The final of the Great British Bake-Off screens on the evening of 8 October. Watching this immensely popular series over the last few weeks I wondered how much Shakespeare knew about how his food was produced, and whether he ever prepared food himself. Shakespeare has been reckoned to be a soldier, sailor, lawyer and many other professions, but never a cook or baker.

The final of the Great British Bake-Off screens on the evening of 8 October. Watching this immensely popular series over the last few weeks I wondered how much Shakespeare knew about how his food was produced, and whether he ever prepared food himself. Shakespeare has been reckoned to be a soldier, sailor, lawyer and many other professions, but never a cook or baker.

Yet in Troilus and Cressida he shows he understands all the stages of baking, Pandarus comparing it with the stages of courtship, both of which require patience.

Pandarus: He that will have a cake out of the wheat must needs tarry the grinding.

Troilus: Have I not tarried?

Pandarus: Ay, the grinding; but you must tarry the bolting.

Troilus: Have I not tarried?

Pandarus: Ay, the bolting, but you must tarry the leavening.

Troilus: Still have I tarried.

Pandarus: Ay, to the leavening’ but here’s yet in the word “hereafter” the kneading, the making of the cake, the heating of the oven and the baking; nay, you must stay the cooling too, or you may chance to burn your lips.

He shows too that he knows the sort of ingredients that are used to make food for a feast in The Winter’s Tale.

Let me see; what am I to buy for our sheep-shearing feast? Three pound of sugar, five pound of currants, rice….I must have saffron to colour the warden pies; mace; dates…nutmegs, seven; a race or two of ginger, but that I may beg; four pound of prunes, and as many of raisins o’ the sun.

For Shakespeare, cakes seem to be associated with the more unsophisticated characters in his plays. It’s Touchstone in As You Like It and the Clown in All’s Well who talk about pancakes, Doll Tearsheet who tells us that Pistol lives on “mouldy stew’d prunes and dried cakes”, Pistol who mentions “wafer-cakes”, and Dromio of Ephesus talks about cakes in The Comedy of Errors. Hugh Otecake and Alice Shortcake are mentioned by comic characters in Much Ado About Nothing and The Merry Wives of Windsor respectively. Almost the only reference to cakes from someone higher up the social scale is Sir Toby Belch’s famous attack on Malvolio: “Dost thou think, because thou art Virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?”

Maybe this is because cakes tended to be associated with celebrations marking particular moments in the farming year. I’ve recently been reading P W Hammond’s Food and Feast in Medieval England which explains that at the end of ploughing it was traditional for seed cake to be served, for instance. Cake is never an essential part of the diet, but even now it cheers people up and the Bake-Off is a great restorative at a time when the news is full of gloom.

So what sort of sweet things might Shakespeare have known? We’re familiar with the idea that ingredients were very different in Shakespeare’s day. Honey was used for sweetening more than sugar, there was no coffee or chocolate, and fruits were strictly seasonal. Raising agents used in cakes, (other than yeast) were only invented in the mid-nineteenth century. But many familiar cake ingredients were available: cream, butter, eggs, flour, dried fruit, even exotic spices.

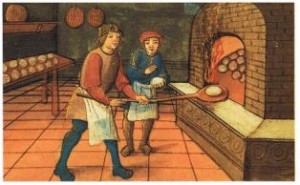

Hammond’s book tells a depressing story of the diet of most people in the fifteenth century. Not only was the choice of ingredients restricted, so was the method of cooking the food. Five acres of ground would produce enough grain for a family. Ideally most of it would be made into bread, but “Possession of an oven was rare (judging by archaeological evidence), and those without ovens probably asked neighbours or used the communal oven. It has been suggested, in fact, that, except in the south of England, the consumption of bread was rare and that cereals were eaten as the staple diet chiefly in the form of porridge and broths.” Not much chance of cake here, then, and even if progress was made by Shakespeare’s time there must have been many people for whom access to an oven was rare.

Without an oven cooking was restricted to pots over an open fire, so cakes as we know them would be off the menu, though pancakes and griddle cakes would have relieved the monotony. In any case ovens were difficult. They were usually insulated metal boxes, designed to keep heat in. First the oven would be heated up by burning twigs inside it, then when hot enough they would be raked out and the bread went in. The oven was sealed and the bread would be left to cook as the oven cooled down.

I once took part in a food festival in which we prepared some Elizabethan food (this is now done regularly at Mary Arden’s Farm, see their facebook page). My contributions included these Fine Jumbals, adapted from Lorna Sass’s book To The Queen’s Taste. I remember them being very good.

Fine Jumbals

Half a cup of sugar

2 egg whites

1 egg yolk

1 cup sifted flour

4 tablespoons cooled melted butter

1 and a half teaspoons rose water

Three quarters of a cup of ground almonds

A few drops almond essence

Aniseeds, or ground coriander seeds

Whisk the sugar and egg whites until thick. Add the egg yolk, flour, butter and rose water and mix well. Add almonds and essence. The mixture should be quite thick, thicker than a cake mix. Put teaspoonfuls of the mixture onto greased baking sheets, leaving room for spreading. Sprinkle with seeds and back at 375 degrees for 12-15 minutes until brown and the edges. Remove from sheets while hot.

More recipes for sweet Elizabethan treats are given on the Ugborough history group’s website.