October is Black History month, and this year’s focus on Shakespeare has included a number of discussions of the presence of non-white people in England in the early modern period.

Historian Michael Wood’s piece suggests there was a black community in London, using evidence from the parish registers of St Botolph’s without Aldgate which show that black people lived as servants and workers in the capital, sometimes marrying native English people. John Blanke was a trumpeter who played for Kings Henry VII and VIII, a black face among the ceremonial musicians in the illustration dating from 1511.

There’s evidence that these people either had difficulty integrating, or were discouraged from doing so. Towards the end of the period proclamations were issued requiring native Africans to be repatriated owing to their being too many of them in the capital (though there is no evidence to suggest this was ever carried out). Wood quotes from Cecil’s 1601 papers, still kept at Hatfield House:

The queen is discontented at the great numbers of ‘negars and blackamoores’ which are crept into the realm since the troubles between her Highness and the King of Spain, and are fostered here to the annoyance of her own people.

It’s thought these people had been captured from Spanish ships, and although they were mostly employed as servants they must have been seen by Shakespeare in London. But it wasn’t these people that Shakespeare put into his plays: his black characters are powerful or aristocratic, maybe both. Think Othello, Aaron in Titus Andronicus, and the Prince of Morocco in The Merchant of Venice.

It’s thought these people had been captured from Spanish ships, and although they were mostly employed as servants they must have been seen by Shakespeare in London. But it wasn’t these people that Shakespeare put into his plays: his black characters are powerful or aristocratic, maybe both. Think Othello, Aaron in Titus Andronicus, and the Prince of Morocco in The Merchant of Venice.

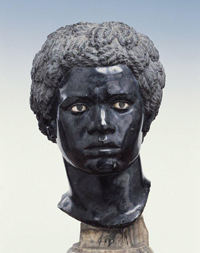

In the British Museum’s current Shakespeare: staging the world exhibition some of the most striking exhibits are the artistic representations of blacks though most, like the one illustrated, are not English. This one was made in Rome around 1610.

But the most impressive visitation of black Africans during the time Shakespeare lived in London was the 1600 arrival of the Moroccan Ambassador and his 16-strong entourage. Their aim was to undertake preliminary talks with the hope of forming an alliance between the two countries against Spain. The intention was to take some of the East and West Indies back from Spain, and share the spoils. It’s recorded that they stayed in London for six months, being present for the festivities marking the anniversary of the Queen’s coronation on 17 November, but the hoped-for alliance never materialised.

While here, the ambassador Abd-el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun had his portrait painted in his robes and magnificent sword. It’s unthinkable that Shakespeare didn’t see this man, and it’s tempting to see in him the prototype for Othello. The painting is part of the British Museum’s exhibition until the end of November, but usually hangs in the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Elsewhere in the country other non-white faces were seen. The adventurers Sir Richard Grenville and Sir Walter Raleigh were involved in the attempts to found a settlement in Virginia and made a number of visits there. On one of these, in 1586, it was later reported by Pedro Diaz that Grenville captured several native Americans. Most escaped, but one was brought back to his home town of Bideford in North Devon where he became Grenville’s servant. Diaz’s account explains the otherwise puzzling entries in the parish register for St Mary’s Church: on 26 March 1588 “Raleigh, a Winganditoian” was baptised, and in April 1589 the same man, described as “Rawley, a Winganditoian” was buried. Nothing else is known about him: one story suggests he died of a cold, another of homesickness. Whatever the truth, his must have been a lonely existence. He is believed to be the first Native American to be baptised in England.