Newspapers are a relatively new invention: no character in a Shakespeare play ever reads one, news being conveyed by messenger or letter. In The Merchant of Venice Tubal brings a personal account to Shylock of the misfortunes of Antonio’s ship “I spoke with some of the sailors that escaped the wrack”, and later a letter from Antonio to Bassanio brings the bad news. Bassanio quizzes the messenger for more information:

But is it true, Salerio?

Hath all his ventures failed? What, not one hit?

From Tripolis, from Mexico and England,

From Lisbon, Barbary and India,

And not one vessel scape the dreadful touch

Of merchant-marring rocks?

Elsewhere news is spread by rumour, brought to life “painted full of tongues” at the beginning of Henry IV Part 2.

Upon my tongues continual slanders ride,

The which in every language I pronounce,

Stuffing the ears of men with false reports.

The first news of the outcome of the Battle of Shrewsbury is brought to Northumberland, leading him to hope his son Hotspur has triumphed. These false hopes are quickly dashed by a second and third report, but it’s the eye-witness account that convinces: “These mine eyes saw him in bloody state”.

No wonder the relatives of passengers on the Malaysian Airlines plane that disappeared over the southern Indian Ocean are struggling to come to terms with their loss, without any evidence of the fate of the place let alone an eye-witness account.

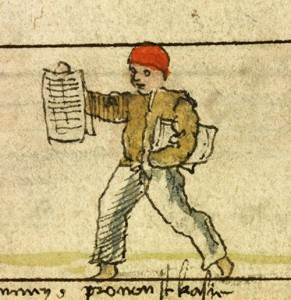

We have become used to seeing visual evidence of catastrophic events, but the humble newspaper has been our method of getting news of events beyond our own experience for centuries. Before newspapers there were broadsheets, and the illustration above is from the Cambrai Chansonnier, a manuscript song-book created for a wealthy inhabitant of Bruges, dated 1542. The picture has informally been called “The first paper boy”.

In England it took a while for newspapers proper to emerge. The first London newspaper, the Corante, was published in 1621, but the first regular daily newspaper, the Daily Courant, dates from 1702. If you’d like to follow it up there’s a history of papers here.

Governments attempted to prevent information being made widely available, putting a tax on newspapers in 1712. Inevitably people found ways of getting round it, by clubbing together, hiring a paper for an hour or visiting an alehouse which kept newspapers, even old ones. But the tax did restrict the number of newspapers published. This situation continued until 1855 when the law was changed to reduce this tax, and papers that cost 4d each became available for 1d. Newspapers were suddenly affordable and smaller places were able to print their own. Before 1860 Stratfordians had to rely on papers with a larger geographical coverage: between 1806 and 1860 The Warwickshire Advertiser was the nearest thing there was to a local newspaper. Then came the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald which is still published today and an enormously valuable resource for anyone studying the history of the town. Here’s an article on the subject.

For many years the Newspaper Library at Colindale, in London, was the place to go for British Newspapers. But no more, as it closed in November 2103. Now the newspapers are being transferred to a new location:

The NSB, or Newspaper Storage Building, is the British Library’s new home for newspapers. Situated at our second site in Boston Spa, Yorkshire, it is not where users will be able to read our print newspapers – that will be in the Newsroom at St Pancras, when they become available once more in Autumn 2014 – but it is where they are starting to be stored, in optimum preservation conditions.

A condition report found that the newspapers are some of the most fragile and threatened items held by the British Library, and no wonder, since they have never been intended for long-term keeping, and their large size often makes them difficult to handle. There is another post here about how they are preserving the originals while making microfilm or digital copies available for use.

The new building, however, is almost scarily high-tech. The NSB is completely automated:

It is essential for the long-term preservation of the print newspapers that they be kept at optimum temperature and humidity-controlled conditions, and in the dark. Inside the NSB the temperature is being maintained at 14⁰C, with relative humidity at 55%, and the oxygen level 14-15%, eliminating any risk of fire. So it is great for newspapers, but not so great for humans. Instead the process of ingest, shelving and retrievable is all undertaken by fully-automated machinery – appropriately robotic for a spaceship. – See more at: http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/thenewsroom/2014/03/checking-out-the-nsb.html#sthash.cwaH1CJ1.dpuf

It will still be possible to go an read the originals at the British Library itself, and there’s a guide here.

In addition there are ambitious plans to digitise the millions of pages of newsprint, making them available for all at the British Newspaper Archive site.

Access to the site has to be paid for, but for most the convenience of having the newspapers available on their desktops will be easily preferable to making a trip to the Library. And even more people will be able to explore what’s often been called “the first rough draft of history”.

You can’t always believe what it says in a newspaper though!! See the following, printed in the Midweek Stratford Herald on Tuesday April 1st.

http://www.stratford-herald.com/local-news/7964-unbeliveable-shakespeare-find-at-his-school.html

What an extraordinary building that new BL newspaper storage is!

Jo is quite right, although that particular story was meant as an April fool joke. Unfortunately journalism doesn’t require the same exacting accuracy as history and can be misleading sometimes even deliberately inaccurate.