President Obama is about to hand over to the incoming President Trump, and in the last few days an interview with Obama about the books that are important to him has been published in the New York Times. One of the authors he mentions is of course Shakespeare.

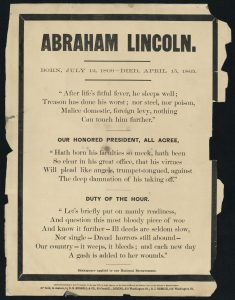

President Obama has not made it a habit to quote from Shakespeare in his speeches, unlike his predecessor President Lincoln, who Obama has often mentioned as a source of inspiration. Lincoln was so closely associated with Shakespeare that after his death in April 1865 this document “Shakespeare applied to our national bereavement” was published quoting from Macbeth, in particular the murder of Duncan.

Many presidents have been influenced by Shakespeare and his interest in politics, as this essay that appears on the White House Historical Association’s site shows, and I have cited before this section from the Folger Shakespeare Library that includes a piece on how many US presidents owed ideas or quotations to Shakespeare.

My blog post on early American visitors to Stratford included the visit of two Presidents-to-be who came a pilgrimage to visit the Birthplace in the astonishingly early year of 1786. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were the men.

President Obama may not have come to Stratford-upon-Avon, but during his visit to the UK in April of 2016 when the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death was being marked he visited Shakespeare’s Globe in London, where, among tight security, they staged a medley of scenes from Hamlet specially for him.

It seems unlikely that the new occupant of the White House will be reading, or quoting, much Shakespeare over the next four years, but Shakespeare will still remain relevant. The Shakespeare play most appropriate for the political situation we find ourselves in at the start of 2017 seems to be Coriolanus, though the parallels are complex. Even written for a very different world, four hundred years ago, Shakespeare brings out those similarities, and a production of the play in New York just before the election in succeeded in reflecting the concerns of many in the USA. It isn’t just the interplay of Coriolanus, Aufidius, and those Roman tribunes, but Menenius’s speech about the belly’s place in the body as a metaphor for a political system, that strikes a chord.

There was a time when all the body’s members

Rebell’d against the belly, thus accused it:

That only like a gulf it did remain

I’ the midst o’ the body, idle and unactive,

Still cupboarding the viand, never bearing

Like labour with the rest, where the other instruments

Did see and hear, devise, instruct, walk, feel,

And, mutually participate, did minister

Unto the appetite and affection common

Of the whole body…

The belly responded:

‘True is it, my incorporate friends,’ quoth he,

‘That I receive the general food at first,

Which you do live upon; and fit it is,

Because I am the store-house and the shop

Of the whole body: but, if you do remember,

I send it through the rivers of your blood,

Even to the court, the heart, to the seat o’ the brain;

And, through the cranks and offices of man,

The strongest nerves and small inferior veins

From me receive that natural competency

Whereby they live:…

Though all at once cannot

See what I do deliver out to each,

Yet I can make my audit up, that all

From me do back receive the flour of all,

And leave me but the bran.’ …

The senators of Rome are this good belly,

And you the mutinous members; for examine

Their counsels and their cares, digest things rightly

Touching the weal o’ the common, you shall find

No public benefit which you receive

But it proceeds or comes from them to you

And no way from yourselves.

Whatever happens next, it seems certain that Shakespeare will already have written about it.