People have been trying to identify Shakespeare’s Dark Lady, the mysterious woman who is the subject of some of Shakespeare’s sonnets, since the Victorian period. A few years ago Emilia Lanier was the favoured candidate, and before that Mary Fitton. A couple of new books (one not yet published but already making waves) suggest different candidates.

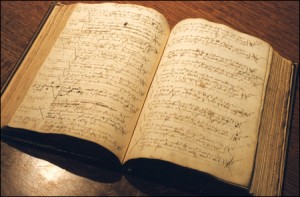

Duncan Salkeld’s Shakespeare among the Courtesans will be published in October, but it’s already suggested that he’s found some new evidence to support the identity of Black Luce, or Lucy Negro, who ran a brothel in Clerkenwell, as Shakespeare’s Dark Lady. Her associate Gilbert East (who ran another brothel) is possibly mentioned in Philip Henslowe’s Diary, a document which contains information about playhouses inLondon particularly during the early years of Shakespeare’s writing career. “Lewce East”, perhaps a conflation of the two names (?) is listed as a tenant of the Boar’s Head in 1604. Here, courtesy of Dr Grace Ioppolo and the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project, is the page from the diary.

Dr Salkeld said “To my knowledge, no one has spotted this connection before.” He added: “Whoever that person was, Shakespeare painted her with the reputation of Luce… This is new evidence.”. It’s not a new association though: Dr Burl notes that G B Harrison made the connection in the 1920s.

That the Dark Lady might have been a prostitute isn’t entirely unlikely, no matter how unpopular the suggestion: Shakespeare described her as “my female evil” and “my bad angel”. Black Luce was described by contemporaries as “an arrant whore and a bawde’, who had everyone from “ingraunts” (immigrants) to “welthyemen” as customers. We’ll all have to see what else Dr Salkeld has unearthed when the book is published.

Aubrey Burl’s book Shakespeare’s Mistress is already published by Amberley Press. Dr Burl is a historian and archaeologist, and with a full bibliography and notes I was hoping for a well-argued case.

Aubrey Burl’s book Shakespeare’s Mistress is already published by Amberley Press. Dr Burl is a historian and archaeologist, and with a full bibliography and notes I was hoping for a well-argued case.

Burl’s approach is certainly unusual. He looks at the history of the literature about the dark lady, and picks eight of the existing candidates. For each one he reviews the opinions of those authors who have sided with the lady. His line-up is Jacqueline Field, Mrs Florio, Emilia Lanier, Lucy Morgan, Penelope Devereux, Mary Fitton, Mrs Marie Mountjoy and Mrs Jane Davenant. Some of these are the usual suspects, and range from prostitutes to respectable married women and even the nobility. To begin with I wondered if Dr Burl was going to suggest that Shakespeare had serial mistresses, over perhaps a twenty-year period. That would have been new! But after a very limited amount of debate, he favours Mrs Florio, the wife of the Italian John Florio, as his best guess.

We know next to nothing about Mrs Florio, not even her first name. Dr Burl suggests that she and Shakespeare met at Titchfield, The Earl of Southampton’s country house, though Florio and Southampton both had houses inLondon. Dr Burl talks about the importance of “considering the reliable evidence”, but falls into the trap of letting his imagination run away with him:

Shakespeare had been infatuated from the time when he first saw her. His eyes were drawn to her as she walked by him, rather quickly but with elegance. Usually, being a respectable married woman, she did not acknowledge him but sometimes she smiled, said a word or two before passing by.

There’s also a lot of repetition, and although not every book needs to break new ground Dr Burl relies very heavily on the opinions of other scholars. He mentions that Mrs Florio is Jonathan Bate’s candidate for Dark Lady, so I checked on what he has to say in The Genius of Shakespeare. Bate does indeed talk about Mrs Florio, though the “story is and is not a fantasy”.

I was surprised to find Jonathan Bate plumping for a real dark lady: academics usually steer clear of the subject, restricting comments to a discussion of the poetry. But although “I began to work on the sonnets with a determination to adhere to an agnostic position on the question of their autobiographical elements”, Bate found that the sonnets “wrought their magic”, and against his better judgement he became drawn in to the argument. He sees it as the genius of the poems that anyone who reads them cannot avoid being persuaded, at least in part, that theirs is a real story, populated with real people: the dark lady, fair youth, the rival poet, and the “I” of the writer.

If you want a summary of what’s been written about the Dark Lady of the sonnets, Dr Burl’s book supplies one. But I’d also suggest you read Jonathan Bate’s book for a consideration of the question about whether Shakespeare had a mistress at all.