, and after several years in France and Italy returned in 1586 aged about 25. Catholic priests were outlawed and he knew that detection would mean death: he embraced the idea of dying a martyr.

For six years he moved from safe house to safe house, including a time at Baddesley Clinton near Stratford, where he narrowly avoided capture. It’s still possible to see the priest’s hole where he hid. His luck ran out in 1592 when he was captured. Over the next three years he was tortured and imprisoned in the Tower of London, then prosecuted for treason and brutally executed on 20 February 1595.

What set Southwell apart was that he was an accomplished poet writing on religious themes. It sounds unlikely given the persecution of Catholics, but some of his writings were published during his lifetime and others were circulated in manuscript. After his death, more work was published, and proved popular for several decades. Thomas Nashe imitated some of his poems proving that their merit was recognised outside Catholic circles, and Ben Jonson was a great admirer of his work.

As well as writing poetry himself, Southwell also wrote about the purpose of poetry, which he maintained should be written to the glory of God. He wrote that most poets “have wedded their wills” to “unworthy affections”, that is, worldly love. Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis was exactly the sort of poem he most wished to supplant, and there are clues that indicate that he knew the poem, which he must have read in prison, where he also did much of his writing.

His most famous poem, The Burning Babe, was published in a collection in 1595, the same year he died. Shakespeare refers to this poem in Macbeth. In Act 1 Scene 7, Macbeth is persuading himself not to murder the virtuous Duncan. He speaks about how Pity, in the form of a baby, would condemn the deed:

And Pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heaven’s Cherubins, hors’d

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That tears shall drown the wind.

This inexplicable image begins to make sense when Southwell’s poem is read. It refers to the nativity of Christ, born to be a sacrifice to mankind.

A pretty babe all burning bright did in the air appear;

Who, though scorched with excessive heat, such floods of tears did shed,

As though his floods should quench his flames, which with his tears were fed.

The full text of the poem is here.

More recently it’s been suggested that another poem by Southwell is an even closer match to Shakespeare’s speech. The poem is called New heaven, new warre, and again Christ is likened to a newly-born baby, fighting the battle for men’s souls. Here is one stanza:

With teares he fights and wins the field,

His naked breast stands for a shield,

His battering shot are babish cryes,

His Arrowes looks of weeping eyes,

His Martial ensignes colde and neede,

And feeble flesh his warriers steede.

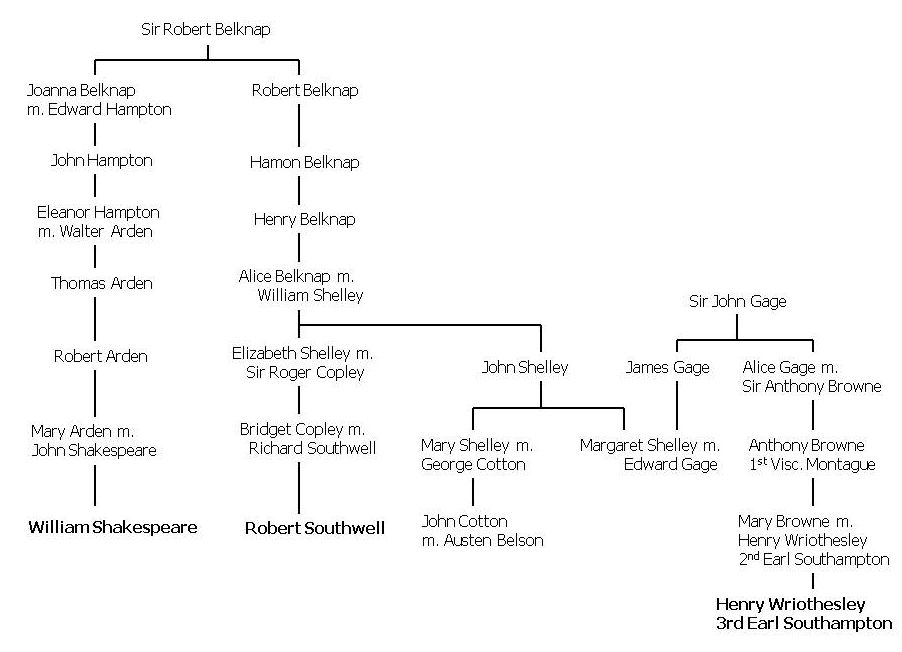

Michael Wood, though, highlights a more mysterious connection between them. It seems that Shakespeare, Southwell and the Earl of Southampton were all distantly related, sufficiently, according to Wood, for Southwell to address William as “cousin”.

One of Southwell’s works was entitled St Peter’s Complaint, a collection of religious poetry to which he wrote a preface directly criticising modern poets:

One of Southwell’s works was entitled St Peter’s Complaint, a collection of religious poetry to which he wrote a preface directly criticising modern poets:

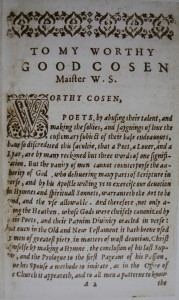

Worthy cosen, Poets, by abusing their talent, and making the follies, and faygnings of love the customary subject of their base endeavours, have so discredited this facultie, that a Poet, a Lover and a Lyar, are by many reckoned but three words of one signification.

On the title page, the letter is addressed “To my worthy good cosen”. It was published after Southwell’s death in 1595, but had circulated in manuscript for some years before that. Southwell’s poems were popular, and St Peter’s Complaint was republished in 1616. On this title page, the address is “to my worthy good cosen Maister W. S.”. Shakespeare died in 1616.

On the title page, the letter is addressed “To my worthy good cosen”. It was published after Southwell’s death in 1595, but had circulated in manuscript for some years before that. Southwell’s poems were popular, and St Peter’s Complaint was republished in 1616. On this title page, the address is “to my worthy good cosen Maister W. S.”. Shakespeare died in 1616.

What are we to make of this? Scholars have tried unsuccessfully to find another relative of Southwell’s with the initials WS. And why the change in 1616? Was it to protect Shakespeare while he lived? More than twenty years after the death of Southwell, who was to know, and who took the decision to change the title page?

We’ll probably never know. In his book Wood emphasises any evidence that implies Shakespeare could have been a Catholic, and it’s possible that this is pure wishful thinking. What is certain, though, is that Shakespeare knew Southwell’s poetry, and Southwell almost certainly knew his. While he may have disapproved of the subject matter, he must have admired the skill.

‘The Burning Babe’ was part of a poetry collection set for my ‘A’ Level syllabus more years ago than I care to remember now, however, I do still remember the poem which says something about its force. I hadn’t thought to make the link with ‘Macbeth’ but reading this I can see why you might do that. I tend to cast a sceptical eye over theories that push the catholic connection too hard as they often appear to have an agenda other than discovering the facts. Perhaps it is enough to say that this poem was out there in the general literary ether at the time. Shakespeare was clearly a ‘snapper-up of unconsidered literary trifles’ let alone something of this merit.