I spent Saturday in Birmingham, at the Old Repertory Theatre in Station Street, which this year celebrates its centenary. A couple of weeks ago I wrote a blog about the history of Barry Jackson’s great theatre.

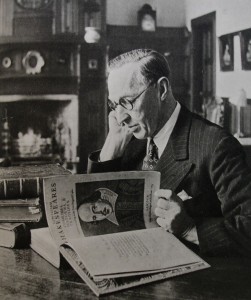

The keynote speech was given by actor and director John Harrison, whose career stretches back almost 70 years. He started his theatrical life at the Rep under Barry Jackson, being one of the first group of students in the Birmingham Rep School, for the training of actors, in 1943-4. He recalled that the tradition by which some leading actors still expected to be greeted with a round of applause, was still not dead, and Barry Jackson himself was treated with great formality, everybody calling him “Sir Barry”.

Love’s Labour’s Lost, 1946. David King-Wood as Berowne, Paul Stephenson as Ferdinand, Donald Sinden as Dumain and John Harrison as Longaville

Jackson was a shy man with a kindly and benign presence, and Harrison was obviously well-liked because he was one of just a few actors who made their way to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre when Jackson took over the reins there in 1946. Harrison took part in the 1946 and 1947 seasons, playing Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet and Longaville in Love’s Labour’s Lost, among other roles. I asked him about Dorothy Green’s production of Henry V, in which he had played the French Dauphin. Disappointingly, he said it had been one of the least successful productions of the 1946 season, Henry being Scofield’s least successful part. Scofield was one of the other actors who Jackson took with him to Stratford, having been immediately marked out for success on his arrival in Birmingham. Sullivan remembers Scofield’s stillness on stage: he said there was a connection between Scofield and the audience that marked him out as a star performer even at that young age.

He recalled how, during Peter Brook’s first rehearsal for Man and Superman Barry Jackson stood outside the rehearsal room door, so worried was he by Brook’s extreme youth. He was only 19, and at the time youth was not a recommendation, but Harrison and Scofield loved working with someone of their own generation. It was fascinating to hear John Harrison talking, he and Brook being what Roxana Silbert described as “the last survivors of that epic period”.

In the discussion that followed Barry Jackson’s career was mapped out by Claire Cochrane, who has documented the history of Birmingham Rep in two books, and by Peter Smith who talked about Jackson’s work forming the Malvern Festival: my own contribution was about the years from 1946-1948 when he was the Director of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Festivals. The session was chaired by eminent playwright David Edgar whose aunt, Nancy Burman, worked for Jackson as an administrator in both Birmingham and Stratford, through whom he met Jackson as a child.

In the afternoon we were treated to a showing of the 1986 film: Barry Jackson, The Quiet Pioneer, introduced by its maker Jim Berrow, by a talk about the Rep’s archives which I will be writing about in a later post, and a discussion with current practitioners and how classics can be made relevant to modern audiences. This was led by Roxana Silbert, the recently-appointed Director of the Birmingham Rep, writer Robin French, and designers Pamela Howard, Jamie Vartan and Ruari Murchison. Through this session the enthusiasm for theatre and for the creativity of the performing arts was palpable. The Old Rep, currently being used for the Rep’s performances while the New Rep is refurbished as part of the Library for Birmingham project, is clearly still a much-loved theatre that still works beautifully as a performance space. It’s where I first went to the theatre and saw my first Shakespeare productions, but it was also described by Pamela Howard as an Arthouse, where great visual artists like Paul Shelving worked. Barry Jackson himself was a designer as well as a director.

In the afternoon we were treated to a showing of the 1986 film: Barry Jackson, The Quiet Pioneer, introduced by its maker Jim Berrow, by a talk about the Rep’s archives which I will be writing about in a later post, and a discussion with current practitioners and how classics can be made relevant to modern audiences. This was led by Roxana Silbert, the recently-appointed Director of the Birmingham Rep, writer Robin French, and designers Pamela Howard, Jamie Vartan and Ruari Murchison. Through this session the enthusiasm for theatre and for the creativity of the performing arts was palpable. The Old Rep, currently being used for the Rep’s performances while the New Rep is refurbished as part of the Library for Birmingham project, is clearly still a much-loved theatre that still works beautifully as a performance space. It’s where I first went to the theatre and saw my first Shakespeare productions, but it was also described by Pamela Howard as an Arthouse, where great visual artists like Paul Shelving worked. Barry Jackson himself was a designer as well as a director.

It would be a tragedy for this historic theatre, still an effective performance space, to be neglected once the new Rep is reopened towards the end of the year. Serious theatre in Birmingham sometimes struggles to find an audience, but the world of theatre is still vibrant and indeed is one of the UK’s greatest assets.

Quite by chance, the Guardian has just published an article about the relationship between TV and theatre, pointing out that in the 1960s stage productions could inspire TV versions of classic plays. Yet now TV rarely goes back to stage plays, whether of Chekhov, or of contemporary work. One notable exception within the last twelve months has been Shakespeare, with the RSC’s Julius Caesar being adapted for the BBC, and a mini-series of history plays, The Hollow Crown. But the work of the young, exciting playwrights working in theatre is rarely considered. It would be wonderful if TV could be used to help build a new audience for contemporary theatre work, rather as the film of War Horse has benefitted the stage version.

Excellent point, Sylvia, re: more TV productions of modern/contemporary theatre like the fabulous “Hollow Crown” series. Hurray for cross-pollination.

As it happens my newest post is about the Hollow Crown series: I quite agree, cross-pollination works – and it isn’t always one-way!