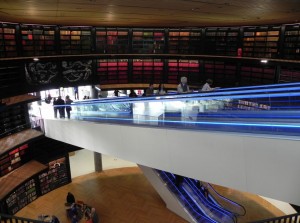

A week ago I went to take a first look at the new Library of Birmingham and its Shakespeare Memorial Room. I was a little apprehensive that it would have the appearance of a branch of Waterstones or even a shopping mall. But instead, I found a building that is both recognizably a library, but also a place buzzing with life. Here and here are links to a couple of reviews.

A week ago I went to take a first look at the new Library of Birmingham and its Shakespeare Memorial Room. I was a little apprehensive that it would have the appearance of a branch of Waterstones or even a shopping mall. But instead, I found a building that is both recognizably a library, but also a place buzzing with life. Here and here are links to a couple of reviews.

With public libraries around the country forced to close because of financial pressure, and repeated declarations that the book is dead since the introduction of the e-book and the internet, it’s a statement of faith in the long-term viability of books. But more importantly, as City Council Deputy Leader Ian Ward declared: “With this amazing building, we have a new image redefining Birmingham as a city of learning, knowledge and the future”.

With public libraries around the country forced to close because of financial pressure, and repeated declarations that the book is dead since the introduction of the e-book and the internet, it’s a statement of faith in the long-term viability of books. But more importantly, as City Council Deputy Leader Ian Ward declared: “With this amazing building, we have a new image redefining Birmingham as a city of learning, knowledge and the future”.

The way in which we all learn has changed enormously over the past few decades, and the Library of Birmingham reflects these changes. It’s a place to borrow books and CDs, but also to enjoy exhibitions, to attend events, to study, to learn new skills and to improve job prospects. But far from being an attack on the traditional role of libraries, these are all functions that Libraries have long aspired to. Andrew Carnegie, the philanthropist who paid for the building of thousands of public libraries, did so in order that poorer people could educate and enlighten themselves. The ancient Library of Alexandria was a centre for study and research, apparently including meeting rooms, lecture halls and even gardens in addition to the thousands of scrolls that made up the Library.

The New Statesman’s report on the Library enthuses “It is bold, it is beautiful, it is barely believable”, and describes the incorporation of stunning new views across the city as “a democratising coup de theatre, giving the city back to its residents”

The New Statesman’s report on the Library enthuses “It is bold, it is beautiful, it is barely believable”, and describes the incorporation of stunning new views across the city as “a democratising coup de theatre, giving the city back to its residents”

The library itself manages to be both spaciously impressive and intimate. In her blog about the library Serena Trowbridge applauds the building’s concentration on learning and culture, but comments: “Of course, the crucial question is what it will be like as a space in which to study, research and write”. I hope this concern will be unfounded: moving away from the busy central rotunda I was pleasantly surprised to find quiet areas where it would be possible to concentrate without too many distractions.

At the core of the building is the Golden Box, two floors hidden from the public in which are kept the Library’s world-class archive and photography collections. I was pleased to see these secure, air-conditioned spaces are located centrally rather than in underground storage areas which are prone to flooding. Being immediately above the archives, Heritage and Photography floor with the Centre for Archival Research also reduces security risks and keeps the distance these items have to be moved to a minimum.

At the core of the building is the Golden Box, two floors hidden from the public in which are kept the Library’s world-class archive and photography collections. I was pleased to see these secure, air-conditioned spaces are located centrally rather than in underground storage areas which are prone to flooding. Being immediately above the archives, Heritage and Photography floor with the Centre for Archival Research also reduces security risks and keeps the distance these items have to be moved to a minimum.

But what about the city’s Shakespeare Library? Birmingham has no direct associations with Shakespeare (one piece about the library rather over-enthusiastically suggested that Shakespeare was a Brummie), but he has been an essential part of the city’s cultural legacy for nearly a hundred and fifty years, affirmed by the creation of the Shakespeare Memorial Library room. Here is its history, taken from the website:

But what about the city’s Shakespeare Library? Birmingham has no direct associations with Shakespeare (one piece about the library rather over-enthusiastically suggested that Shakespeare was a Brummie), but he has been an essential part of the city’s cultural legacy for nearly a hundred and fifty years, affirmed by the creation of the Shakespeare Memorial Library room. Here is its history, taken from the website:

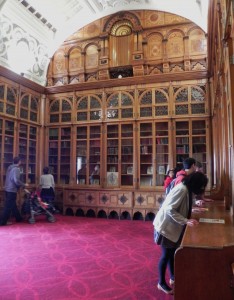

Created and designed to house the Shakespeare Memorial Library by John Henry Chamberlain in1882, a founder member of Our Shakespeare Club. He was responsible for re-building the old Central Library after the original building was gutted by fire in 1879. The Shakespeare Memorial room opened off the new wing of the L shaped reading room of the reference library on the first floor of the building. With the ever rising collection of material the Birmingham Shakespeare Library outgrew this room in 1906.

The room was highly praised and is in an Elizabethan style with carvings, marquetry and metalwork representing birds, flowers and foliage. The woodwork is by Mr. Barfield, a noted woodcarver, the brass and metal work by Hardmans. The ceiling decoration is stenciled.

Controversy surrounded plans to demolish the Central Library in 1971. Anthony Crossland the Environment Minister ruled that the Shakespeare Memorial room must be preserved and be readily accessible to the people of Birmingham… Eventually it was re-built as part of the School of Music complex in 1986.

The Shakespeare Memorial Room is now situated on top of the Library of Birmingham and opened in September 2013.

Here’s a piece by the BBC’s Will Gompertz including a visit to the Shakespeare Memorial Room.

Birmingham’s Shakespeare Collections lacked visibility in the 1970s Central Library. There were Shakespeare books on open shelving, but little to indicate the riches that were held in secure storage. It’s a problem with Special Collections everywhere, though the ability to digitise material helps to open access to these rare, fragile resources. Reinstating the Shakespeare Memorial Library Room gives the collection a focal point.

The New Statesman describes Libraries as “buildings charged with meaning about how a society sees itself and what it values”. I’d love to have seen this room as an integral part of the Library itself, where it could have been a strong reminder of the treasures hidden in the building, but as “the icing on top of the cake” it is still heartening to see the importance of Shakespeare to the cultural life of the city so positively affirmed. In due course I’m looking forward to seeing the Library’s new facilities acting as a springboard to inspire people with a love of Shakespeare by producing more material on the website, creating exhibitions and putting on imaginative events in collaboration with Birmingham Rep.

The New Statesman describes Libraries as “buildings charged with meaning about how a society sees itself and what it values”. I’d love to have seen this room as an integral part of the Library itself, where it could have been a strong reminder of the treasures hidden in the building, but as “the icing on top of the cake” it is still heartening to see the importance of Shakespeare to the cultural life of the city so positively affirmed. In due course I’m looking forward to seeing the Library’s new facilities acting as a springboard to inspire people with a love of Shakespeare by producing more material on the website, creating exhibitions and putting on imaginative events in collaboration with Birmingham Rep.

Just around the time of the design of the Shakespeare Memorial Library in Birmingham the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre was being built in Stratford-upon-Avon. I’ve always been impressed that in the late 1870s this building incorporated a wing with a library on the ground floor, with an inner room for study and a public exhibition area, while upstairs it housed a picture gallery and across the road was a building that included a lecture hall. A truly multi-purpose complex, ahead of its time, designed to stimulate people’s enjoyment and knowledge of Shakespeare, and there in the midst of it all was a library.

“Knowing I lov’d my books, he furnish’d me

From mine own library with volumes that

I prize above my dukedom.”

(The Tempest)