8 March 2017 is both the UK’s Budget Day and International Women’s Day, when attention is drawn to gender inequality in all fields including education and jobs. In addition, demonstrations will be held at Westminster by WASPI campaigners fighting for the pension rights of women suffering from a lack of transitional arrangements to cover changes in their retirement age.

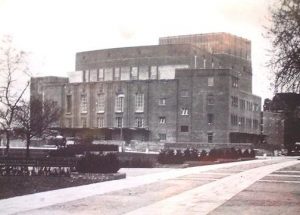

Equality may not yet have been achieved, but in Stratford-upon-Avon stands one of the most obvious manifestations of women’s entry into the professional world in the early twentieth century. The Royal Shakespeare Theatre (formerly the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre), although much changed by the transformation project completed in 2011, was designed by a woman, Elisabeth Scott. Following the disastrous fire of 1926 a competition was held for a new design, and the resulting theatre was opened in 1932. The Builder pointed out that “this was the first important work erected in this country from the designs of a woman architect”, and The Lady suggested “Miss Scott’s theatre will stand as a landmark in the professional and artistic achievements of women”. Not only was Elisabeth Scott a woman, she was a young woman, and at the time she entered the competition she was still too young to vote. Women only gained equality with men in 1928 when the voting age for women was lowered from 30 to 21.

Scott was related to Sir George Gilbert Scott, the designer of London’s St Pancras Station, but she was also a qualified architect, having spent five years studying for her Architectural Association diploma. She worked for Maurice Chesterton’s architectural firm in London and colleagues collaborated with her on developing her ideas. The location, where all four sides of the theatre would be visible, made it particularly challenging. “The Stratford site offers difficulties and opportunities” she said at the time.

In accepting the award she stated:

I belong to the modernist school of architects. By that I mean I believe the function of the building to be the most important thing to be considered. In terms of theatre…this means…that acoustics and sight lines must come first…At the same time I have taken full advantage of the exceptionally beautiful site on the banks of the Avon.

For the assessors, her design had won because it had “a largeness and simpleness of handling which no other design possesses. The general silhouette and modelling to fit the lines of the river are picturesque and the character of the design shows consideration for the locality”.

After winning the award she spent a year developing detailed plans, visiting theatres in other countries with the theatre’s Director William Bridges-Adams and Archibald Flower, Chairman of the Theatre’s Governors. Bridges-Adams explained “The need is for absolute flexibility, it should be, so to speak, a box of tricks out of which the childlike mind of the producer may create what shape it pleases”, not the clearest guidelines for an architect called on to make decisions as work progressed. The Governors of the theatre meanwhile brought in experts in theatrical equipment, stage designers, acoustics and electrics. Some of Scott’s original ideas were abandoned, and many changes were made for financial rather than artistic reasons. There was inevitably an air of disappointment when the theatre opened. When it came to performing, actors felt cut off from audiences and audibility was a major problem, though sight-lines were good with most of the audience directly facing the stage.

They may have said that “nothing but the best is good enough for Shakespeare” but in spite of, or perhaps because of, the amount of advice offered, the theatre was far from perfect. Writing in 1993, Iain Mackintosh suggested that while Elisabeth Scott thought she had created a focused intimate theatre, she had not. “The theatrical profession, when roused, is more vociferous than the architectural profession and the nation accepted the theatrical view: it was all the fault of the architect. It is clear that there had been a breakdown in communication between the two professions”.

There were many attempts to remedy the situation, and the transformation of the last 10 years has now completely changed the auditorium, altering the actor/audience relationship and making the theatre much more intimate.

The modernist exterior had both admirers and critics, but many of the beautifully-crafted details such as the richly-decorated doors, the spacious foyer and the spiral staircase with its marble fountain (designed by another woman, Gertrude Hermes) were often remarked on and have been enjoyed by generations of theatre-goers.

The theatre building is its own memorial to Elisabeth Scott as the heart of her theatre remains. So important is she seen to be that an image of her, and the theatre she designed, now graces the United Kingdom passport. But it seems to me a pity that there is no acknowledgement to her within the theatre, nor to the part she played in establishing the role of women in the workplace.

NB The quotations, and many of the details in this post are taken from Marian J Pringle’s book The Theatres of Stratford-upon-Avon 1875-1992, published by the Stratford-upon-Avon Society, 1994.