A couple of weeks ago David Frankel from the University of South Florida put an enquiry onto the Shakespeare noticeboard site SHAKSPER asking if anyone knew when the term “Bard of Avon” was first applied to Shakespeare. I replied with a couple of examples of similar though not identical phrases which were used as part of the Shakespeare Jubilee, and written by David Garrick. These were the earliest I was aware of, but had a sneaking feeling that there must be an earlier reference.

Sure enough, such is the magic of SHAKSPER, that someone found a reference to “Bard of Avon” in the article written by John Gilbert Cooper Cursory remarks on Mr. Warburton’s new edition of Mr. Pope’s works: Occasioned by that modern commentator’s injurious treatment, … of the author of the life of Socrates. …

The quote reads:”I suppose it was upon the same conscientious Principle, that, during this charitable Delay, he busied himself in making new and revising his old Notes upon the immortal Bard of Avon;” . This was published in 1751, 18 years before the Garrick Jubilee.

There was obviously a story here: who was John Gilbert Cooper, and what did Mr Warburton have to do with it? I knew of the eighteenth century edition of Shakespeare edited by Pope and Warburton, but not a lot more.

Before the dramatist Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition there were only four large and unwieldy Folio editions, and individual plays in Quarto. Rowe’s edition included a biography of Shakespeare and an illustration for each play. His edition was also the first which could be comfortably held in the hand to read.

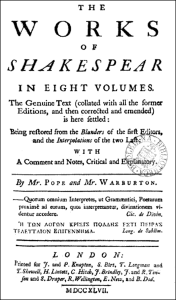

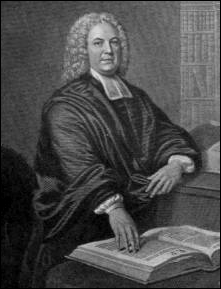

The occupation “textual editor” didn’t exist at the time, and following Rowe’s lead a number of others had a go themselves. First was Alexander Pope, a celebrated poet who by changing words and rewriting phrases gave Shakespeare’s energetic lines polish, though with little regard to scholarship. His 1725 edition was full of errors and the following year the scholarly Lewis Theobald published corrections to it under the title Shakespeare Restored. Pope’s second edition silently incorporated Theobald’s corrections. Theobald published his own edition in 1733. William Warburton, a young Lincolnshire clergyman, supported Theobald, later changing his allegiance to support Pope. Theobald, the first great Shakespeare editor, was thus denigrated even while his critics plundered his work.

A further edition of the plays was produced in 1744, by Thomas Hanmer, made popular by its beautiful illustrations. Both Theobald and Pope died in this year, and Hanmer died in 1746, leaving Warburton clear to publish his own edition being as critical as he liked of his rivals. His edition, in which he acknowledged Pope on the title page, came out in 1747. Warburton was Pope’s literary executor and he also published a complete edition of Pope’s works.

The young John Gilbert Cooper stumbled into this bad-tempered controversy. He was born in Leicestershire in 1722 to a comfortable family as John Gilbert, but on inheriting the land and house of John Cooper of Thurgarton Priory in Nottinghamshire his father took the additional name of Cooper. Young John was educated in Sutton Coldfield, Westminster and Cambridge. His first poetry was published in 1742, and his criticisms of the established Warburton resulted in that author’s retaliation, which in turn provoked Cooper’s Cursory Remarks in 1751. Their argument was commented on by the famous writer who would later publish his own edition of Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson.

Cooper continued to write poetry, some of which has considerable charm. One of his last poems was The Tomb of Shakespeare: a vision. In this 1755 poem he describes the setting of Holy Trinity Church.

On Avon’s banks I lit, whose streams appear

To wind with eddies fond round Shakespeare’s tomb.

The year’s first feathery songsters warble near,

And violets breathe, and earliest roses bloom.

Shakespeare’s burial place is, he observes, Fancy’s “fav’rite offspring’s long and last abode”. He asks the figure of Fancy to show him Shakespeare’s most imaginative creations. She conjures visions of Ariel and Caliban from The Tempest, Titania and Oberon from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the Witches in Macbeth. Here is the description of Ariel:

He whirled the tempest thro’ the howling air,

Rattled the dreadful thunderclap on high,

And raised a roaring elemental war

Betwixt the sea-green waves and azure sky.

John Gilbert Cooper had no need to work, but his life was not untouched by tragedy. He married in 1748. His first child died soon after birth, and his wife died seven weeks after giving birth to their third child in 1751, leaving him the father of two babies. He died himself in 1769, aged only 47, just months before the Garrick Jubilee, and is buried at Thurgarton.