On 15 October it was announced that Rufus Norris was to be appointed to the most important job in UK theatre, as Artistic Director of the National Theatre, taking over in April 2015.

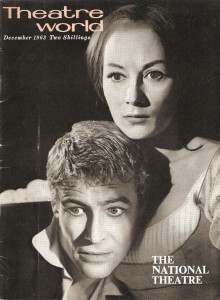

Then next week, on 22nd October the National Theatre celebrates 50 years since its first performance. This was a production of Hamlet, at the Old Vic, directed by Laurence Olivier, with a cast including Peter O’Toole, Rosemary Harris, Michael Redgrave, Diana Wynyard, Frank Finlay, Derek Jacobi and Robert Stephens.

The creation of a National Theatre for the UK had taken many years. It was first suggested in 1848, interestingly just after Shakespeare’s Birthplace was purchased for the nation. It took another thirteen years after the first production for Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre building to be opened by the Queen. The story of the many obstacles that stood in the way, and the eventual creation of the what has become a great national institution has been fully researched by Daniel Rosenthal in the National Theatre’s archives.

He’s unearthed a lot of unpublished material and interviewed all the surviving Artistic Directors and well as many great actors for his new book, The National Theatre Story, being published by Oberon Books in November. The history is also to be celebrated by a three-hour programme, The National Theatre at 50, on Radio 4 Extra on Saturday 19 October (9am- 12, repeated 7pm-10). James Naughtie has also presented two radio documentaries on its history, The Road to the National Theatre.

He’s unearthed a lot of unpublished material and interviewed all the surviving Artistic Directors and well as many great actors for his new book, The National Theatre Story, being published by Oberon Books in November. The history is also to be celebrated by a three-hour programme, The National Theatre at 50, on Radio 4 Extra on Saturday 19 October (9am- 12, repeated 7pm-10). James Naughtie has also presented two radio documentaries on its history, The Road to the National Theatre.

From its very first production Shakespeare was seen as central to the National Theatre. In an interview with Rufus Norris following his appointment, Mark Lawson commented that Shakespeare is a gap in Norris’s experience, having directed only one production. “Will you leave Shakespeare to others?” he asked. Norris affirmed that Shakespeare would be “a very large part of the rep”, and that “Shakespeare is absolutely the bedrock of our literary, let alone our dramatic culture”, but left it open as to whether he would be directing Shakespeare himself.

The link with Shakespeare is a strong one: not only was the first artistic director of the National the greatest Shakespearean actor of his time, the post has also been taken by two former Artistic Directors of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn. And the outgoing Artistic Director, Nicholas Hytner, has had notable successes with Shakespeare, most recently his Othello starring Adrian Lester and Rory Kinnear. Hytner has recently commented, however, that he too has struggled with Shakespeare.

Norris is certainly not giving much away about his plans, and no wonder: he doesn’t take up the reins until April 2015. After his appointment as Artistic Director of the RSC, it took Gregory Doran many months to formulate his first big announcement, which included the production of Richard II which as I write is about to have its press night on 17 October. This production is the first of Doran’s planned cycle of all of Shakespeare’s plays which are to be staged over a period of five or six years. A recent interview with Doran asked him to outline his overriding vision for the RSC.

Excellence, it’s got to be. It all starts with how we do Shakespeare on the main stage; everything else is a pyramid beneath that. We aspire to be the best, we may not always be the best, we may not always get there, but we always strive to be the excellence that Shakespeare deserves.

And asked how he would measure success:

Success would mean there being no question about the RSC’s London base, as well as there being a sense of Stratford being the Shakespeare destination. Those two things are my priority.

There are interesting parallels between the two men. Unlike most of their predecessors in the roles, both are trained actors, and neither are Oxbridge graduates. Both have partners who are heavily involved in theatre: Norris’s wife is playwright Tanya Ronder, and Doran’s partner is one of our greatest actors (who incidentally has done much of his best work at the National Theatre), Antony Sher.

The Theatre World’s reviewer of the 1963 Hamlet found it to be “all that a National Theatre production of Shakespeare’s tragedy should be”. Performed in period costume it was “clear, compelling and unambiguous”, O’Toole was “mercifully lacking in gimmicks and exaggerated histrionics” and the cast “created a timelessness in the characters which brought us closer to them than ever before”. Only two years later, in Stratford, the young Peter Hall was to produce a very different version of the play. Maybe feeling the need to give his company a new and distinctive personality in the face of the National Theatre’s creation, Hall’s production starred the little-known David Warner playing Hamlet as a 1960s student, set against the politically oppressive Establishment. It attracted a whole new generation to Shakespeare and a new following for the fledgling RSC.

Fifty years on, there have been massive changes in almost every part of our lives, but for both national companies Shakespeare is still at the centre of the theatrical landscape of the UK.